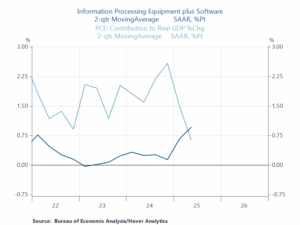

This chart from our friend, Neil Dutta, Head of Economics at Renaissance Macro, tells an absolutely incredible story if you ask me: it tells you that spending on artificial intelligence (both IT hardware equipment and software) contributed an average of 1.0%-point to GDP growth over the last two quarters. That’s more than the contribution of 0.7%-points from consumption. For perspective, consumption makes up 68% of the economy whereas IT equipment and software makes up just over 4%.

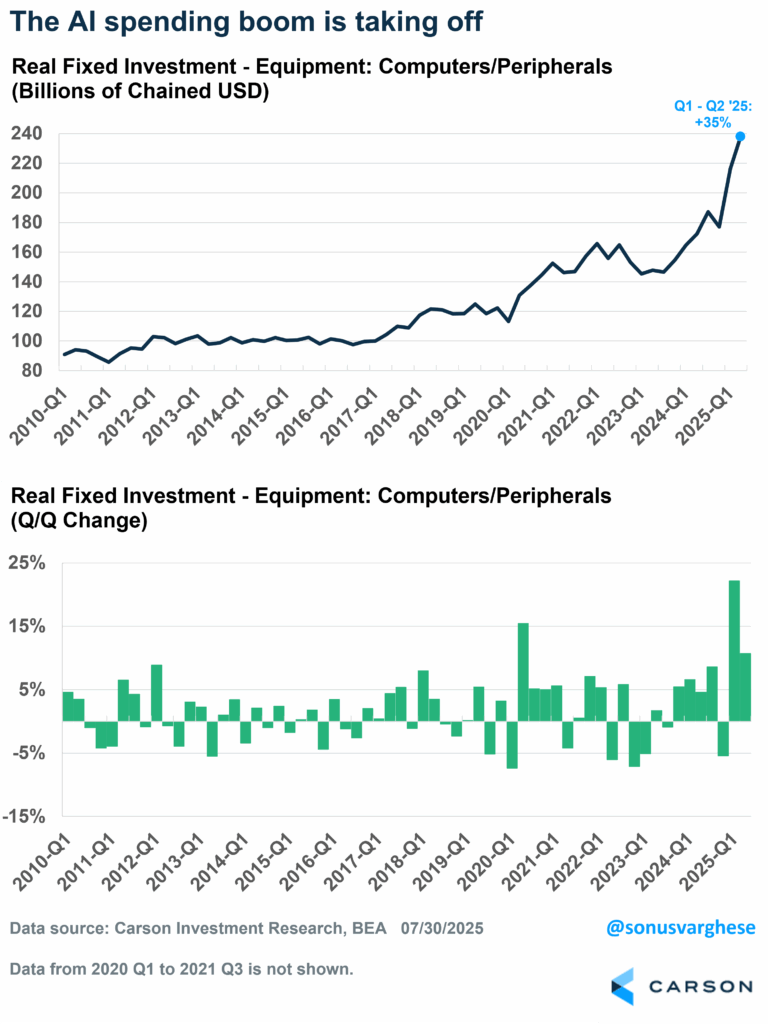

Digging into the data, here are some more numbers, and it’s quite incredible. Here’s how equipment spending on computers and peripheral equipment has increased recently:

- Nominal: +37% over the last 2 quarters and +65% over the last 2 years (29% annualized)

- Real (inflation-adjusted): +35% over the last 2 quarters and +62% over the last 2 years (27% annualized)

The fact that nominal and real numbers are close to each other tells you that this isn’t about higher prices. It’s literally “real.”

Software spending is also surging, though the numbers aren’t quite as eye-popping:

- Nominal: +3% over the last 2 quarters and +15% over the last 2 years (7% annualized)

- Real (inflation-adjusted): +9% over the last 2 quarters and +18% over the last 2 years (9% annualized)

What’s interesting in the above numbers is that real spending has actually increased faster than nominal spending. In other words, prices for software have fallen and actual usage has picked up.

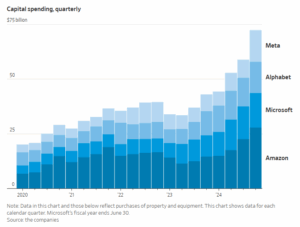

And this doesn’t look like it’s about to end anytime soon. The AI arms race is accelerating with the biggest tech companies only increasing their spending. In their recent earnings call, Meta said they anticipate full year 2025 capital expenditures (capex) to be in the range of $64-$72 billion and to grow by another $30 billion in 2026. Google said it plans to spend $85 billion in 2025 on capex related to the cloud and AI. Microsoft is going to outspend everyone—they’re planning to spend a record $30 billion on capex just in the current quarter, on the back of higher returns from its already massive investment in AI. Together with Amazon, these four companies alone are expected to spend close to $400 billion in 2025 on AI-related capex, about $120 billion more than in 2024 and more than what the EU spent on defense last year.

