2022

State of Women in Wealth Management Report

Representation Matters.

About the 2022 State of Women in Wealth Management Report

In 2022, Carson Group commissioned a research study investigating the experiences and perceptions of both women and men on the opportunities and challenges faced by female advisors in the financial services industry. The intent is to conduct this study annually, tracking year-over-year changes in the experience of women in wealth management – financial advisors, operations leaders and firm owners – as well as the perceptions of that experience by women and men alike.

Currently women make up more than half of the U.S. population, but less than a quarter of financial advisors.

The Certified Financial Planning Board of Standards

reports that only 23.5% of Certified Financial Planning® professionals are women, a number that has stayed flat since the first study in 2013.1

According to Barron’s

In the broader world of financial advice, only 15-20% of advisors are women.2

The American College of Financial Services

finds that only one-third of advice firms surveyed had women in client-facing roles (while 88% had women in administrative or operations roles).3

The objective of the study is to identify insights that can lead to actionable solutions to increase both the representation and success of female advisors.

Representation Matters.

About the 2022 State of Women in Wealth Management Report

In 2022, Carson Group commissioned a research study investigating the experiences and perceptions of both women and men on the opportunities and challenges faced by female advisors in the financial services industry. The intent is to conduct this study annually, tracking year-over-year changes in the experience of women in wealth management – financial advisors, operations leaders and firm owners – as well as the perceptions of that experience by women and men alike.

Currently women make up more than half of the U.S. population, but less than a quarter of financial advisors.

The Certified Financial Planning Board of Standards

reports that only 23.5% of Certified Financial Planning® professionals are women, a number that has stayed flat since the first study in 2013.1

According to Barron’s

In the broader world of financial advice, only 15-20% of advisors are women.2

The American College of Financial Services

finds that only one-third of advice firms surveyed had women in client-facing roles (while 88% had women in administrative or operations roles).3

The objective of the study is to identify insights that can lead to actionable solutions to increase both the representation and success of female advisors.

Carson’s Role

Carson believes that the financial advisors transforming families and communities by helping grow and protect their wealth should look more like the populations they’re serving.

Carson is committed to moving the needle on representation in the industry by:

Building a problem solving community

of women and male allies who are committed to creating firm cultures where women thrive

Identifying barriers

to women joining and staying in financial planning

Recruit more women

into our profession

Support career paths

for women in non-advisory roles into leadership or financial advisor roles

Make our profession worthy

of the women we’re recruiting

Carson’s Role

Carson believes that the financial advisors helping transform our communities by helping families

grow and protect their wealth should look more like the populations they’re serving.

Carson is committed to moving the needle on representation in the industry by:

Building a problem solving community

of women and male allies who are committed to creating firm cultures where women thrive

Identifying barriers

to women joining and staying in financial planning

Support career paths

for women in non-advisory roles into leadership or financial advisor roles

Recruit more women

into our profession

Make our profession worthy

of the women we’re recruiting

This report is one part of Carson’s larger initiative toward greater representation of women within the industry, focusing on identifying the key barriers to women entering and thriving in the financial advice profession.

Contents

Section 1

Study Methodology

Section 2

Perceived Barriers

Section 3

Choosing a Financial Advice Career

Section 4

Advancement of Women in Financial Advice Careers

Section 5

Finding and Working with Clients

Section 6

Differing Opinions

Section 7

Current and Proposed Solutions

Executive Summary

Findings are based on a survey of

335

financial advice professionals

Findings are based on a survey of

335

financial advice professionals

Respondents indicated:

The industry is currently ineffective at recruiting women into the financial advice profession.

Women in wealth management experience different barriers than men.

Caregiving obligations were the most significant barrier, followed by difficulty finding a firm that was a culture fit.

Men are markedly more optimistic about the effectiveness of recruitment and retention efforts, current leadership representation of women, and the presence of gender-based discrimination.

Gender-based discrimination comes into play in how clients choose advisors and how advisors choose other advisors for joint work.

Men are slightly more likely to report prospecting for new clients as a primary barrier to success. Female responses show prospecting being less of a barrier as they become more experienced.

Nearly three quarters of respondents have women represented in the leadership of their firms.

Gender was not the determining factor in whether a respondent believed there was equal access to prospecting opportunities – compensation model was. More AUM advisors saw an even playing field than other models, with salaried employees reporting the most uneven conditions.

In the interviews, women often discussed “bad behavior” by men, particularly at industry conferences, as a reason women don’t enter or stay in the profession.

Virtually every recommendation to improve the representation of women in wealth management revolved around retention – what firms should do to keep and grow their existing employees, rather than recruitment.

1Flexibility

2Training and education support

3Mentorship

4More women to leadership

5Clear career paths

6Zero tolerance policies on discrimination, harassment and assault

Section 1

Study Methodology

This study is a combination of a quantitative survey with some open-ended feedback questions and a series of qualitative interviews.

The survey sample was developed via self-selection through organic social media posts, email marketing, and digital ads targeted specifically to financial advice professionals. Survey responses were collected using Survey Monkey. Data regression analysis was performed by Michael Norton, PhD.

The interviewees were volunteers from the survey sample. Interviews were conducted, coded and analyzed by Melinda Hubbard, DBA, MBA.

In exchange for participation in the study, Carson donated to Rock the Street Wall Street, a financial and investment literacy program designed to bring both gender and racial equity to the financial markets and spark the interest of high school girls in finance careers. For each survey participant, Carson donated $5. For each interview participant, Carson donated $30. Carson then matched the funds for a total donation of $5,000 for a scholarship at Rock the Street Wall Street.

This study is a combination of a quantitative survey with some open-ended feedback questions and a series of qualitative interviews.

The survey sample was developed via self-selection through organic social media posts, email marketing, and digital ads targeted specifically to financial advice professionals. Survey responses were collected using Survey Monkey. Data regression analysis was performed by Michael Norton, PhD.

The interviewees were volunteers from the survey sample. Interviews were conducted, coded and analyzed by Melinda Hubbard, DBA, MBA.

In exchange for participation in the study, Rock the Street Wall Street, a financial and investment literacy program designed to bring both gender and racial equity to the financial markets and spark the interest of high school girls in finance careers. For each survey participant, Carson donated $5. For each interview participant, Carson donated $30. Carson then matched the funds for a total donation of $5,000 for a scholarship at Rock the Street Wall Street.

Section 2

Perceived Barriers

Once a woman starts a career in the field of wealth management, she faces many of the same challenges as her male counterparts – growing a book of business from nothing, operational efficiency, and dealing with the emotional highs and lows of client responses to the market are par for the course.

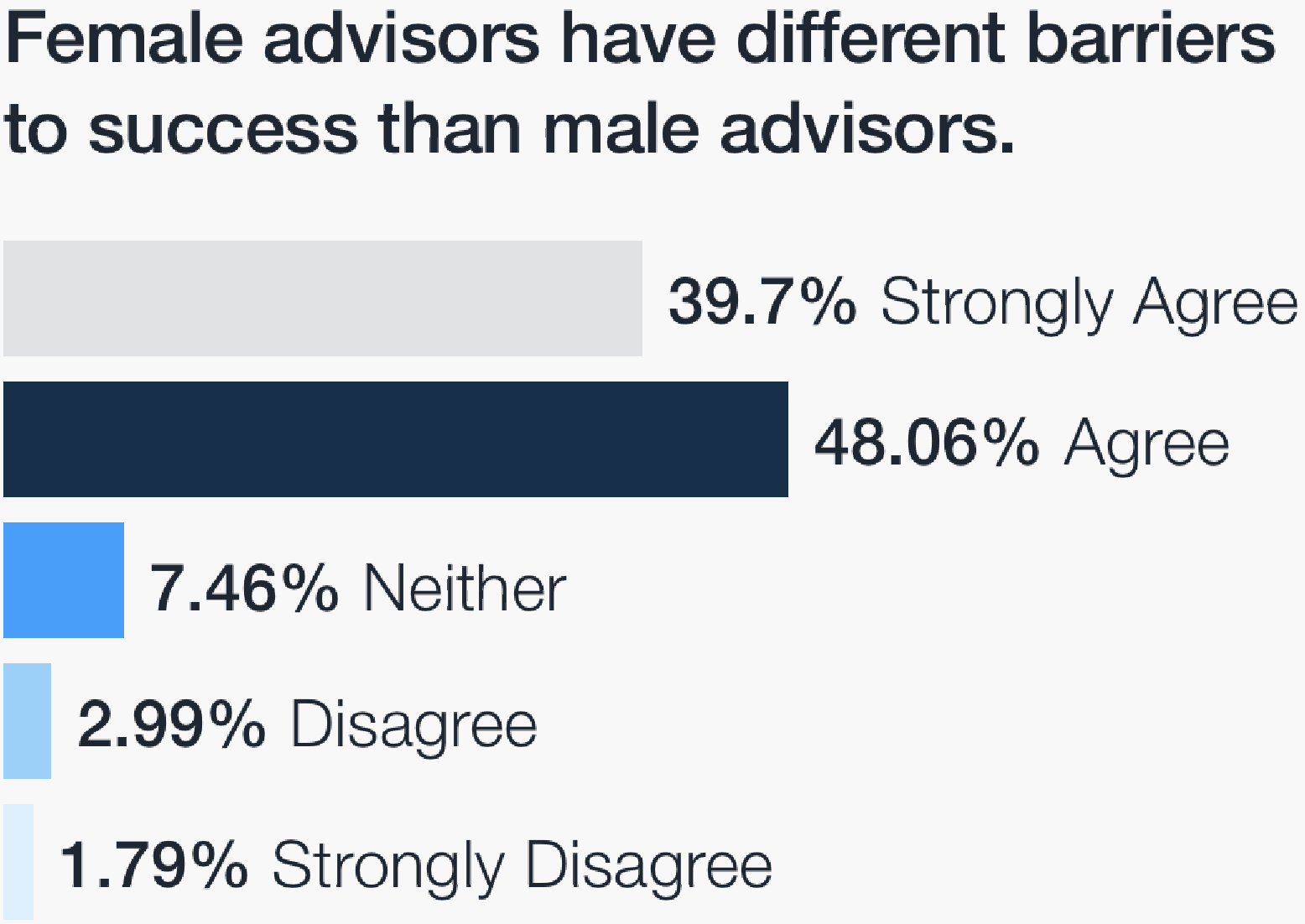

Survey respondents indicated, however, that women in wealth management have additional barriers that men are less likely to deal with. In fact, 87.76% of survey respondents agreed with the statement: “Female advisors have different barriers to success than male advisors,” with only 4.78% disagreeing. While male respondents were somewhat less likely to agree with this statement (81.4% vs. 90.3%), a significant majority acknowledge the presence of unique barriers the same way their female counterparts do.

Once a woman starts a career in the field of wealth management, she faces many of the same challenges as her male counterparts – growing a book of business from nothing, operational efficiency, and dealing with the emotional highs and lows of client responses to the market are par for the course.

Survey respondents indicated, however, that women in wealth management have additional barriers that men are less likely to deal with. In fact, 87.76% of survey respondents agreed with the statement: “Female advisors have different barriers to success than male advisors,” with only 4.78% disagreeing. While male respondents were somewhat less likely to agree with this statement (81.4% vs. 90.3%), a significant majority acknowledge the presence of unique barriers the same way their female counterparts do.

