“If pro is the opposite of con, does that make progress the opposite of Congress?” -famous quip

On July 20, we passed the first six months of the second Trump administration, or 1/8 of the way into Donald Trump’s second term. Over time we have been updating our view of potential policy risks, within the context of initially seeing more market-friendly policy opportunities than risks. Despite seeing a rise in policy risks, opportunities have not disappeared. As a result, we have remained generally bullish on equity markets, maintaining our S&P 500 return target of 12–15% in our Midyear Outlook, which would be an above-average year.

We did our first policy risk update on March 26, with “Liberation Day” still ahead. Our conclusion at the time:

The opportunity for the potential tailwind has not been entirely lost, depending what happens with the tax bill, but it hangs by a thread and disruptions have been larger than expected. We have informally downgraded our GDP expectations with the potential upside we saw likely off the table. We are probably looking right now at something more like 2% GDP with risks more to the downside (but not recessionary) for 2025 versus something more like 2.5% with risks to the upside when we made our initial assessment. But we will continue to monitor both risks and opportunities for how they are playing out.

Since March, the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act (“OBBBA”) bill was passed on an aggressive timeline, we have had some clarity on tariffs (although things got worse before they got better), and we have seen measures of confidence improve or at least stabilize. Policy risks still tilt negative in our view, but they are still complemented by policy opportunities and the risks and opportunities have come into better balance.

Of the seven risks we discussed in March, we think risks around two of them have become worse (but one of them, tariffs, has seen substantial improvement since Liberation Day), two are unchanged, and three have improved. Importantly, the risk of a delay in passing the tax bill is completely off the table and the frontloaded deficit-financed spending in the bill will provide an additional cushion against economic disruption.

What we have started to see, however, is the bite of some policy missteps start to appear in hard economic data. GDP growth ran at an annualized pace of 1.2% in the first half of the year after running at close to 3% in 2023–2024 and trade disruptions were clearly a primary driver of the slowdown. We don’t think that’s a one off and believe we are likely to continue to see 1–2% annualized growth in the second half of the year.

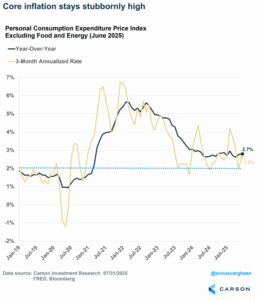

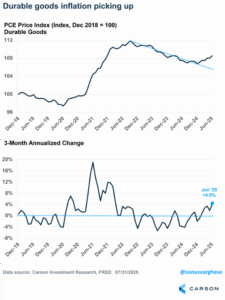

Also, while overall core Personal Consumption Index (“PCE”) inflation (the Fed’s preferred measure) remains steady, it’s still at a level still too high for comfort. We are also clearly starting to see some of the effects of tariffs underneath the hood. What many are missing is that there are also some disinflationary effects in play too, especially around shelter inflation, that have helped offset some tariff effects and will likely continue to help. But tariff effects are just starting to come into play and one important temporary factor that has held back inflation (financial services inflation, which reflects stock prices at a lag) will likely start to unwind. It’s also worth highlighting again that direct tariff effects cause a one-time change to price levels, even if that takes some time to flow through, but do not raise the long-term inflation rate, although added trade friction and any structural shift in inflation expectations can.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

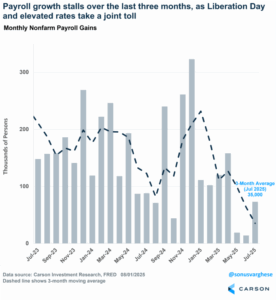

And, of course, there is the recent jobs report, including the revisions to prior months. Large downward revisions aren’t unusual during periods when there are major changes in the structure of the economy (as we’re seeing now) or during slowdowns. And while we always take data with the grain of salt it deserves, we would take the downward revisions as more signal than noise or modeling error. If anything, the revisions bring the jobs data more in line with relative weakness we’ve seen in other hard

One very important thing to remember when evaluating policy is that policy is not the fundamental driver of the economy or markets. There are larger macroeconomic forces in play that reflect the everyday decisions of households and businesses. Policy matters, especially at the margins, but the main economic forces are outside of policy. We often look for easy, clear causes for the things we see happening in the economy and pinning it on policy provides an easy explanation, especially if you’re politically engaged. In particular, we like to give the blame (or credit) to our presidents. But presidents (and Congress) are often given much more weight than they actually deserve in evaluating markets.

With that in mind, let’s take a closer look at our updated view of policy risks.

Risk 1: Tariffs Push Inflation Higher

Change Since March 6: Higher, but lower since Liberation Day

Risk Assessment: High

Immediate Market Impact or Slow Burn?: Both

When it comes to tariffs, the biggest risk we focus on is inflation, because that flows through to Fed policy and rate levels. We place less emphasis on tariff’s direct effect on the economy, although that’s not trivial. Right now, we would roughly estimate tariffs will cost about a percentage point of GDP in 2025, some of which we would probably get back in 2026. That’s the cost of the structural changes the president wants to make to our trade relationships. But because the tariff policy is an outlier compared to US trade policy of the last century, there’s a fair amount of uncertainty around those estimates.