Morgan Stanley estimates $2.9 trillion in spending from 2025 to 2028 on chips, servers, and data center infrastructure (for perspective, that’s 10% of US GDP). In fact, the One Big Beautiful Bill (OBBB) is expected to spur further investment spending, as it provides tax relief for companies that frontload investments, freeing up cashflow. This underlines the opportunities from the tax bill that we discussed in our 2025 outlook, and more recently in our 2025 Midyear Outlook. It’s useful to keep in mind that one person’s (or business’s) spending is another person’s income. An aggregate boost in spending boosts aggregate income, which in turn increases consumer spending.

What’s the Other Side?

The common view is that AI will lead to job losses—in fact, we’ve seen significant layoff announcements at tech companies. At an aggregate level, the unemployment rate for recent college graduates is higher than the overall unemployment rate, and the popular narrative is that it’s because of AI. However, as a recent report from Employ America points out, this trend has been in place since 2018, whereas ChatGPT was released at the end of 2022.

If AI was driving unemployment higher for recent college graduates, then we would expect to see college majors with the highest exposure to AI experiencing greater increases in unemployment. But that’s not the case, and majors with AI exposure have experienced a range of outcomes, with some areas like Math, accounting, and business analytics seeing lower unemployment rates than pre-pandemic. The chart below shows the change in unemployment by major between 2017-2018 and 2023, with high AI-exposure majors in bold.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

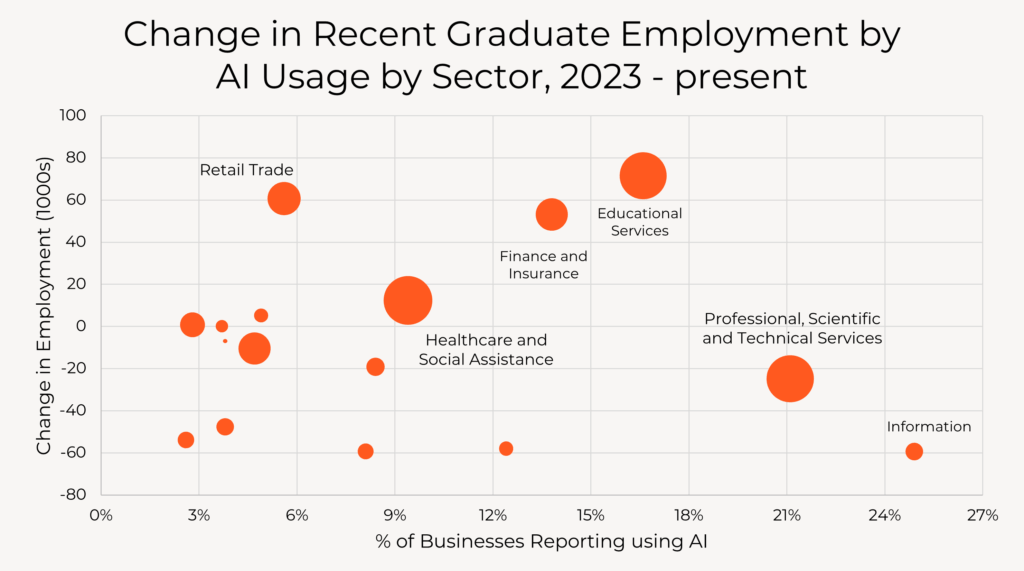

At a broader sector level, the data is mixed when it comes to employment for recent graduates, and points against the “AI is taking away jobs” hypothesis. While recent graduate employment (2023–present) has fallen in sectors like professional, scientific, and technical services and information services (which have had higher uptake of AI), recent graduates have seen higher employment in areas like educational services, finance, and insurance (which have also reported higher AI uptake). Even sectors with low AI uptake have seen notable employment reductions amongst recent graduates. I recommend reading the whole piece, which is fascinating (link).

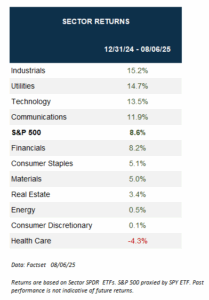

Rather than impacting employment, a more immediate consequence of the AI boom is that there is also an increasing need to power AI infrastructure, which is why Utilities are the second-best performing sector year to date, with a near 15% return. That is even better than the Technology sector (+13.5%), let alone the broad S&P 500 index (+8.6%).