Primary Barriers

The survey asked respondents what barriers female advisors face, giving them four choices and the options to add their own. As one respondent noted, these barriers can apply to men and women, though both men and women who responded acknowledge that these are more likely to be barriers faced by women. The choices provided to respondents are shown at left.Primary Barriers

The survey asked respondents what barriers female advisors face, giving them four choices and the options to add their own. As one respondent noted, these barriers can apply to men and women, though both men and women who responded acknowledge that these are more likely to be barriers faced by women. The choices provided to respondents were:“Gender and age discrimination run rampant in our industry.” – Survey Respondent

Of the write-in barriers received, 47% indicated that gender-based discrimination was a primary barrier. This write-in option received three times as many mentions as the next most frequently named barrier, male-focused social networks – or what multiple respondents referred to as the “Old Boys Club.” Survey designers opted not to include discrimination/sexism as a proposed choice in the desire to not lead participants. The significant write-in number, however, indicates that respondents view sexism in the workplace a significant issue in wealth management.

The “Second Shift” Outside the Office

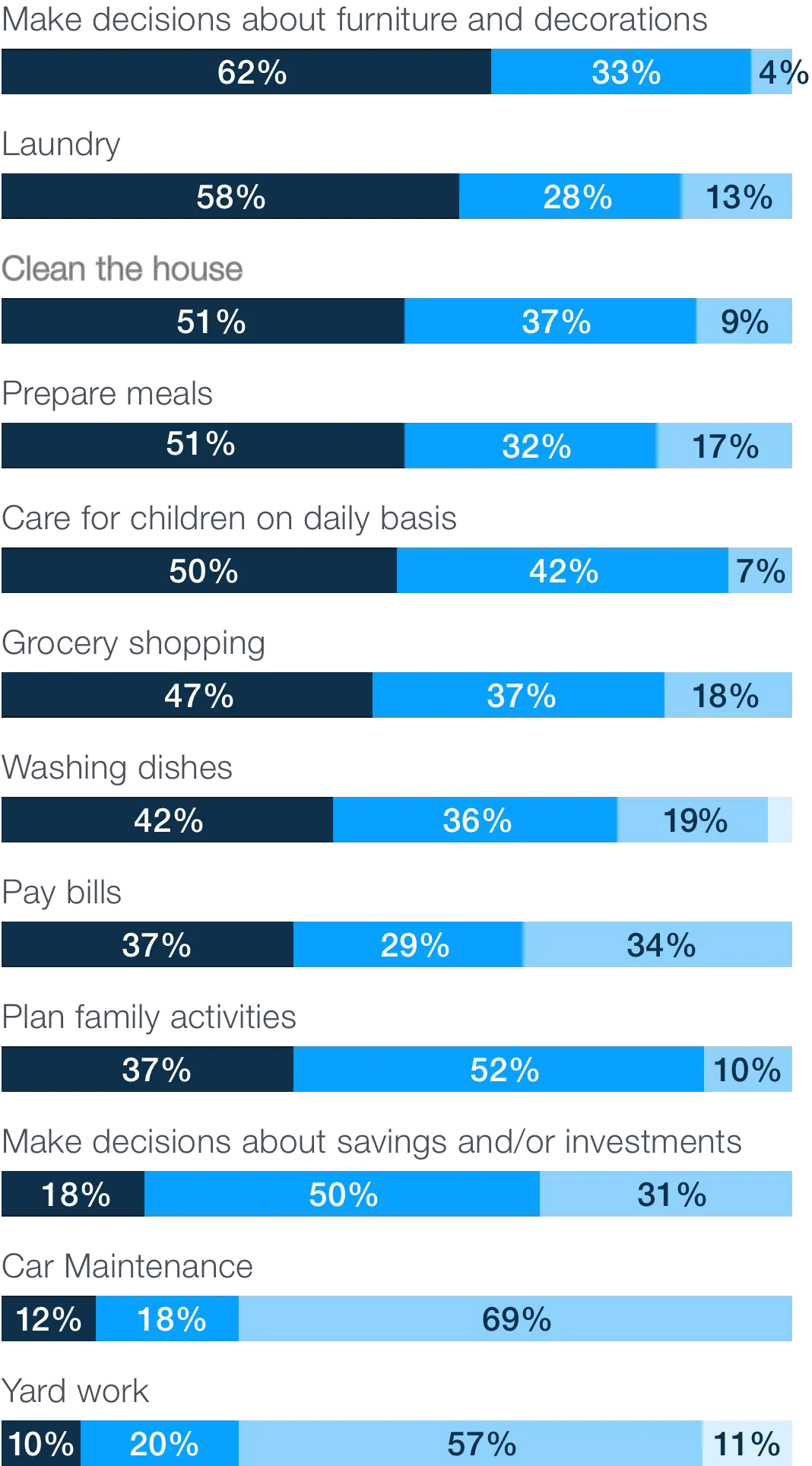

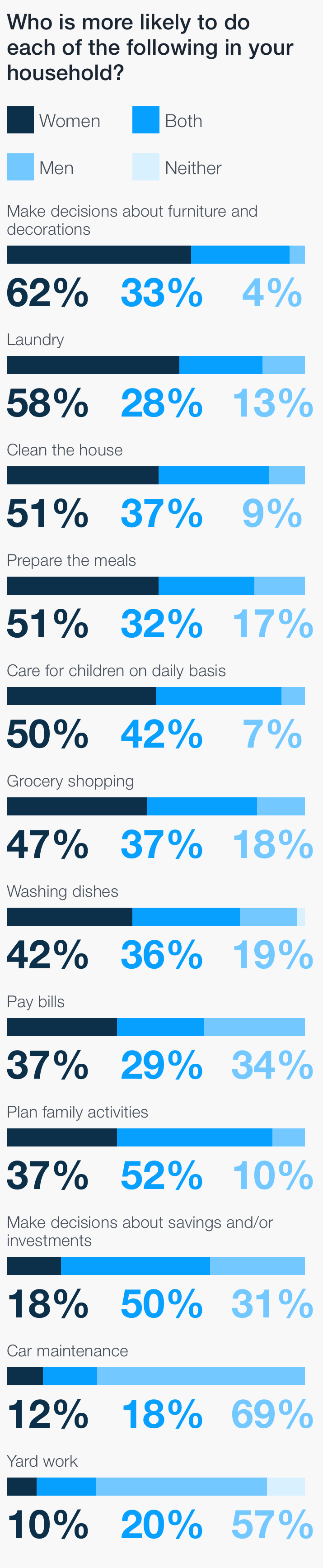

The most identified barrier respondents listed was “Balancing professional role with caregiving obligations,” with 72.75% of respondents selecting this barrier. While societal norms have evolved over the past decade, respondents still perceive caregiving, typically for children but sometimes for aging parents, as a barrier to career success.

Beyond this survey, other contemporary research confirms these perceptions. Gallup’s most recent polling on the topic shows that while distribution of caregiving and household management tasks has equalized some in dual-earner households since 1996, women still carry the lion’s share of these tasks. The difference in childcare duties is particularly marked – with women taking the lead in 50% of households, compared to the 7% of households where men take the lead; 42% of households report an equal split in childcare.

Survey respondents indicated that within the general population, the tasks that male partners routinely take the lead on at home are car maintenance, yard work and investment decisions (though it is logical to assume that in a survey cohort of female financial advisors, she would take on more of this last task). These tasks generally require less frequent attention than those that women are still largely responsible for:

Typical Tasks

Women are Largely

Responsible For

Unsurprisingly, this “second shift” for women has the potential to limit income opportunities and outside-of-work-hours achievement opportunities. One respondent summed it up by saying these obligations were a barrier because, “I don’t have a wife to come work for me.”

Of the write-in barriers received, 47% indicated that gender-based discrimination was primary barrier.

47% indicated that gender-based discrimination was primary barrier.

Who is more likely to do each of the following in your household?

Roles of Men and Women in U.S. Households

The at-home workload is likely why female advisors rate flexibility as the number one benefit their firms can provide. Most respondents (63.88%) believe that a career as a financial advisor is generally conducive to a “work-life” balance, though men are somewhat more likely to hold this belief (72.1% vs 61.6%).4

Culture Matters

The second-most common barrier for respondents was “Difficulty in finding a firm that’s a ‘culture fit’” – 69.76% of respondents considered this a primary barrier. It underscores the importance of firm culture as a critical factor in the success and fulfillment of all advisors, male and female.

The second most common respondent-generated barrier for female advisors was unequal access to social networks, both within the firm and in the community. Several respondents referred to this as the “Old Boys Club,” which is generally defined as the loose social ties and interest-based connections shared by men, but not typically shared by women in the same profession. A 2021 study from Harvard University found that within corporate structure, these informal networks still exert a meaningful influence on the career advancement of women.5

There’s good news here: Though the most common barriers are easily identifiable, female advisors trust firm leadership enough to share their concerns about these barriers: 66.27% of respondents said they feel comfortable sharing obstacles to success with firm leadership.

Section 3

Choosing a Financial Advice Career

Increasing the number of women in wealth management is advantageous for multiple reasons – but the economic advantages alone are compelling. According to consulting company McKinsey & Company, by 2030, American women will control $30 trillion. And 70% of women seeking a financial advisor would prefer to work with a female, according to a study conducted by the Insured Retirement Institute in 2013. That’s a lot of money for firms to leave on the table by not addressing underrepresentation in the next eight years.

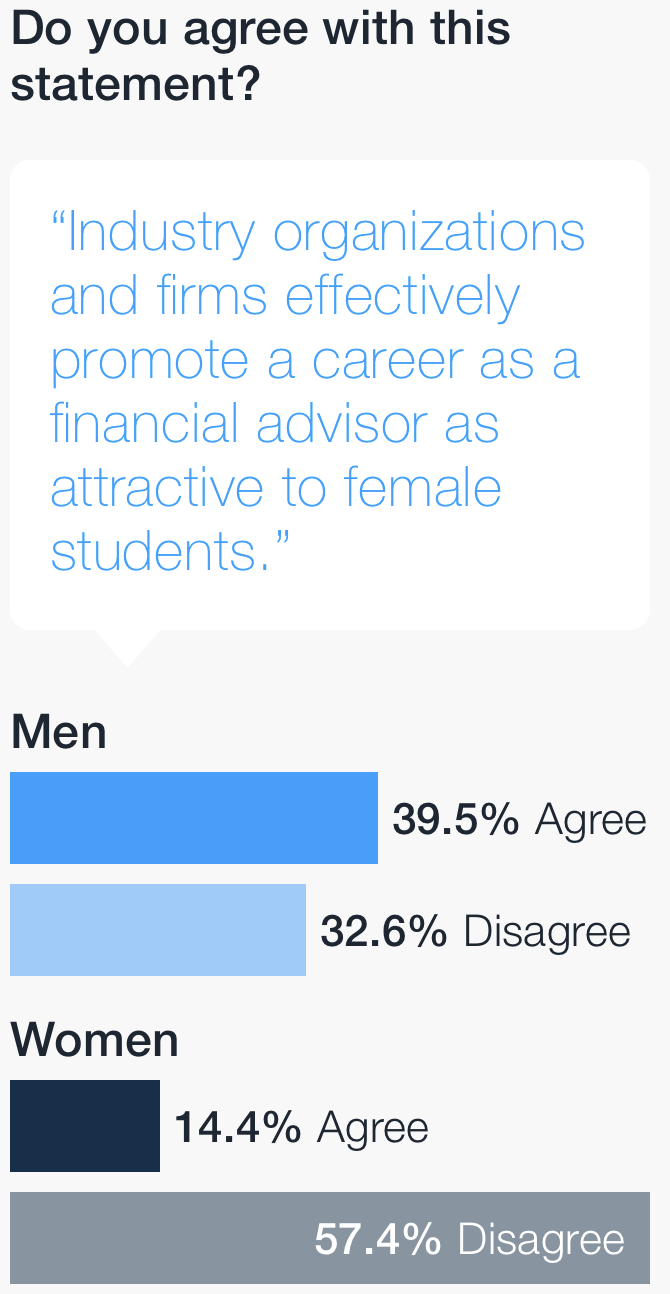

To add women to the industry, recruitment often becomes the focus of change efforts. The survey asked respondents how well they believe the industry is at attracting female students into financial advice as a profession.