We would actually say the overall risk from tariffs has moderated since Liberation Day simply because we have greater clarity and once companies have clarity they can work with it. (See Carson VP Global Macro Strategist Sonu Varghese’s “The Trade War Is Over. Thank You for Your Attention to This Matter.” for a deeper dive.) That’s directional improvement, and companies will probably be able to game the environment to a degree so that actual tariffs paid ends up being somewhat lower than expected. (Businesses are much better at finding loopholes than governments are at closing them.)

But let’s not overstate this. There’s no getting around the fact that tariff rates are high, currently estimated at 17-18%, which would still be the highest level since 1935. And selected comments from the most recent ISM Manufacturing Report highlights that many businesses still find the impact of tariff uncertainty a challenge.

Institute for Supply Management – 8.6.25

Because of some added clarity from a policy perspective, markets have been able to price in some of the tariff risk. A tariff level that sent markets into a tailspin when it was a surprise has been priced in more smoothly as we were able to get a clearer picture of the endpoint. There is still a possibility that some risks have not been priced in, but markets at this point are willing to wait and see.

Risk 2: The Federal Reserve Keeps Policy Too Tight

Change since March 6: Unchanged

Risk Assessment: High

Immediate Market Impact or Slow Burn?: Immediate Market Impact

This one is intimately tied to tariff uncertainty, which has handcuffed the Federal Reserve and remains a major risk. (Sonu discussed this in “The Economy Is Currently Being Held Up by AI”). The current market-implied expectation for additional Fed cuts this year is just shy of 2.5 cuts. We remain in the camp (which we’ve been in for a while) that policy remains too tight, especially given slowing aggregate wage growth. The economy has been incredibly resilient despite high rates, but cyclical sectors, including housing, small businesses, and manufacturing, have been under pressure. We think a slower path of rate cuts is very unlikely to push the economy into a recession on its own, but it will make the economy more sensitive to other shocks.

Risk 3: Unpredictability Restrains Animal Spirits

Change since March 6: Lower Risk

Risk Assessment: High

Immediate Market Impact or Slow Burn?: Immediate Market Impact

Unpredictability is part of Trump’s MO and he is capable of deploying it very effectively. But while unpredictability can be powerful when negotiating, it can create a difficult environment for businesses. Companies put a lot of capital at risk based on expectations of future profits, and generally want policy clarity. (Also note that there are ways in which the Trump administration is making it easier to do business, but the focus here is risks.) Initially viewed as a small risk, it’s clear uncertainty around some policies has weighed on business sentiment. Every policy environment has its element of unpredictability. With the last Trump administration, for example, we did see tariff policy uncertainty weigh on business investment, which put a dent in the expected positive supply-side impact of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. We think the risk now is higher and has put a damper on the “animal spirits” we might have seen if there was a sharper focus on pro-growth policy.

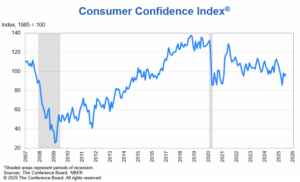

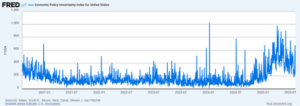

Note that policy uncertainty is not always a negative for markets because markets tend to be forward looking and uncertainty (fear) can be overpriced. High or peak uncertainty can often occur near market lows—this in fact what we saw just after Liberation Day. We can see the decline in policy uncertainty in the Economic Policy Uncertainty Index shared by the Fed, which has been trending downward since early April, but remains above its longer-term baseline.

Risk 4: DOGE Inadvertently Breaks Something

Change since March 26: Lower Risk

Risk Assessment: Low

Immediate Market Impact or Slow Burn?: Slow Burn

DOGE hasn’t gone away, but Elon Musk has and aggressively cutting the federal government’s workforce has at least slowed (and in some cases even reversed). From a market perspective, it’s hard to gauge the economic impact (and eventual market impact) of DOGE. While some cuts have been dramatic, given the scale of an entire economy it’s really the knock-on effects that would cause a true economic disruption, and the chances of that happening at a scale large enough to have an effect on markets has fallen. The aggressive cuts did introduce “known unknowns” that require some caution and add to the general environment of policy uncertainty. But still, I’m inclined to say this one is almost off the table at this point.

Risk 5: Internal Division within the Republican Party Delays or Limits Policy Implementation

Change since March 26: Much lower risk

Risk Assessment: Resolved and now an opportunity

The OBBBA was passed on an aggressive timeline despite internal divisions in the Republican party and narrow majorities. Ultimately, House Republicans worked through some ugly internal disputes to pass their version of the bill. Then Senate Republicans took over and made the bill more moderate (and more expensive!) and used some porcine persuasion to get it across the finish line, knowing that the House would likely be forced to just pass the Senate version if Republicans wanted to meet their timeline. (That’s part of the advantage of the Senate going second.)

