The Biden administration made a huge announcement regarding student loans on Wednesday (August 24th). An announcement was expected given the upcoming expiration of the moratorium on student loan payments. The moratorium was originally part of the CARES Act, as part of income relief, and set to expire in September 2020 – but it was extended several times after that, first by President Trump and then by President Biden.

President Biden extended the moratorium once again, to December 31st, 2022, but the overall scale of changes was a surprise. In addition to extending the payment freeze, there were two other big pieces –

- Student loan debt forgiveness up to $10,000 per borrower with incomes less than $125,000 ($250,00 for couples). For those who received Pell Grants, the canceled amount can go up to $20,000. This applies to only federal student loans (which make up about 90% of outstanding student loan debt) and importantly, the canceled amounts will not be taxed.

- A new Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plan with better terms for low- and middle-income borrowers. This is the part that really matters going forward. Like existing IDRs, payments are calculated based on earnings and adjusted every year. The difference is that the new plan will reduce undergraduate loans to 5% of discretionary income (down from 10-15% in existing plans). More low-income workers, i.e. those earning under 225% of the poverty level, will qualify for zero-dollar payments. Borrowers with loan balances below $12,000 will make monthly payments for 10 years before cancellation. For all others, they will have to make monthly payments for 20 years before cancelation (like current IDRs). Crucially, unlike existing IBRs, loan balances will not grow as long as the monthly payment is made – even if the payment level drops with income.

A tax cut?

A good way to think about student loan payments is as a tax. The tax in this case being the cost of servicing the debt. So freezing student loan payments or reducing/removing them altogether (by forgiving the principal amount) is a tax cut, freeing up money that would normally go toward servicing the debt.

An important point here is that debt forgiveness cuts the long-term liability, but that is not equivalent to getting a $10,000 (or $20,000) check in the mail that can be spent immediately. The money that can be spent immediately are the monthly payments that go toward servicing the student loan, which would now go away (or be reduced).

All else equal, tax cuts tend to increase demand, which could be inflationary if supply cannot meet that extra demand.

Take for example the $2,000 cap on Medicare Part D out-of-pocket spending that will go into effect in 2025 as part of the Inflation Reduction Act. In 2020, Part D enrollees who did not have subsidies spent an average of $6,200 (out-of-pocket) on the cancer drug Revlimid. The $2,000 cap means they would now have an extra $4,200. The cap is basically a tax cut that puts more money in seniors’ pockets, potentially offsetting some of the deflationary impact from having the government negotiate Medicare drug prices. In this example, if seniors go out and spent the extra $4,200 on a used vehicle, prices for used vehicles would increase (assuming there was still a shortage).

The wrinkle in the student loan situation is that there was already a freeze on student loan payments, and that just got extended through year-end.

In other words, the “tax cut” was already in place, and there is no additional tax cut that will cause more spending/inflation than there is now. In fact, the end of the freeze in December means for those borrowers still holding student loans, they will see a “tax increase” in January 2023 – as they must start servicing student loan debt once again. Tax increases are generally a drag on growth, and potentially deflationary.