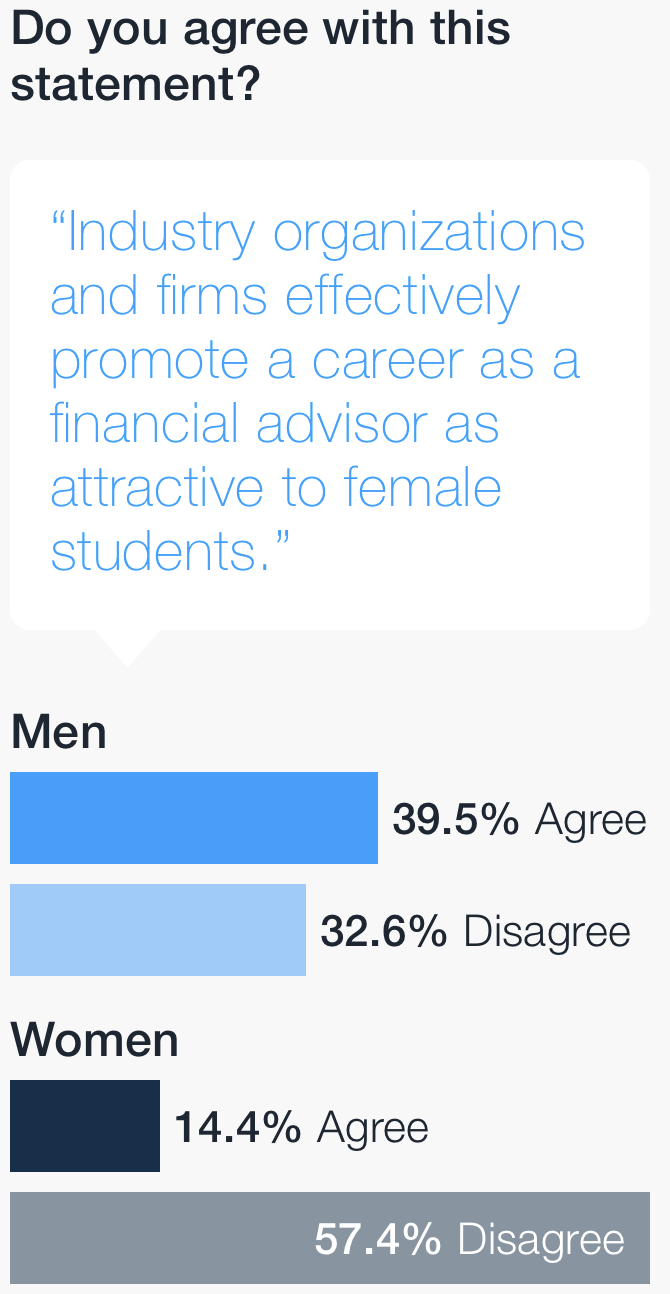

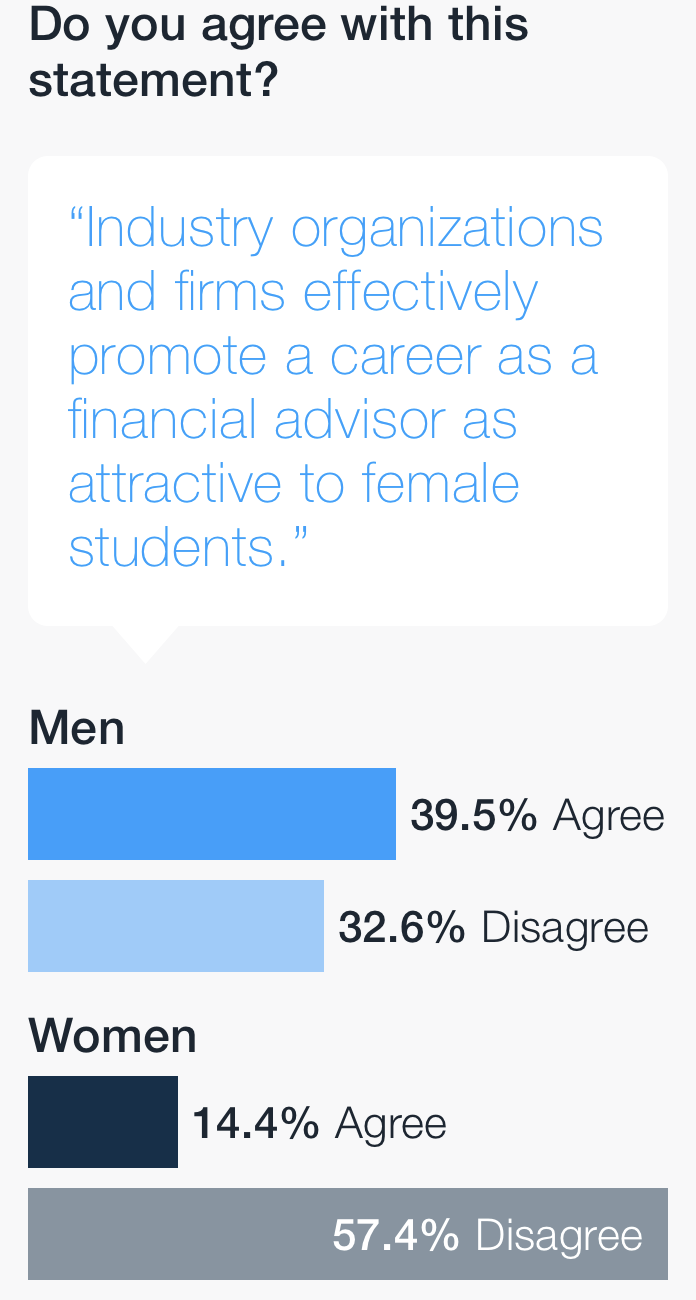

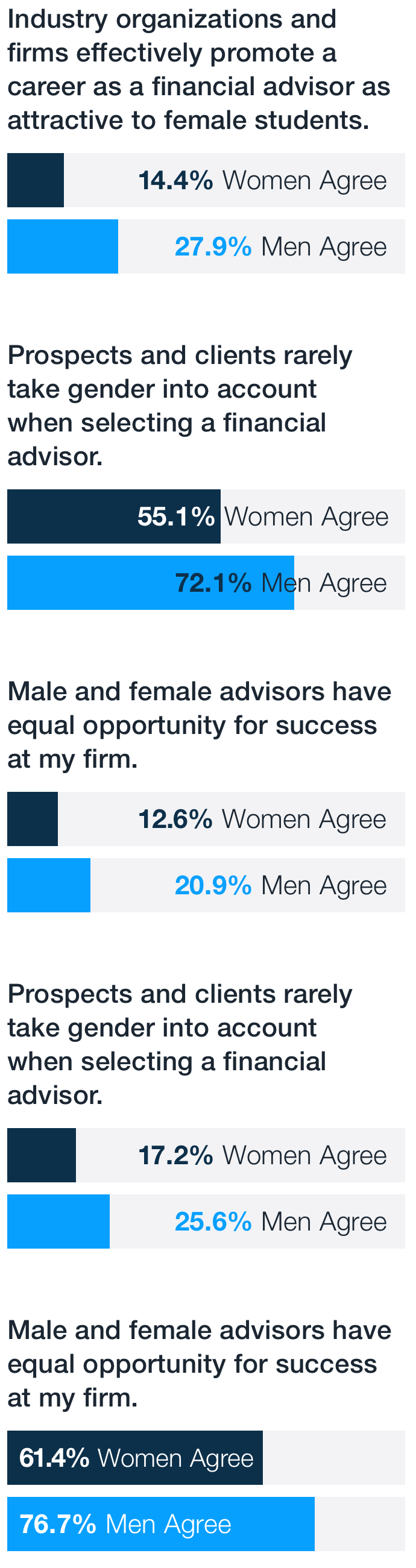

Only 16.42% of respondents agreed with this statement: “Industry organizations and firms effectively promote a career as a financial advisor as attractive to female students.” 52.84% of respondents flatly disagreed with the statement, indicating an industry-wide self-awareness that the profession does a poor job promoting itself to new entrants – particularly young women.

Women, however, were significantly more pessimistic than men, with 57% strongly disagreeing or disagreeing with the statement above, as opposed to 39% of male respondents.

The factors that students use to determine the right career for them are multi-faceted. They often involve the input of family and friends, professors and guidance counselors. As students gain exposure to the industry through their undergraduate curriculum and as career counseling offices become more familiar with the role of financial advisor, the role of “marketing the profession” could fall more on higher education institutions.

An indication of how ineffective the industry and educational institutions are at marketing wealth management as a career choice came from the interviews. Virtually every woman interviewed came to the profession via an indirect route once their careers had already started. Many were brought in by their fathers or other relative, or were in adjacent professions such as banking.

As career decisions are based less on the traditional “word of mouth” awareness that dominated the industry in the past, it may be necessary to shift thinking from attendance at career fairs to more about how the industry can build strong relationships with the financial planning program heads and professors who are training the next generation of financial planners.

Making students aware of the benefits of the profession before college is particularly relevant. After all, if a student is unaware the financial planning/wealth management profession exists, she’s unlikely to construct her major around the requisite skills for success for the role. Even the notion that outstanding financial planners and wealth managers must obtain a degree in a finance-based field presents a problem, as many students who want a career in a helping profession often gravitate toward psychology, social work or education.

The factors that students use to determine the right career for them are multi-faceted. They often involve the input of family and friends, professors and guidance counselors.

Many of the women interviewed were attracted to the profession after seeing what a profound impact it could have on lives.

I was purely an administrative assistant. Once, I was invited by my boss into a client meeting with a man who had laid tile his whole life. But he and his wife saved, and he lived well below his means and he was going to be okay financially. This man did not see himself that way. He really saw himself as much less successful. As my boss is presenting this plan saying, “Not only are you going to be fine, you can do whatever you want to, within reason. You can live the retirement you want to live, you can give to the kids. You can leave a legacy.” And this man starts crying. Which there’s no chance my boss could have predicted that. He couldn’t have orchestrated that if he had wanted to. It just happened to work out that I was in that meeting. I was sold on the career for life.

Most women in financial advice shared in interviews that they love to help their friends and other people, how they love personal finance, and find this industry to be a great fit. They see this industry as a “positive industry where you get to make a positive impact on other people’s lives.” These talking points about transforming lives and helping people are not clearly articulated to potential entrants to the profession.

Section 3

Choosing a Financial Advice Career

Increasing the number of women in wealth management is advantageous for multiple reasons – but the economic advantages alone are compelling. According to consulting company McKinsey & Company, by 2030, American women will control $30 trillion. And 70% of women seeking a financial advisor would prefer to work with a female, according to a study conducted by the Insured Retirement Institute in 2013. That’s a lot of money for firms to leave on the table by not addressing underrepresentation in the next eight years.

To add women to the industry, recruitment often becomes the focus of change efforts. The survey asked respondents how well they believe the industry is at attracting female students into financial advice as a profession.