As we’ve highlighted many times, an increase in deficit-financed government spending, whatever long-term challenges it brings, flows through to business profits. This isn’t speculative—it’s a national accounting identity. (See Sonu’s “How Will the One, Big, Beautiful Tax Bill Impact Markets.”) The OBBBA will have a smaller impact than the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, in part because a big piece is simply to extend provisions from the TCJA that would have sunsetted. Taxes raised via tariffs, which are correspondingly negative for profits, will also offset some of the effect. Nevertheless, this risk is off the table.

Risk 6: Immigration Policy Stunts Economic Growth

Change Since March 26: Somewhat higher

Risk Assessment: Moderate

Immediate Market Impact or Slow Burn?: Very Slow Burn

In my view, this is the most underrated risk but still secondary to those listed above it when it comes to the absolute level of risk. Clearly there are some genuine problems with current immigration policy. But the extent to which the resilience of the US economy depends on its ability to attract and absorb global labor is often underestimated. In fact, I would say the two key factors that have led to the structural advantage the US has over other developed economies is a more business-friendly overall policy environment, including labor market flexibility, and its history of acting as a destination of choice for global labor.

It’s hard to determine the level at which tighter immigration policy becomes a genuine risk, and before it becomes a risk there certainly may be areas where reforms would provide benefits. The aim here is not to determine what the right immigration policy should be, but just to highlight that at some point tight policy can start to impact the economy and markets.

Net immigrant in-flows have fallen dramatically according to estimates from the San Francisco Federal Reserve. That will have an impact on job growth, (and probably explains why job growth has slowed as much as it has, and why revisions are large), but it will also lower the job growth needed to keep the unemployment rate steady because immigrants also contribute to unemployment. But even with a steadier unemployment rate, fewer jobs added will mean slower aggregate income growth, which is the primary driver of US economic growth.

Here are just a few of the reasons immigration policy could pose a risk from an economic perspective:

-If the current level of flow of earners falls due to immigration policy and the chilling effect on new immigration, there’s a direct impact on GDP. A dollar of lost income is a dollar of lost GDP. Policy that leads working immigrants to leave the US, or choose not to come in the first place, is the economic equivalent of exporting U.S. GDP growth to the rest of the world.

-There is a steep implicit regulatory burden on business from tight immigration policy, both by restricting their access to workers and making the cost of labor higher.

-A more restricted labor pool also has the potential to drive wages higher, posing some additional risk for inflation. This effect may be stronger with the prime age participation rate already near a record high. We think this risk is fairly small, but not non-existent.

Immigration reform is a positive goal, but also comes with some risks. How high those risks are depends on actual policy. It would take a fairly large mistake to have enough of an impact on the economy to weigh on markets, but the potential for a large mistake is non-trivial. Nevertheless, the effect here is more likely to be slower (and long lasting) and in the near term more concentrated in certain industries.

Risk 7: Fed Independence

Change Since March 26: Unchanged

Risk Assessment: Low

Immediate Market Impact or Slow Burn?: Immediate if it were to occur

I would consider this a very small risk, but with the consequences of a misstep potentially large. The war of words has escalated, but I don’t think the actual risk has. Trump continues to put pressure o the Fed to lower rates, and initial restraint by the president has given way to a much more aggressive stance. But comments on Fed policy in and of itself isn’t a problem. There are mechanisms that help maintain Fed independence. But if there is an effort to overstep or to appoint a loyal and partisan Fed chair when Jerome Powell (himself a Trump appointee) steps down in May 2026, markets will respond. This one is unlikely to be a slow burn. If Trump oversteps, I would expect the market response to be unmistakable. (In fact, it already has been when threats have escalated.) But if Trump floats test balloons that cause market jitters that can easily be stepped back, it’s not an issue. But a genuine threat to Fed independence that cannot be walked back could be a problem. This may also arise through efforts to call into question the constitutionality of independent agencies, which is a potential stepping stone to removing Fed independence.

Interestingly, Fed policy (although not necessarily Fed independence) is a place where Trump’s inclination (lower rates) is most directly in conflict with Project 2025, which wanted more emphasis on the inflation side of the Fed’s dual mandate and in fact recommended removing the “maximum employment” mandate altogether. There are other areas where they are more aligned, including potentially limiting Fed independence, but I would characterize Project 2025 as generally hawkish on Fed policy while Trump is quite dovish, especially when he’s in office.

Where does that put us 1/8th into the second Trump administration? There is always potential for a policy mistake under any administration, or a monetary policy mistake by the Fed for that matter. Even from a non-partisan perspective, there were policy mistakes during the Obama and Biden administrations and the point isn’t to gauge whose policy is the most precarious but just to point out the current vulnerabilities. It’s fair to say the risks now are probably more consequential because President Trump is trying to more fundamentally reshape the government and the economy. And we have clearly seen some negative economic consequences from policy (the White House and the Fed), even if it might be the initial investment to get to the next step. But up to now the cost has been market volatility, not market gains. The margin of error has narrowed, but with some risks off the table, our base case remains that markets can power through over the rest of 2025.

8256607.1 08.06.25A

For more content by Barry Gilbert, VP, Asset Allocation Strategist click here