In my opinion, the trade war is over. There may be more tariffs to come, especially a few large tariffs on August 1st on a bunch of countries (50% for Brazil!), plus sectoral tariffs on things like copper, pharmaceuticals, semiconductor chips, and electronics. But even those may be postponed (in fact, pharma tariffs may actually be pushed out to 2027). Yet the latest trade deal with Japan is quite telling with respect to the direction of the administration’s trade policies, more so than the deals with the UK, Vietnam, and Indonesia. Japan’s an important trade partner for the US, and President Trump’s been upset with Japanese imports since the 1980s.

I’ll get to the details shortly, but the shape of the deal tells me that the administration wants to close deals sooner rather than later and be done with all the trade chaos. The best way to get there is to lower the tariff rate from Liberation Day rates (with a floor of about 15%), while securing commitments for investment in the US, and/or cutting some export deals. In fact, the US appears to be pursuing this same strategy with China – the tone has softened a lot, to the extent that the US is now allowing Nvidia to sell its less advanced H20 chips to China once again. It looks like the August 12th deadline is going to be postponed even further.

Even negotiations with the EU look to be heading to a place where the US imposes 15% tariffs on EU imports, a much better place than the threatened 30% tariff rate if there’s no deal by August 1st.

Between Japan, China, and the EU, along with Canada and Mexico, that pretty much covers 80-85% of US trade. In my opinion, that means we’re done with the trade war.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

Eighth Time Is the Charm with Japan

It’s taken a while for the US and Japan to reach a deal, with the Japanese side slow-walking things. Ultimately, it took eight rounds of talks to get a deal, with President Trump coming in to close. Things were barreling toward the August 1st deadline, and assuming no “TACOs”, Japan was facing a big increase in tariff rates. The US was probably feeling some pressure too (to avoid yet another deadline pushed further down).

The final details are yet to be hashed out, but here’s a broad outline.

What the US got was broader market access for American rice and cars. American cars will be built to US safety standards, rather than being subject to additional requirements. Japanese tariffs on US vehicles will be zero (though it was zero already).

Japan also apparently committed to $550 billion in investments in the US – there’s not much clarity around this, in terms of what exactly it’s going to be invested in and the timeline. We’ll have to wait for final terms. The White House says that the funds will be spent at Trump’s discretion, which makes things even more unclear since there’s going to be a question of how exactly it’s going to be structured (presumably, Japan would want a say too). On the other hand, the Japanese side says they’ll guarantee loans on investments up to $550 billion in areas relevant to their national security, including semiconductors, steel, shipbuilding, aviation, energy, and AI.

What the Japanese got was basically tariff relief, with a 15% tariff rate on exports to the US. This is especially huge for autos. Japanese vehicles currently face a 2.5% tariff when exporting passenger cars to the US, and a 25% tariff on light trucks (like SUVs) and commercial vans. But that was slated to go up by another 25% with the administration’s special sectoral tariffs on autos. Instead, Japanese vehicles will face a 15% import duty. A very good outcome for Japanese auto manufacturers given what they were facing. Meanwhile, US automakers still face a slew of tariffs on various inputs, including steel, aluminum, copper, and non-compliant USMCA goods (which amount to over 50% of imported goods from Canada and Mexico).

The Japanese ultimately ended up with more tariffs than before all this started, but a 15% tariff rate is far from the worst case. Especially relative to Liberation Day reciprocal tariffs. And all things considered, their automakers have come out in good shape – there’s a reason why Toyota’s stock surged 16% and Honda almost +12% on news of the deal.

The Nikkei 225 soared 5.5% after the deal was announced, powered by the automakers, and underlining what a relief this deal was for investors in Japanese stocks. In fact, the Nikkei is once again knocking on the door of all-time highs, hopefully putting its 36-year recovery (since the 1989 highs) firmly in the rear-view mirror.

What Did the US Get Out of the Trade War?

This is the big question. The war may be over but there’re consequences, and a bit of a hangover. After all, we do have more tariffs than at the start of the year, including 50% tariffs on steel, aluminum, copper (upcoming).

I thought it’d be useful to recap some of the original rationale(s) for imposing tariffs and use these to assess what the US got out of all this.

- Reshore manufacturing and shrink the trade deficit. To be clear, this would work via tariffs raising prices on imported goods, and so Americans would “buy American”. These goods would be more expensive than before but not as much as imported goods with a big tariff cost attached to it.

- Raise revenue. The cost of imports rise thanks to huge tariffs, filling government coffers. But this assumes that Americans continue buying imports without substitution.

- Level the playing field. Have other countries reduce trade barriers, boosting US exports and shrinking the trade deficit (even as US imports continue as before).

One concrete thing the US is getting is tariff revenue, to the tune of $100-$200 billion per year additional revenue from new import duties. That is not nothing, as it adds up to about $1 – $2 trillion in additional revenue over 10 years. It offsets some of the cost of the $3.4 trillion tax bill that Trump signed into law on July 4th (the cost will balloon to $4.7 trillion if temporary provisions are made permanent). The original claim was that tariffs would bring in about $700 billion of revenue per year, more than offsetting the cost of the tax cuts over the next decade.