Only 16.42% of respondents agreed with this statement: “Industry organizations and firms effectively promote a career as a financial advisor as attractive to female students.” 52.84% of respondents flatly disagreed with the statement, indicating an industry-wide self-awareness that the profession does a poor job promoting itself to new entrants – particularly young women.

Women, however, were significantly more pessimistic than men, with 57% strongly disagreeing or disagreeing with the statement above, as opposed to 39% of male respondents.

The factors that students use to determine the right career for them are multi-faceted. They often involve the input of family and friends, professors and guidance counselors. As students gain exposure to the industry through their undergraduate curriculum and as career counseling offices become more familiar with the role of financial advisor, the role of “marketing the profession” could fall more on higher education institutions.

An indication of how ineffective the industry and educational institutions are at marketing wealth management as a career choice came from the interviews. Virtually every woman interviewed came to the profession via an indirect route once their careers had already started. Many were brought in by their fathers or other relative, or were in adjacent professions such as banking.

As career decisions are based less on the traditional “word of mouth” awareness that dominated the industry in the past, it may be necessary to shift thinking from attendance at career fairs to more about how the industry can build strong relationships with the financial planning program heads and professors who are training the next generation of financial planners.

Making students aware of the benefits of the profession before college is particularly relevant. After all, if a student is unaware the financial planning/wealth management profession exists, she’s unlikely to construct her major around the requisite skills for success for the role. Even the notion that outstanding financial planners and wealth managers must obtain a degree in a finance-based field presents a problem, as many students who want a career in a helping profession often gravitate toward psychology, social work or education.

The factors that students use to determine the right career for them are multi-faceted. They often involve the input of family and friends, professors and guidance counselors.

Many of the women interviewed were attracted to the profession after seeing what a profound impact it could have on lives.

I was purely an administrative assistant. Once, I was invited by my boss into a client meeting with a man who had laid tile his whole life. But he and his wife saved, and he lived well below his means and he was going to be okay financially. This man did not see himself that way. He really saw himself as much less successful. As my boss is presenting this plan saying, “Not only are you going to be fine, you can do whatever you want to, within reason. You can live the retirement you want to live, you can give to the kids. You can leave a legacy.” And this man starts crying. Which there’s no chance my boss could have predicted that. He couldn’t have orchestrated that if he had wanted to. It just happened to work out that I was in that meeting. I was sold on the career for life.

Most women in financial advice shared in interviews that they love to help their friends and other people, how they love personal finance, and find this industry to be a great fit. They see this industry as a “positive industry where you get to make a positive impact on other people’s lives.” These talking points about transforming lives and helping people are not clearly articulated to potential entrants to the profession.

Section 4

Advancement of Women in Financial Advice Careers

While getting women into financial advice roles is often the primary concern, the understanding of how to retain women in wealth management is just as important. The barriers listed previously – work/life balance, finding a mentor, finding a firm that’s a culture fit, discrimination – were not barriers to entering the profession. Rather they were barriers to success for those who have already started their career. Each of these barriers represents a factor that can increase retention risk. Beyond the barriers listed, a perception that women advance at a slower rate to their male counterparts also creates retention risk.

For women in wealth management, critical evidence of access to advancement comes in the form of existing women in leadership. Nearly three quarters of respondents (73.65%) said that women were part of their firm leadership, with very little difference reported by men and women.

While the survey responses indicate the presence of women in leadership, the comments indicate that there are few.

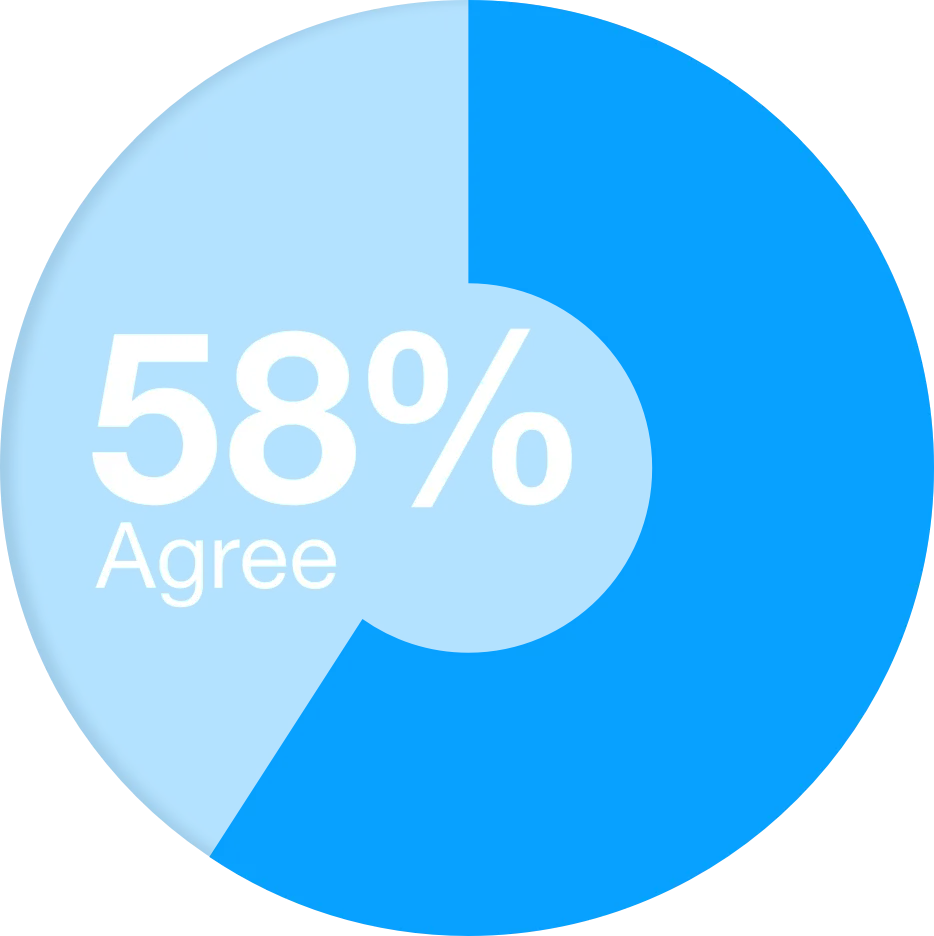

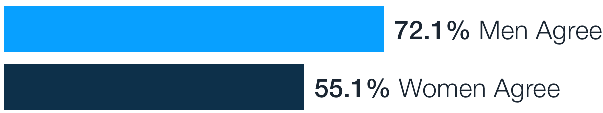

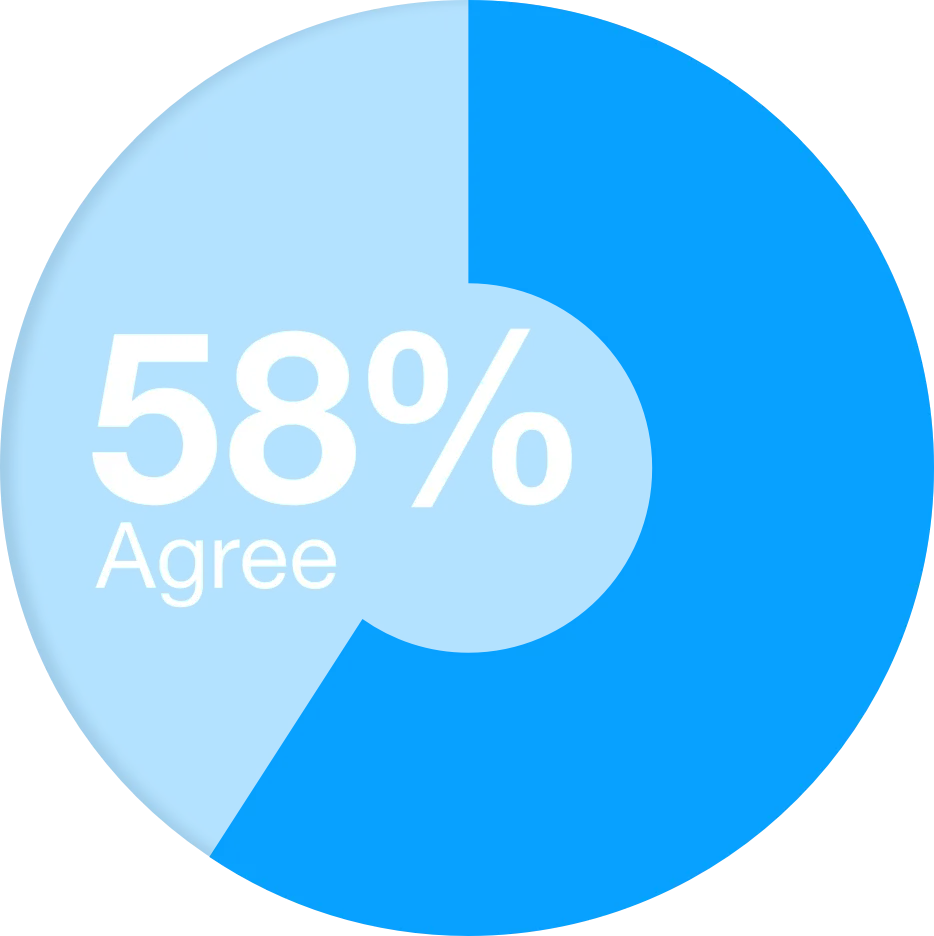

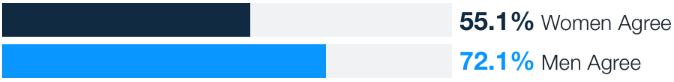

Intentional career pathing within firms can help ensure visible opportunity for all firm employees – men, women, advisor and operational. The firms of 58% of the respondents have implemented some sort of career pathing opportunities within their organizations. When that number is broken down by how each gender sees it, however, 55.1% of women believe this is true, compared to 72.1% of men. Career pathing and thinking through intentional advancement for all firm employees is a positive step forward.

73.7%

Agree that women were part of their firm leadership.

“[There are] so few women to look up to that we often need to pave the way.”– Survey Respondent

Firm has implemented some sort of career pathing opportunities within their organizations

Firm has implemented some sort of career pathing opportunities within their organizations

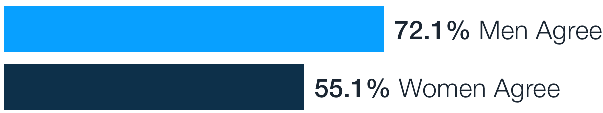

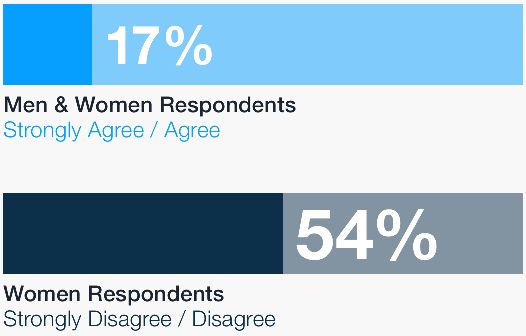

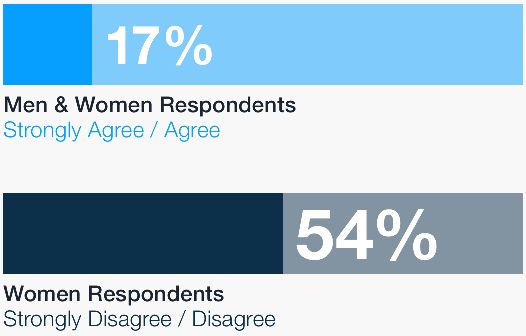

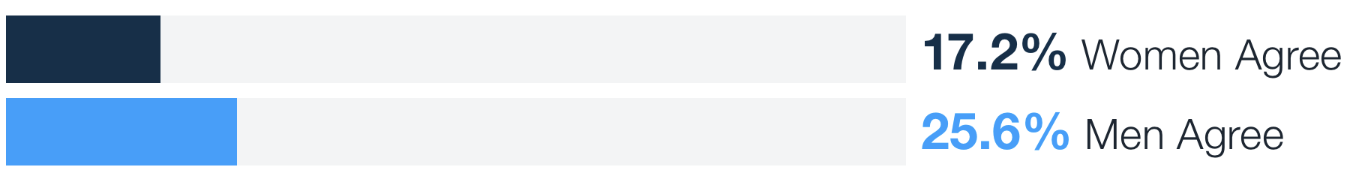

A more troubling finding concerns the perception among female advisors that their gender plays a role in receiving offers for joint work with other advisors, a factor in long-term advancement. In response to the statement “Financial advisors rarely take gender into account when seeking partners for joint work,” only 17% of all respondents strongly agreed or agreed and over half of female respondents (54%) either strongly disagreed or disagreed. Females were significantly more pessimistic than male advisors. This may also indicate a belief that male advisors don’t often see female advisors as a viable option upon transitioning their book of business.