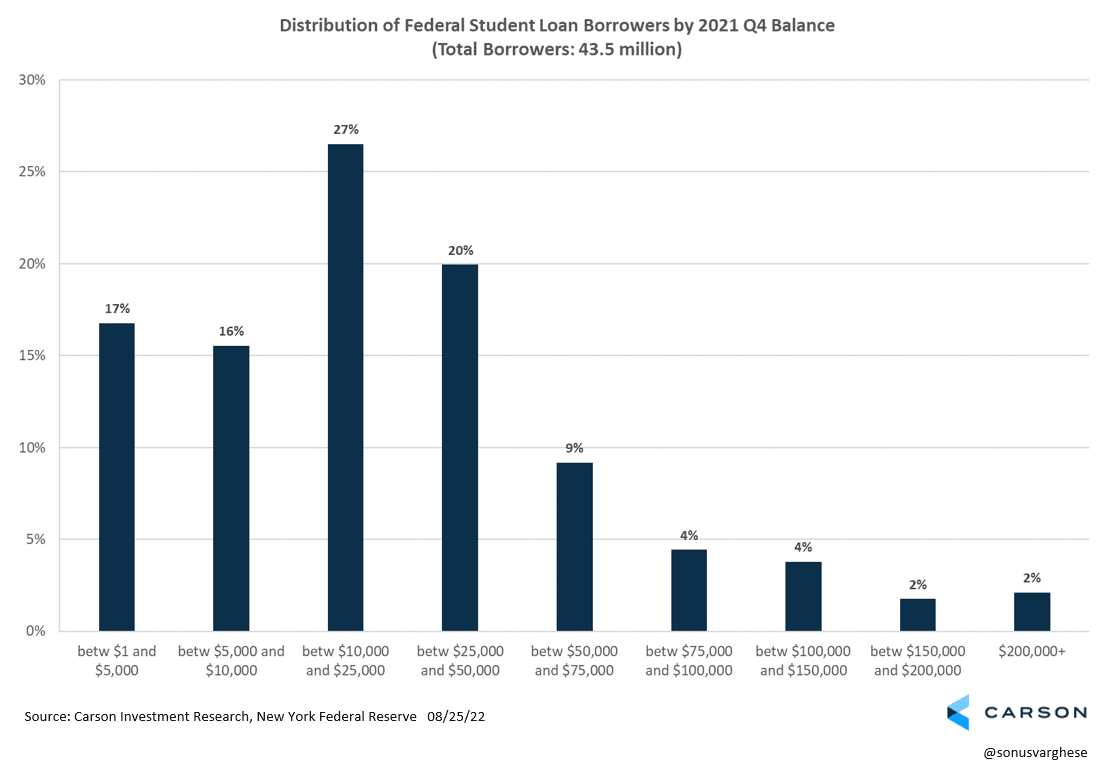

Of course, many borrowers will have no payments to make, or lower payments than they would have had without cancellation. Out of approximately 43.5 million borrowers, about a third of them had balances below $10,000 as of 2021 Q4. Another 27% had balances between $10,000 and $25,000.

So the deflationary impulse is going to be lower than it would have been if there was no debt forgiveness and all borrowers had to restart payments.

How much of an impact will this have immediately?

We’re talking small numbers with respect to US GDP. Most commentary tends to focus on the overall size of the student loan debt overhang, which is about $1.6 trillion. But what really matters for the economy, and consumption, is how much is being paid to service the debt.

Prior to the pandemic-related moratorium, the US government collected $70 billion in student loan payments (in 2019). That translates to about 0.3% of GDP, though obviously the entire $70 billion is not going to zero. Roughly, only about half that amount. But that should give you an idea of the potential aggregate income boost to households.

Analysts at Goldman Sachs estimate that the aggregate impact from such an income boost would be small, with the level of GDP rising by about 0.1% in 2023 and smaller effects in future years. And the impact on inflation is expected to be similarly small.

For perspective, the Bureau of Economic Analysis just revised higher second quarter GDP growth by almost 0.1%. Which is to say the estimated short-run impact of student loan cancellation on economic growth is within the realm of noise.

What about longer-term impact?

Let’s separate this section into two parts – what it means for borrowers and what it means for the lender, i.e. the federal government.

For borrowers, debt forgiveness means their personal balance sheet improves. In other words, it increases their net wealth (though a lot of these loans may never have been repaid fully anyway). Typically increases in net wealth are not spent over the short-term but over the course of several years.

Where this is likely to make a real difference is an improved ability to borrow, with improved terms on any new loans that are taken out. For example, instead of paying 8% on a personal loan, they may be able to get terms for 6%. Having better access to credit may improve the odds of starting small businesses and even support new household formation. It may also improve access to rentals, with landlords a little less concerned about a renters’ ability to make payments. In aggregate, cancellation is positive for borrowers, and positive for private lenders as well. Over the long-term, this could potentially increase demand for housing – as payments that would have gone to servicing student loan debt goes toward saving for a down payment.