At the same time, more tariff revenue means higher prices for goods. After all, someone is paying the tariffs, and it looks like the brunt of it is falling on consumers, rather than foreign exporters or even US businesses. However, the price increases are likely to be a one-time event, which is not a bad thing – though it could show up in inflation data over several months because of how things are measured and how and when companies choose to push costs to consumers. Also, the price increases are not expected to be significant given the level of tariffs we appear to be settling at, or at least nothing like what we saw in 2022 amid the supply-chain crisis. But it also means there’s not much incentive for Americans to substitute purchases away from imported goods to American goods. So, imports are unlikely to fall significantly (unless we go into a recession and demand falls, reducing imports). In short, not much reshoring because of tariffs.

All in all, the tariff rate is not high enough to make a big impact one way or the other, whether to offset the cost of tax cuts or incentivize reshoring of manufacturing, but it’s high enough that consumers will feel it in prices. At least temporarily.

There have been announcements of new investments intended to be made by foreigners here in the US, including Japan but also from the Middle East. The timeline is very unclear, and the devil will be in the details. But here’s the thing, if more capital is flowing into the US, that means the current account deficit (which is mostly the trade deficit) is increasing – no two ways around it, as it’s a national accounting identity. The current account deficit is the opposite of the capital account surplus. If there’s more fixed direct investment (FDI) flowing into the US, that means the trade deficit is likely getting larger. Not smaller.

With respect to leveling the playing field, tariffs and non-tariff barriers were never really a problem for US exporters. In fact, US companies that want to sell products abroad make those products abroad (like iPhones, drugs, and even cars). Crucially, the profits actually accrue to the benefit of shareholders in the US (though not taxes on these profits, thanks to profit-shifting).

As an example, American auto makers are not going to make a car in the US and export it to Japan, especially with metal tariffs of 50%. Non-tariff barriers like safety standards are not especially cumbersome to get around if an automaker wanted to – European automakers do it all the time when exporting their vehicles to Japan. Most Japanese prefer smaller and more fuel-efficient vehicles (gas prices are much higher in Japan), rather than light vehicle trucks (SUVs, minivans) that US automakers mostly manufacture here in the US. Also, US-made vehicles are left hand drive, whereas Japanese cars have their steering on the right. Not to mention the fact that these large vehicles would hardly fit on Japanese streets – it’s not very appealing to do 7 point turns to make a u-turn, let alone finding parking.

As for emerging economies, they’re simply not wealthy enough to afford goods made in the US. The Vietnamese and Indonesians aren’t going to turn around and buy US-made goods, or if they do buy American goods, it’s going to be those that are manufactured abroad (and as I noted above, profits on these accrue to US shareholders).

The Real Hangover: Higher For Longer Rates

In my view, the main impact from the trade chaos of the last few months is that we have higher rates for longer. Powell himself admitted that they would already be cutting rates if not for tariffs. And given we’re starting to see some tariff impact in official inflation data, we may not see another rate cut until November or December.

There’s no question that policy is too tight, i.e. rates are too high. We’re seeing the adverse impact across the board, with the economy expected to grow just 1-2% in 2025, a far cry from the 2.5-3% expected at the start of the year:

- The labor market is still cooling, with aggregate income growth clocking in around 3% annualized in Q2 as payroll growth and wage growth eases

- Prices for services like airfares and hotels are falling, indicating lower demand amid softer wage growth

- Households are just about able to keep up with price increases and maintain current levels of spending, but consumption is not growing at the pace it was in 2023-2024

- Housing is struggling amid the weight of high mortgage rates, with low activity and sales

- Manufacturing is also struggling amid tariff uncertainty, along with higher costs for raw materials

This doesn’t mean the economy is entering a recession, but there’s clearly a slowdown in place. Cyclical areas like housing and manufacturing are weak amid the weight of high interest rates and tariff hangover. On the other hand, one thing going for the economy right now is the AI build-out, which we’re seeing in high-tech and equipment manufacturing. That’s going to be a positive contributor to GDP. Let alone profits for the big tech companies involved in these build-outs.

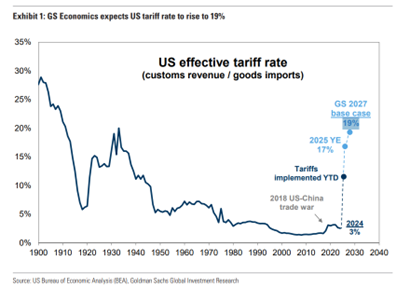

Coming back to tariffs, the average effective tariff rate is currently around 13%, about 10%-points higher than it was at the start of the year – which was pretty much the “best case” scenario for most analysts before Liberation Day. Goldman estimates that the average US effective tariff rate will rise to 19%, but that’s not expected until 2027. There’s a long way to go.

Given that the trade war is essentially over, and average tariff rates appear to be settling near the best-case scenario, it shouldn’t be a surprise that markets are hitting new highs, especially given the dominant AI theme right now. Earnings expectations are also rising as companies navigate around tariffs.

Real GDP running around 1-2% is not great, especially relative to the 2023-2024 pace of 3%, but the stock market surged in the 2010s amid below-trend economic growth. Of course, it was dominated by US large caps. And that may be the case once again over the next few years. One difference now may be that fiscal stimulus outside the US could boost international stocks, with a potential tailwind of a weaker dollar. As we discussed in our Midyear Market Outlook ’25, this is a big reason why we’re neutral weight international stocks in our tactical and strategic portfolios. Ryan and I chatted about a lot of these concepts in our latest Facts vs Feelings episode as well. Take a listen below.

For more content by Sonu Varghese, VP, Global Macro Strategist click here

8210631.1.-07.24.25A