A more troubling finding concerns the perception among female advisors that their gender plays a role in receiving offers for joint work with other advisors, a factor in long-term advancement. In response to the statement “Financial advisors rarely take gender into account when seeking partners for joint work,” only 17% of all respondents strongly agreed or agreed and over half of female respondents (54%) either strongly disagreed or disagreed. Females were significantly more pessimistic than male advisors. This may also indicate a belief that male advisors don’t often see female advisors as a viable option upon transitioning their book of business.

Financial advisors rarely take gender into account when seeking partners for joint work.

Financial advisors rarely take gender into account when seeking partners for joint work.

When Women Feel Welcomed, Accepted, and Appreciated

The first part of each interview included a discussion about what caused women to stay in the industry and helped them to thrive.

What is immediately obvious in the conversations is that it was often the small, but intentional, choices of the firm that meant the most. Most women shared stories about being included in meetings, being assigned major projects, and empowered to take on more responsibility. Often this direction comes from male superiors and colleagues.

Women were proud to be recommended for educational opportunities, recognized through industry awards, and being nominated to be part of industry study groups. Other factors were more subtle. Women feel accepted and appreciated when they are seen as a trusted resource within their office, when they feel as though their voices are heard and respected, and when others advocate on their behalf. Importantly, women feel accepted and appreciated when they are believed and supported when others behave inappropriately.

When Women Feel Unwelcomed, Unaccepted, and Unappreciated

While the survey did not specifically mention harassment, hostile work environment or assault, it came up often during the interviews as one of the primary reasons women choose to leave the profession before they’ve achieved the success they want. From demeaning language in the office to inappropriate physical advances, nearly every female interviewee had a story to share.

Multiple women shared being mistaken for the assistant, and often treated as one even when her role was clarified. One woman was told by a male superior that becoming an advisor was a “bad move” for a working mom, discouraging her from even joining the industry.

Other women said they received discouraging remarks about their physical appearance or clothing. One respondent was told she would never make it because she was not pretty enough. Another was called an inappropriate name when it was her turn to speak in her study group, prompting laughter from other men.

Another recurring response highlighted the importance of safety for women at events. The general rule shared repeatedly in the interviews is that if an event involves alcohol, women did not feel safe to stay past 9 p.m. Some women said they skip events after dinner as a general rule, seeing this as a loss of important networking time, but required for their safety.

I was at a meeting with all the management team and I said “Hey, guys. Great, great day. I’m going to go up to my room.” Someone I knew as an acquaintance followed me into the elevator…all of a sudden I feel my hair being stroked and pulled at. And when the elevator doors opened he grabbed my arm and tried to pull me out onto the floor. That was appalling. I had to work with this person every day and I never felt seen as an equal because he felt that he could do something like that.

The prevalence of such experiences underscores why many women simply don’t feel appreciated or accepted working in wealth management.

Section 5

Finding and Working with Clients

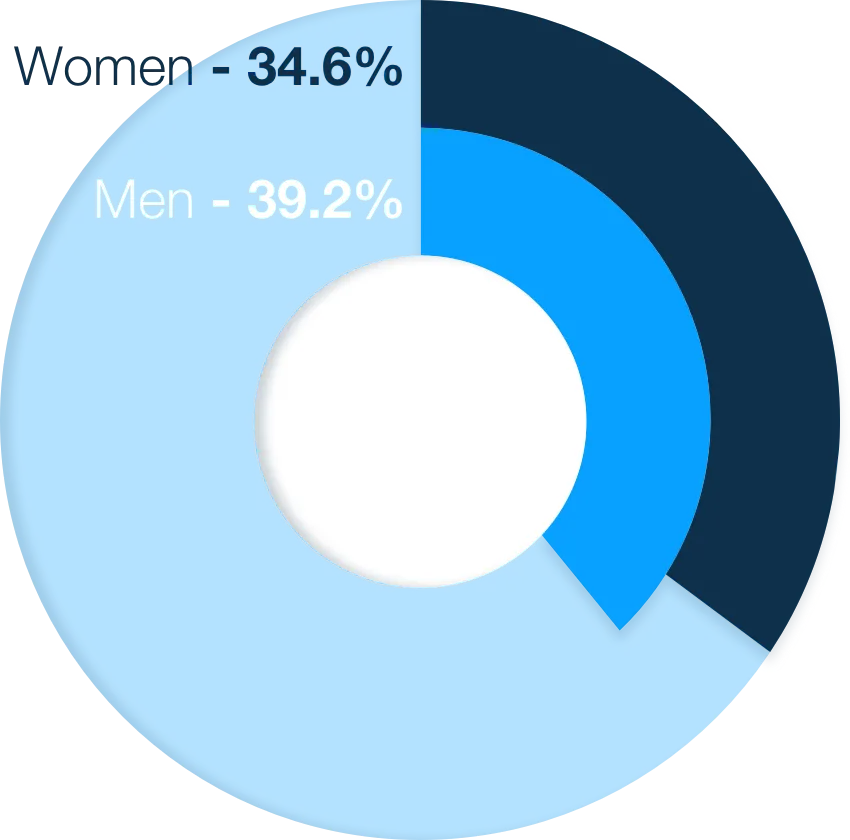

Within the industry, there’s a pervasive belief that prospecting clients is one of the core challenges women in wealth management face and a barrier that keeps them from entering the industry. However, only 34.6% of women surveyed cited prospecting as a barrier to success in the profession. Men were slightly more likely (39.2%) to label prospecting as a barrier to success.