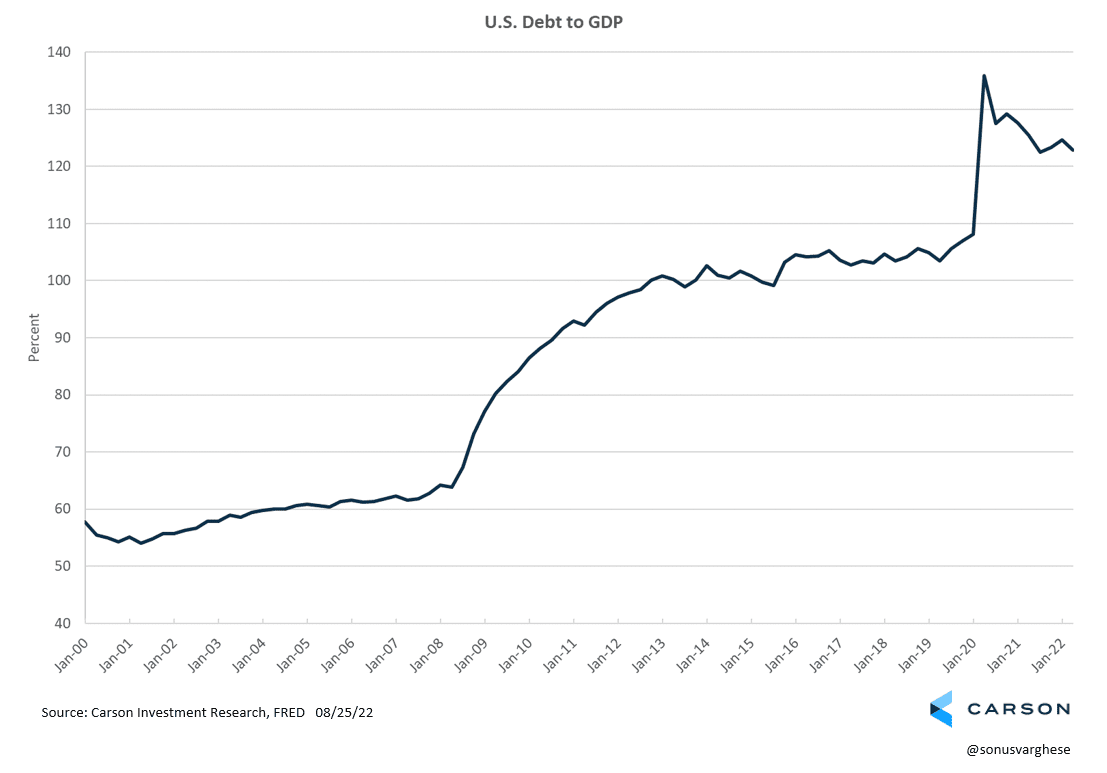

For the federal government, the total cost of cancellation is estimated to be around $400 billion, equivalent to about 1.6% of GDP. But nominal GDP growth has been rising recently (amid inflation), and so debt-to-GDP has been rapidly falling – from 136% in Q2 2020 to 123% as of Q2 2022.

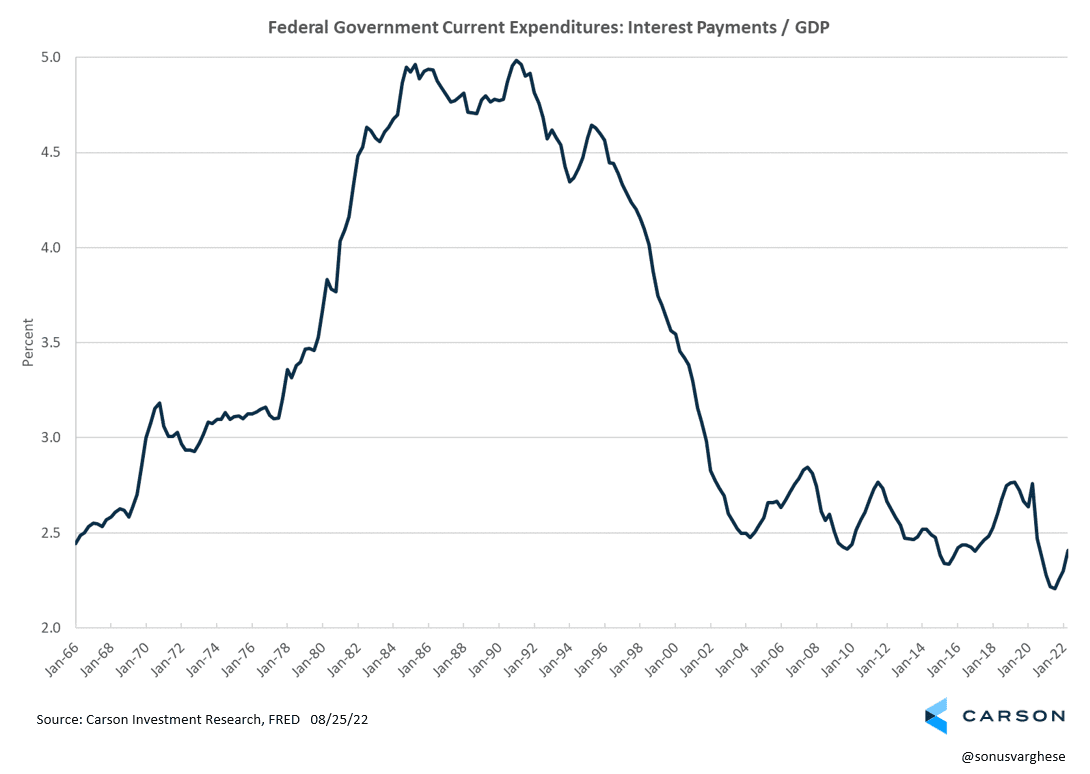

More importantly, the fact that nominal growth is rising a lot faster than interest rates – nominal GDP rose at an annualized pace of 7.5% over the first half of 2022 – means that the governments’ cost of servicing its debt remains close to 50-year lows (2.4% of GDP as of Q2 2022).

In summary, we don’t believe student loan cancellation will have a significant impact on economic growth and inflation – both in the near-term and long-term.