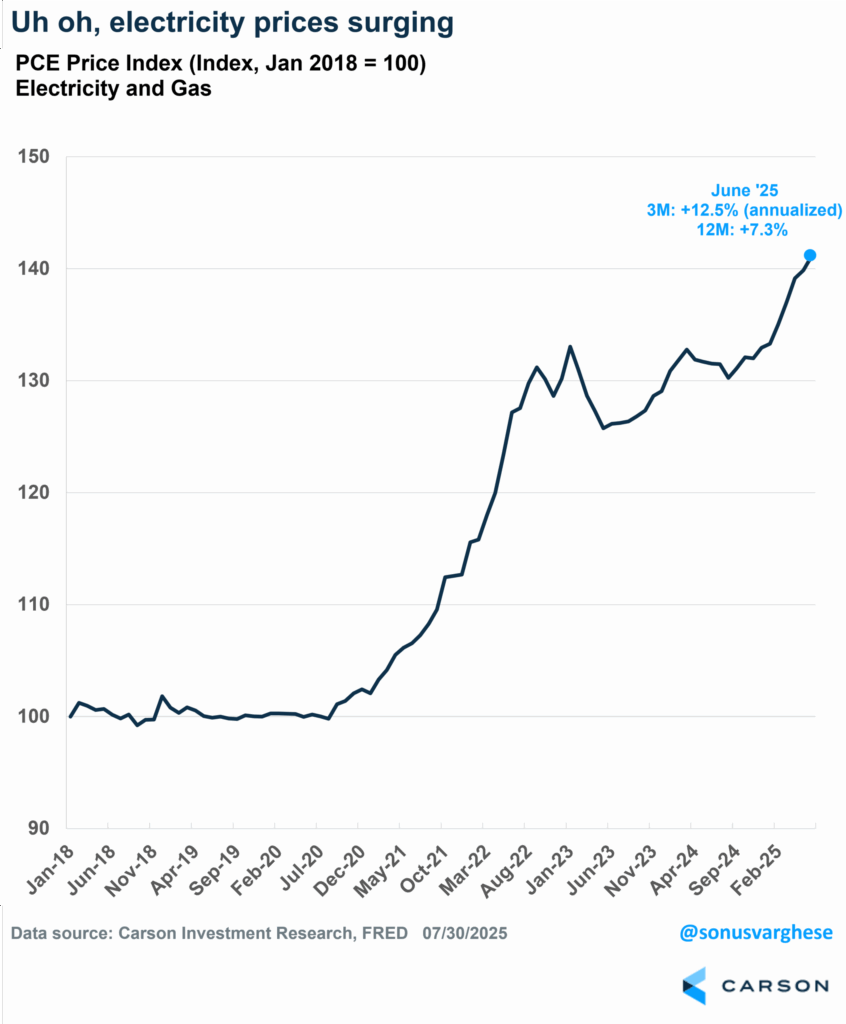

Electricity demand is surging, but supply is not keeping up. As a result, electricity prices are rising quite rapidly. Household electricity and gas prices rose at an annualized pace of 11% in June, and 12.5% over the last three months. The recent surge looks exactly like the surge in the AI equipment spending chart.

Accelerating electricity prices are offsetting the drop in gasoline prices, and will crimp household wallets, and spending in other areas—not everyone needs to fill up a car, but everyone needs to keep the lights on.

The other risk is that AI build-out hides underlying weakness in the economy, with markets also powering higher on the back of this theme. Cash-rich tech companies are going on a capex spending spree, providing a crucial boost to the economy, and as I discussed at the top, that doesn’t look like it’s ending soon. When combined with tariff-related inflation in core goods, that could push the Fed away from providing sufficient interest rate relief, which means rate-sensitive parts of the economy will continue to struggle.

The biggest longer-term risk is that a surge in investment spending, especially one that makes an outsized contribution to GDP for a few years, tends to lead to a fairly large hangover once it ends. We’ve seen this a few times over the last 30 years—the internet boom in the 1990s, housing and financial innovation in the 2000s, and energy (including shale) in the early 2010s.

From 1993 through 2000 (8 years), spending on computers and peripherals and software surged by 169%, an annualized pace of 13% per year. It subsequently pulled back by 8% over the next three years (2001-2003), an annualized pace of -2.7%. That doesn’t sound like a lot but a swing from +13% per year to -2.7% is significant. Over the 2001-2019 period, investment in this area grew at an annualized pace of just 4.2%. The chart below shows year-over-year growth rate from 1993-2019, and you can see the step down in pace after the dot-com crash in 2000.

At some point, I believe the return on investment for this spending will start to drop, and investment spending will collapse. This could result in a big swing in its contribution to economic growth, from the positive side to the negative side. That is not to say society doesn’t benefit from all the investment that happened during the boom time (although perhaps it’s a little harder to say that about the housing bubble and all the financial innovations we saw in the mid-2000s).

The problem is that it’s hard to pinpoint exactly when all this will happen, and that’s a big reason we remain overweight equities right now—essentially, riding the wave—but also are as diversified as we can be.

For more content by Sonu Varghese, VP, Global Macro Strategist click here

8262036.1-08.07.2025A