Practice Makes Perfect

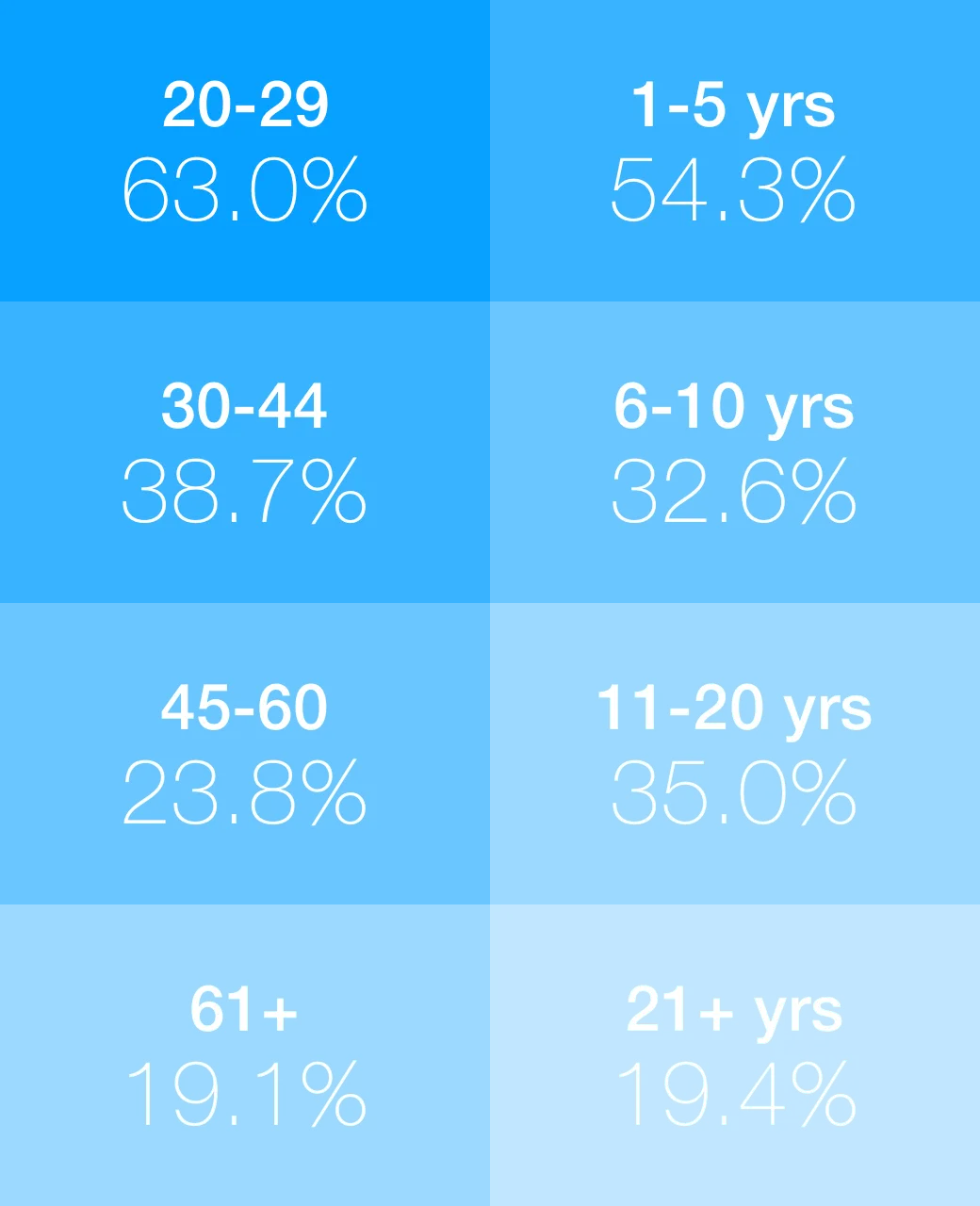

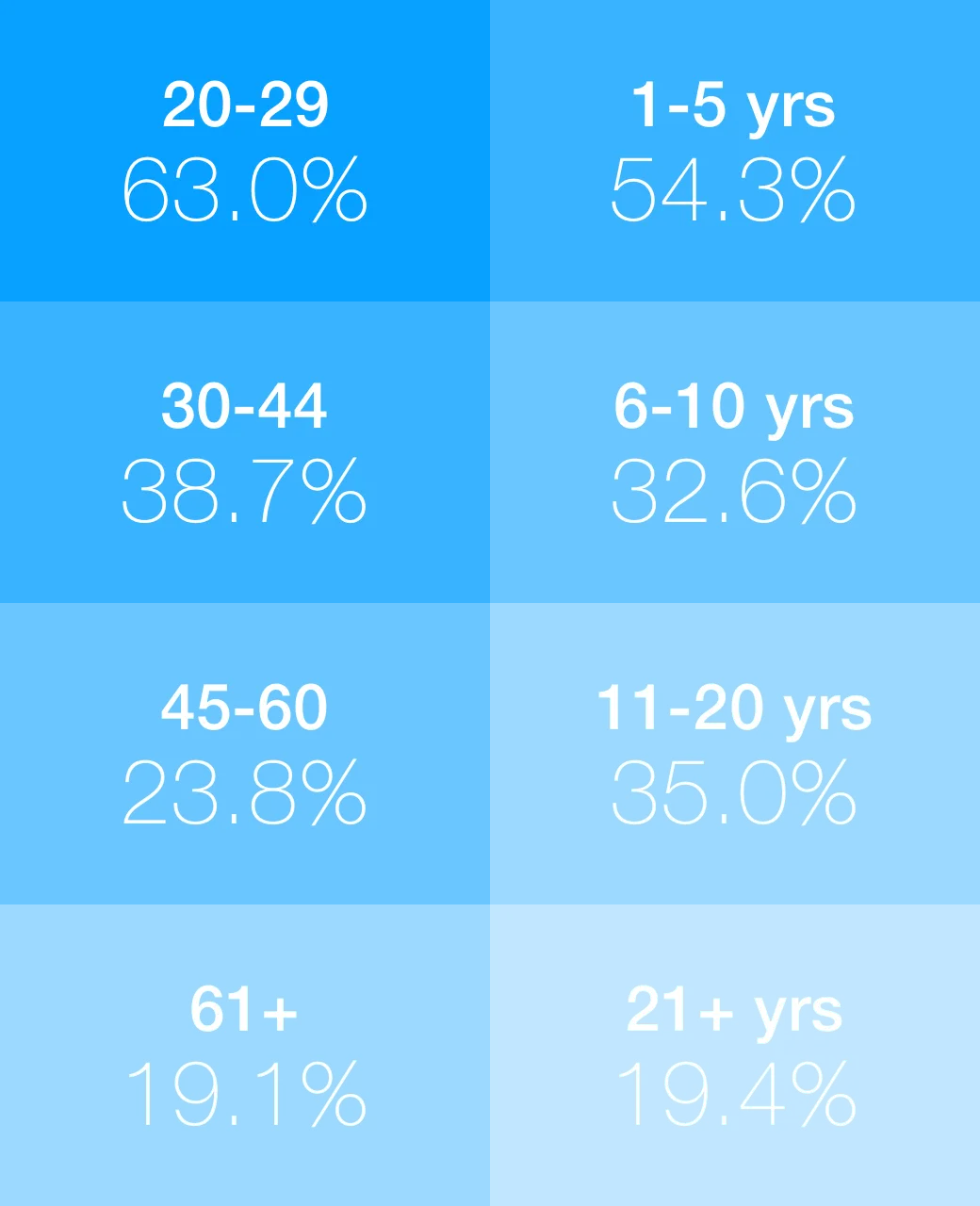

When this data is broken down by age and tenure within the industry, a more nuanced story emerges. While concerns about the ability to successfully engage in business development were high among young female advisors (with 63% of women in their 20s either agreeing or strongly agreeing that prospecting was a barrier to success), this number declined significantly for women aged 30-44 (39%) and continued to decrease as women aged (24% for women between 45-60 and 19% for women over 60).

This indicates what all seasoned advisors know: Developing your client acquisition pipeline gets easier over time, not only because the advisor becomes a more skilled prospector who better understands what types of clients will most benefit from her practice, but because the advisor’s social and professional network compounds over the years, creating a more opportunities for referrals.

It also indicates that the fear of prospecting may, in fact, serve as a barrier to entering the profession for female students. Naturally, everyone wants to pursue a career that aligns with their skills and aptitudes. If a student is uncertain in her ability to “sell” her services and expertise, as most college graduates (male and female) are, she’s less likely to pursue that career path.

This presents the industry with an opportunity to educate female students entering the profession that business development not only gets easier, but also may not actually be the obstacle that they think.

When this data is broken down by age and tenure within the industry, a more nuanced story emerges. While concerns about the ability to successfully engage in business development were high among young female advisors (with 63% of women in their 20s either agreeing or strongly agreeing that prospecting was a barrier to success), this number declined significantly for women aged 30-44 (39%) and continued to decrease as women aged (24% for women between 45-60 and 19% for women over 60).

This indicates what all seasoned advisors know: Developing your client acquisition pipeline gets easier over time, not only because the advisor becomes a more skilled prospector who better understands what types of clients will most benefit from her practice, but because the advisor’s social and professional network compounds over the years, creating a more opportunities for referrals.

Female advisors who see prospecting for new clients as a barrier to success

It also indicates that the fear of prospecting may, in fact, serve as a barrier to entering the profession for female students. Naturally, everyone wants to pursue a career that aligns with their skills and aptitudes. If a student is uncertain in her ability to “sell” her services and expertise, as most college graduates (male and female) are, she’s less likely to pursue that career path.

This presents the industry with an opportunity to educate female students entering the profession that business development not only gets easier, but also may not actually be the obstacle that they think.

Female advisors who see prospecting for new clients as a barrier to success

Cited prospecting as a barrier to success in the profession

Gender Stereotypes and Advisor Selection

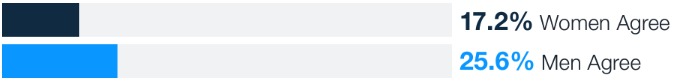

Perhaps less optimistically, women respondents report that gender still plays a role when prospects and clients select a financial advisor. In response to the statement “Prospects and clients rarely take gender into account when selecting a financial advisor,” 65.57% of respondents disagreed and only 13.77% agreed, indicating a pervasive belief rooted in advisor experience that many clients prefer a certain gender.

There was a significant variance between how male and female advisors perceived the role of gender when clients select an advisor. Only 13% of women expressed agreement that clients rarely take an advisor’s gender into account, compared to 21% of men. A full 70% of women and 49% of men disagreed with the statement.

Prospecting Opportunity Parity

While advisors are seeing stereotypes as a reality from the client side, they’re seeing it less within their firms. When asked if support for prospecting was equally available to both male and female advisors, 48.8% agreed that it was, with only 20.06% believing it was not. There was no significant difference in how male and female advisors viewed the prospecting support they received at their firms.

Female advisors also became more inclined to agree that they had equal access to prospecting opportunities with experience – but only to a point. Those with more than 20 years of experience are more likely to believe they’re at a disadvantage when it comes to prospecting support than those with 11-20 years of experience.

Prospects and clients rarely take gender into account when selecting a financial advisor

Prospects and clients rarely take gender into account when selecting a financial advisor

Prospecting Opportunity Parity

While advisors are seeing stereotypes as a reality from the client side, they’re seeing it less within their firms. When asked if support for prospecting was equally available to both male and female advisors, 48.8% agreed that it was, with only 20.06% believing it was not. There was no significant difference in how male and female advisors viewed the prospecting support they received at their firms.

Female advisors also became more inclined to agree that they had equal access to prospecting opportunities with experience – but only to a point. Those with more than 20 years of experience are more likely to believe they’re at a disadvantage when it comes to prospecting support than those with 11-20 years of experience.

“Female advisors feel like they need to know so much in order to competently serve their clients; male advisors seem to focus less on what they know and more about gathering assets, which is how advisors are compensated for the most part.”– Survey Respondent

Agreed that opportunities for support in prospecting for new clients are equally available to male and female advisors

Agreed that opportunities for support in prospecting for new clients are equally available to male and female advisors

An examination of this perception by age (rather than years of industry experience) shows a similar and more pronounced pattern. Female advisors indicate that as they age, they’re seeing unequal access to prospecting opportunities, with a shift in belief happening in middle age (between 45 and 60) and continuing to decline beyond 60.

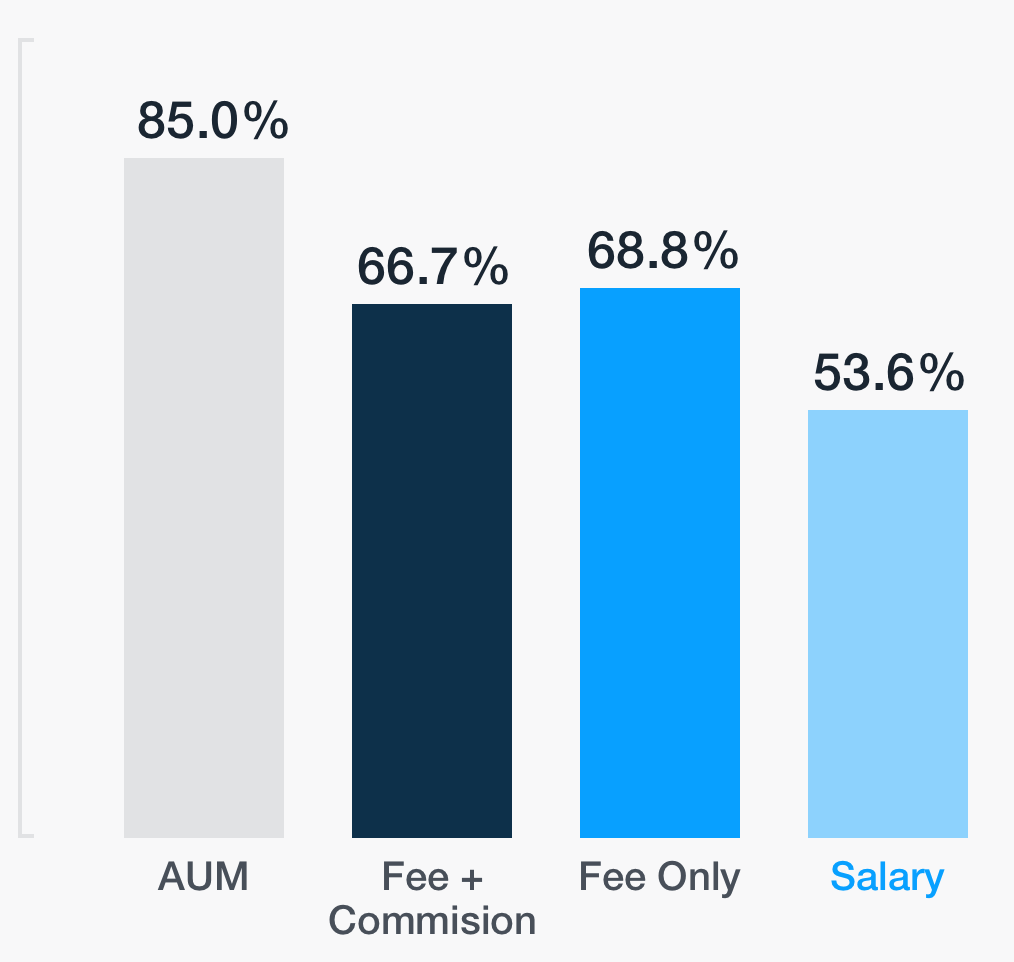

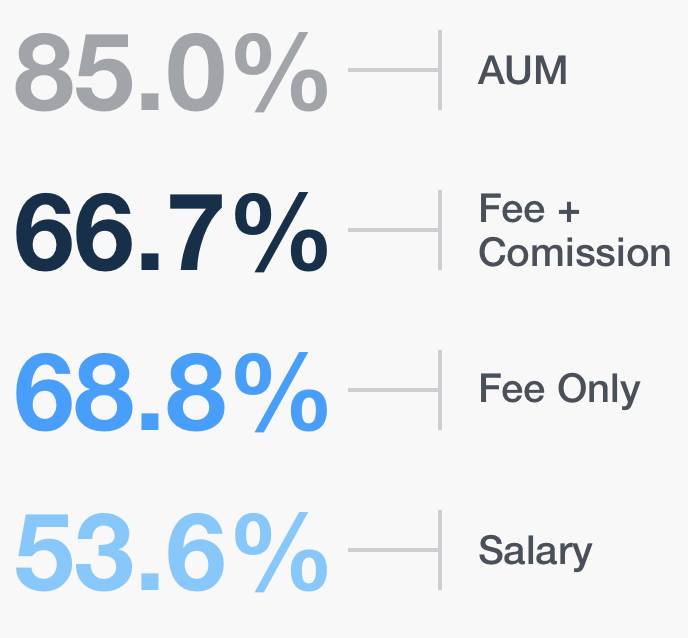

Interestingly, neither gender, age nor industry experience was the primary difference maker when it came to the belief of a female advisor that she had equal opportunities for prospecting. What compensation model the female respondent worked within was the single most predictive factor of her perception of equal opportunity.

Women working within a model where they earned based on assets under management were significantly more likely to agree that they had equal opportunity to prospecting than all other compensation models. Salaried advisors are the least likely to believe they’re getting a fair shake.

That said, the interviewees articulated a strong aversion to a commission-only compensation model and regarded it as a significant barrier to entry of the profession. Female owners shared their lack of desire to sell, instead choosing to grow their firms exclusively through referrals. According to these women, this referral model serves them well. The move toward fee-based services may be more attractive to women, according to interviews. It would appear the move towards this model is limited to a particular client base and far from being widely adopted. Until it is, firms would do well to find a way to capitalize on the relationship-building skills of their female advisors.

What compensation the female respondent worked within was the single most predictive factor of her perception of equal opportunity in prospecting.

What compensation the female respondent worked within was the single most predictive factor of her perception of equal opportunity in prospecting.

Section 6

Differing Opinions

Across respondents, female and male respondents generally agree about both the importance of the representation of women in wealth management. Disagreement cropped up in the opportunities for advancement available to female advisors. While some variance naturally existed in all questions, some areas have noteworthy divergence. As a reminder, survey respondents were 79% women and 21% male.

Where Men and Women Agree

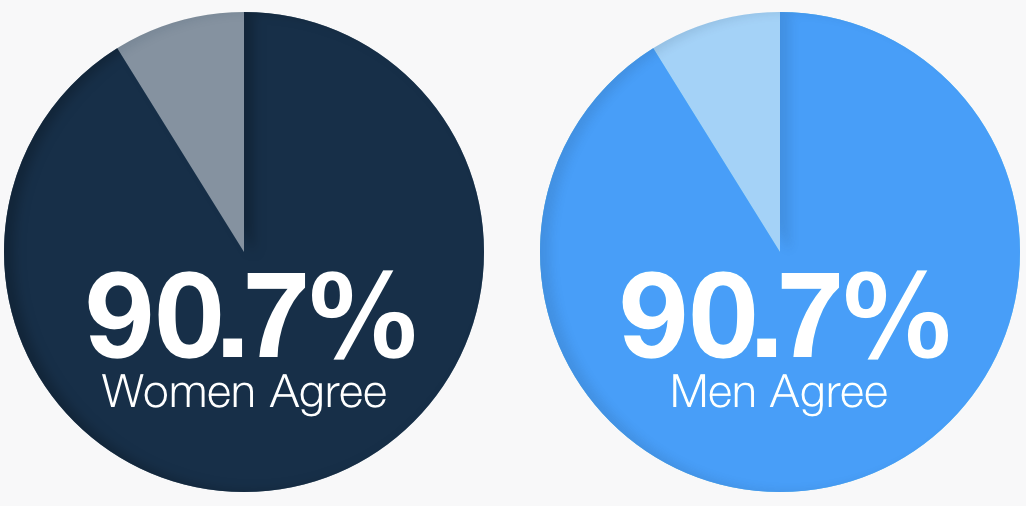

When it comes to recognition of underrepresentation of women in financial advice, men and women in the industry largely agree: It’s a problem – and a big one at that. This is significant because it indicates an openness to conversations about problem causes and solutions.

While both men and women agree that underrepresentation of women in financial services is a problem, the gap in their agreement on these action questions indicates that they don’t agree on why. The two areas where misalignment in perceptions appears are firm/industry behavior and the acknowledgment of bias.

Firm/industry behavior refers to the actions being taken by the respondent’s firm or the industry at large to address underrepresentation of women. More male respondents seemed to feel that their firms and the industry were taking the right steps and seeing results.

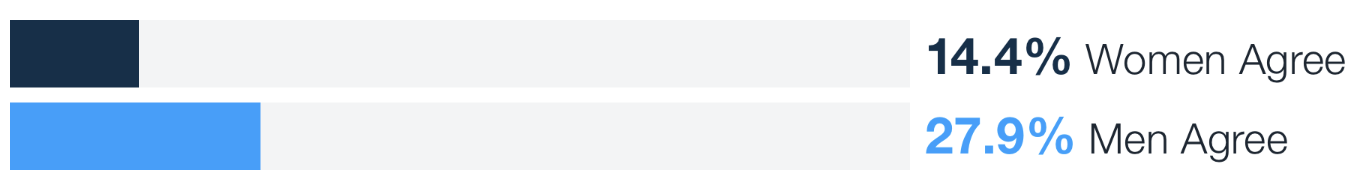

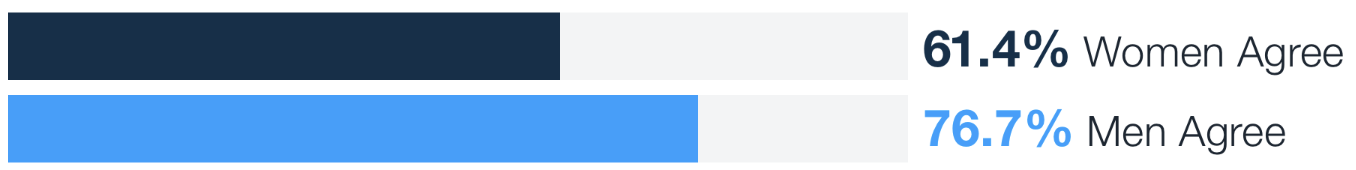

In response to the statement “the firm I work for has implemented career pathing opportunities for female advisors,” 72% of male respondents either strongly agreed or agreed as compared to 55% of female respondents, indicating that those who would most benefit from transparent career pathing are not seeing the availability of those opportunities. Similarly, more men feel that their firms are doing a good job promoting the profession to female students, 27.9% of men agreed that “Industry organizations and firms effectively promote a career as a financial advisor as attractive to female students,” compared to 14.4% of women, who were once the female students the industry was trying to recruit. And when it came to the firms where they worked, more male respondents felt that their firms were successful at creating equal opportunity for both male and female advisors (76.7% vs 61.4%).

One male advisor expressed his challenges to recruit female advisors even when actively pursuing them.

“Women want to work for women. What do you do when you have no women? We posted a job and no women applied. A female colleague did the same and received several applications from women.”

Acknowledgment of bias refers to the recognition of sexism or discrimination at play in the workplace, both in terms of how clients select advisors and how financial advisors choose other advisors for joint work – both being crucial for the long-term success of an advisor’s book of business. Men were less likely to see discrimination in both cases.

When it comes to recognition of underrepresentation of women in financial advice, men and women in the industry largely agree: It’s a problem – and a big one at that. This is significant because it indicates an openness to conversations about problem causes and solutions.

While both men and women agree that underrepresentation of women in financial services is a problem, the gap in their agreement on these action questions indicates that they don’t agree on why. The two areas where misalignment in perceptions appears are firm/industry behavior and the acknowledgment of bias.

Firm/industry behavior refers to the actions being taken by the respondent’s firm or the industry at large to address underrepresentation of women. More male respondents seemed to feel that their firms and the industry were taking the right steps and seeing results.

The underrepresentation of female financial advisors is a problem that should be taken seriously by industry organizations and firms.

The underrepresentation of women is one of the most urgent problems facing the financial advice profession.

In response to the statement “the firm I work for has implemented career pathing opportunities for female advisors,” 72% of male respondents either strongly agreed or agreed as compared to 55% of female respondents, indicating that those who would most benefit from transparent career pathing are not seeing the availability of those opportunities. Similarly, more men feel that their firms are doing a good job promoting the profession to female students, 27.9% of men agreed that “Industry organizations and firms effectively promote a career as a financial advisor as attractive to female students,” compared to 14.4% of women, who were once the female students the industry was trying to recruit. And when it came to the firms where they worked, more male respondents felt that their firms were successful at creating equal opportunity for both male and female advisors (76.7% vs 61.4%).

One male advisor expressed his challenges to recruit female advisors even when actively pursuing them.

“Women want to work for women. What do you do when you have no women? We posted a job and no women applied. A female colleague did the same and received several applications from women.”

Acknowledgment of bias refers to the recognition of sexism or discrimination at play in the workplace, both in terms of how clients select advisors and how financial advisors choose other advisors for joint work – both being crucial for the long-term success of an advisor’s book of business. Men were less likely to see discrimination in both cases.

Where the Perspectives Diverge

Industry organizations and firms effectively promote a career as a financial advisor as attractive to female students.

The firm I work for has implemented career pathing opportunities for female advisors.

Prospects and clients rarely take gender into account when selecting a financial advisor.

Financial advisors rarely take gender into account when seeking partners for joint work.

Male and female advisors have equal opportunity for success at my firm.

Where the Perspectives Diverge

What It All Means

Looking at where there’s significant variation in the perceptions of men and women is noteworthy. If there is a disagreement on the nature of the challenges, then there is less likely to be institutional or individual will to overcome these challenges. In other words, if male advisors (who make up the vast majority of the profession), believe that there’s no gender-based discrimination at all, there will be little urgency behind trying to make the changes that create more opportunity and access. In short, the data identify some specific areas of improvement on how well the majority of advisors understand the experiences of their female colleagues, and that these female colleagues will need to make the case that these changes are both needed and important.

Section 7

Current and Proposed Solutions

So what’s a firm (and an industry) to do when it comes to addressing underrepresentation? Based on the barriers that women in wealth management recognize and their thoughts about what would be most helpful, several options are available – and they all start with firm culture.

One survey respondent summed up the most likely actions when providing her thoughts on what firms need to focus on:

“Female Mentors. Set career tracks. Trainings. Remote-friendly with tech support. Flexibility for caregiving. Men stepping up and doing more caregiving work and that being the societal norm. Both men and women taking full parental leaves. Both men and women taking time off. Both men and women setting boundaries. Educate men on barriers for women so they can help. Pay more so we can hire out more help.”

And if firms aren’t willing to listen to the women on their teams, another respondent has a solution.

I am now a one-woman show. My experience has been that either women have to join other women-owned firms or launch their own firms.

– Interview participant

When asked what they wanted from their firms to better support their success, their fulfillment and their willingness to stay in the profession, the six most common themes supplied (in order of frequency) were as listed.

The first five of these was mentioned more frequently than more commonly implemented initiatives like focused recruiting and sexism training. The sixth was the primary solution derived from interviewees.

1Flexibility

2Training and education support

3Mentorship

4More women to leadership

5Clear career pathing

6Zero tolerance policies on discrimination, harassment and assault

Flexibility

Flexibility issues were named twice as often as the next most frequently named theme. Respondents want to come and go as they please, and work from the most convenient location. Women in particular, due to their disproportionate family responsibilities, prize workplace flexibility more than ever. Firms should allow all advisors to choose how to spend their time and emphasize outcomes over time at a desk. Allow teams to schedule their weeks with respect to their personal commitments. Provide tech-support (even if it’s an outsourced service) to those who work remotely or a hybrid schedule.

Women who are already experiencing this flexibility, and can set their own hours and craft their own schedules, cite that as one of the best things about the profession.

It is important to note that women are not asking for fewer hours. They clearly understand the need to work hard and work long, but they are looking for the opportunity to determine when they work those hours. The size of the firm can impact the availability of flexible work schedules. Small, independent offices are either fully on board or firmly against flexible schedules, depending on the leadership. Large offices seem to be slow to adapt, according to interviewees.

Training and Education Support

Firms often bristle at the mention of training and education because their first reaction is that they’ll need to do the teaching. What respondents really want is support (financial and time) for their certification courses, tuition reimbursement, and professional development at conferences to grow their social networks and expertise. The good news is that this training makes each advisor, and thereby the firm, stronger performers.

“The industry hasn’t changed much in 25 years. Lots of talk about inclusion but difficult for many to walk the walk.”– Survey Respondent

Mentorship

Difficulty finding a mentor was one of the often-cited barriers for female respondents. While it’s difficult for small firms to set up mentorship programs, firms can take advantage of other networks of women in wealth management (WIFS, Females & Finance) and pay for memberships. This allows advisors to grow their social networks, find role models and mentors, and get a better sense of the career possibilities available to them.

Women are looking for guidance in their careers and in their practices. In the interviews, most women talk about successes often brought about through male mentorship, including helping guide them through early career challenges, learning strategic networking, and introducing them to important connections. This highlights the importance of male participation in mentoring women for success. After all, they comprise the vast majority of firm leadership across the industry.

As the research indicated, newer and younger advisors (men and women) view prospecting as a significant barrier. Understanding that this perception declines with experience, focused mentoring around prospecting can help address this issue. More and more firms are developing a “team” approach to prospecting, with junior advisors as client relationship managers or servicing advisors.

In this structure, there may be less of an emphasis on business development – or the sales-focused approaches that many in the survey expressed an aversion to – in the early years of an advisor’s career. In addition, creating a narrative that views the advisor–client relationship as an alliance engaged in pursuing the goals and dreams of the client reframes business development as a process of consulting, offering solutions and gaining alignment rather than “overcoming objections” and “closing the deal.”

“[Women] prefer a happier workplace where there’s emphasis on mental health and balanced work life, harmony and charity.”— Interview participant

Adding Women to Leadership

The very underrepresentation of women in the industry means that the pool of proven female wealth management leaders is limited. To expand the pool, look past proven and focus on potential. Who has shown she’s ready to be prepped for leadership? What’s the career path to get her there, and how can your existing leaders help make it happen? Having women at the leadership table isn’t just about having a role model to show others the way. More than that, it’s about ensuring that women are in decision-making roles to help craft company policy and culture in line with the lived experience of other women in wealth management. As seen in the “Differing Opinions” section, men don’t always perceive or acknowledge experiences of women.

In terms of visibility, women often discuss the lack of role models in the industry. One woman shared her experience of a recent meeting:

It is interesting to watch the room when everyone that’s at the conference is in one room. And then they say, OK, we’re splitting up, advisors are going to stay in this room and operations are going to go in the other room. Pretty much all the women leave the room and [my manager said], “I didn’t realize how bad it was.” Where are the other females? Where aren’t they? They’re not in the room at all. It [made] me feel like I didn’t belong.

When it comes visibility, women want to see more women in all levels of leadership in the financial services industry. As one individual shared, “People learn from seeing, and there are not a lot of women to see in the industry.” The particular positions women hold matter. Seeing women as heads of marketing and HR are one thing, but seeing women at the helm of sales organizations are rare. As another woman shared, “Don’t talk to me about representation in customer service… don’t give me tokens.”

Clear Career Pathing

In the fervor to recruit female advisors, firms often overlook a high-potential candidate pool right under their noses. Operations professionals – client services, back-office support, human resources – know your culture. They know your clients! Does your firm have an operations-to-advisor career track? Do your non-advisor team members know that becoming an advisor is even an option? This type of career pathing can help ensure that new advisors are culture fits (they’re tried and true, after all), and can speed up the onboarding time that’s associated with an outside hire.

Career pathing is just as important for those already in an advisor role. When you come in as an associate advisor, what’s required to get your own book of business? What’s required to manage a team? What certification, knowledge and achievements does an advisor need to reach the next level? Even without drawing out an individual career path for each team member, being able to show a general journey with clear thresholds – both for advisors and non-advisors – provides clear expectations, sets everyone up for high performance, offers ongoing motivation and gives people-leaders clear discussion points in employee coaching and reviews.

Zero tolerance policies on discrimination, harassment and assault

Both in offices and industry conferences, guidelines for behavior should be clearly spelled out and swiftly enforced. When a boilerplate policy is put into effect for the sake of optics, then not enforced when policies are broken, it sets a precedent for the organization and sends the message that the safety of female colleagues does not matter. Setting a policy is not enough. Enforcement steps that are followed fairly and consistently applied are what matter most.

With instances of discrimination/sexism being the No. 1 write-in by respondents when asked about barriers (47% of mentions), and second place going to mention of the “Old Boys Club,” (16%), there’s no way to complete this study without mentioning the impact of gender-based discrimination is still at play in the financial advice industry. While some embrace bias education programs, the Harvard Business Review found in its 2021 article that most bias trainings are largely ineffective, stating:

87% of the respondents indicated that at their firms, [bias] training doesn’t go much past explaining the science behind bias and the costs of discrimination in organizations. In fact, only 10% of training programs gave attendees strategies for reducing bias.6

While awareness training likely provides valuable context, firms need clear behavior standards, and standardized and objective hiring and promotion criteria. Without them, it’s too easy to let inappropriate or unfair behavior slide or to make advancement decisions based on “gut feeling” or general affinity.

The Power of Leadership

While not one of the top six solutions named, many recipients throughout the survey emphasized the importance of candid, open relationships with supervisors where they believe their concerns will be heard and addressed. The survey found 63.4% of women felt comfortable sharing obstacles with their leadership, compared to 72.1% of men. Financial services isn’t the only industry that places people in management roles based on their success as an individual contributor, rather than their aptitude as a people leader. Ensuring that those in supervisory positions know how to build high-trust relationships, hold people accountable and set clear standards for behavior is required to retain both male and female advisors.

“My boss’s boss says her job is for us to love our jobs. The trickle-down effect isn’t just lip service, she and my boss deliver. And people pay compliments, give credit where credit is due, and tout each other’s partnerships and accomplishments. Best culture I’ve ever been part of, hands down.”– Survey Respondent

The Need for Action

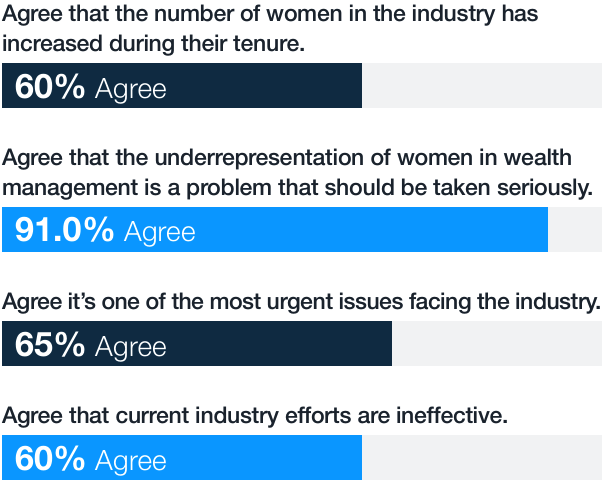

There’s no denying that there has been some movement in representation over the last three decades; 60% of respondents agreed that the number of women in the industry has increased during their tenure.

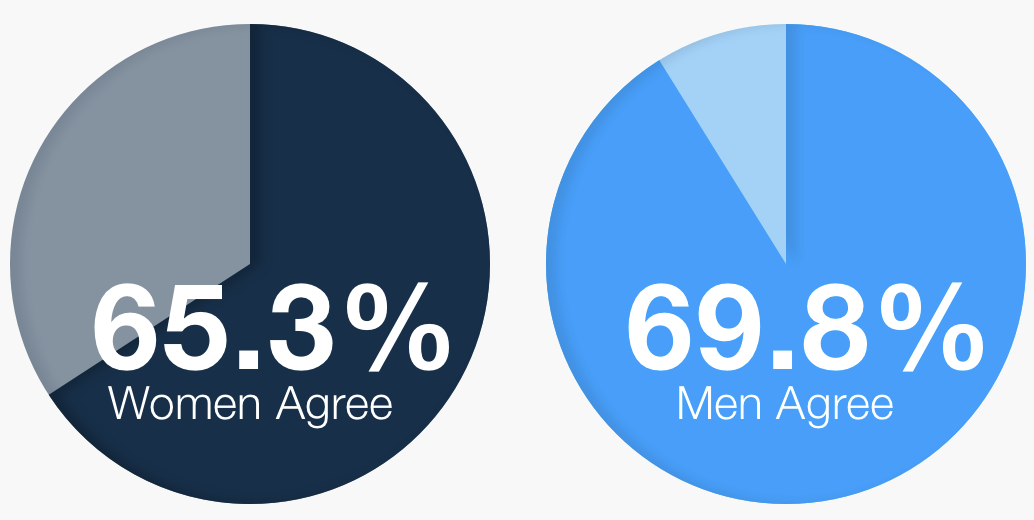

But with near universal agreement among respondents (91%) that the underrepresentation of women in wealth management is a problem that should be taken seriously, 65% agreeing that it’s one of the most urgent issues facing the industry, and 60% believing that current industry efforts are ineffective, the conclusion is that there’s still much to be done. Much of the work will fall on individual firms thoughtfully crafting policies addressing flexibility, education support, mentorship, intentional advancement of women, and, of course, sexism in the workplace.

This profession can be a wonderful one for women. Despite negative experiences in the industry, every female interviewee expressed a love of the work. Each felt they had found a way to make this industry the perfect fit for them. It will take significant effort and intentional actions on the part of women and men before we reach parity between the sexes in financial services. One interviewee put the imperative to do so succinctly:

“If we do the right thing and look at a broad range of potential candidates and see more diversity, it’s very good for our clients and we can make a huge difference in people’s financial health, dignity and well-being. So it’s not just a nice thing to do, it’s a smart thing to do.”

—Interview Participant

Stay Informed

Sign up to receive updates about the Women in Wealth Report, including a chance to participate in follow-up surveys.

1 CFP Board’s Reports & Statistics: CFP(R) Professional Demographics. https://www.cfp.net/knowledge/reports-and-statistics/professional-demographics

2 Women Make Great Financial Advisors. So Why Aren’t There More of Them?” Steve Garmhausen, Barron’s, June 7, 2019.

3 Diversity and Inclusion in Financial Advice 2020, American College of Financial Services, October 2022. https://womenscenter.theamericancollege.edu/sites/womenscenter/files/IN-Diversity-and-Inclusion.pdf

4 “Women Still Handle Main Household Tasks in U.S.” M. Brenan, Gallup, January 29, 2020 https://news.gallup.com/poll/283979/women-handle-main-household-tasks.aspx

5 “The Old Boys’ Club: Schmoozing and the Gender Wage Gap.” Zoe Cullen & Carlos Perez-Truglia, 2021. https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=57091

6 “Unconscious Bias Training That Works,” F. Gino and K. Cauffman. Harvard Business Review, September-October 2021