The Fed left policy rates unchanged in the 3.50-3.75% range at their January meeting, as expected. This is the first pause in four meetings, as they cut 0.75%-points over their last three meetings in 2025.

The official statement nodded to an improved labor market with lower downside risk to employment. That may seem like a big shift from their last meeting, which was just six weeks ago, when they were worried enough to lower rates for the third consecutive meeting. But since then, we’ve received two payroll reports showing the unemployment rate fell from 4.6% to 4.4%. Payroll growth over the last two months (November and December) averaged 53,000 per month, not great, but possibly enough to keep up with population growth, given the collapse in immigration.

The Fed’s view, underlined by Fed Chair Jerome Powell in his press conference, is that upside risks to inflation and downside risks to employment have diminished, which is why it believes policy is well-positioned right now, especially after the three recent cuts to protect the labor market.

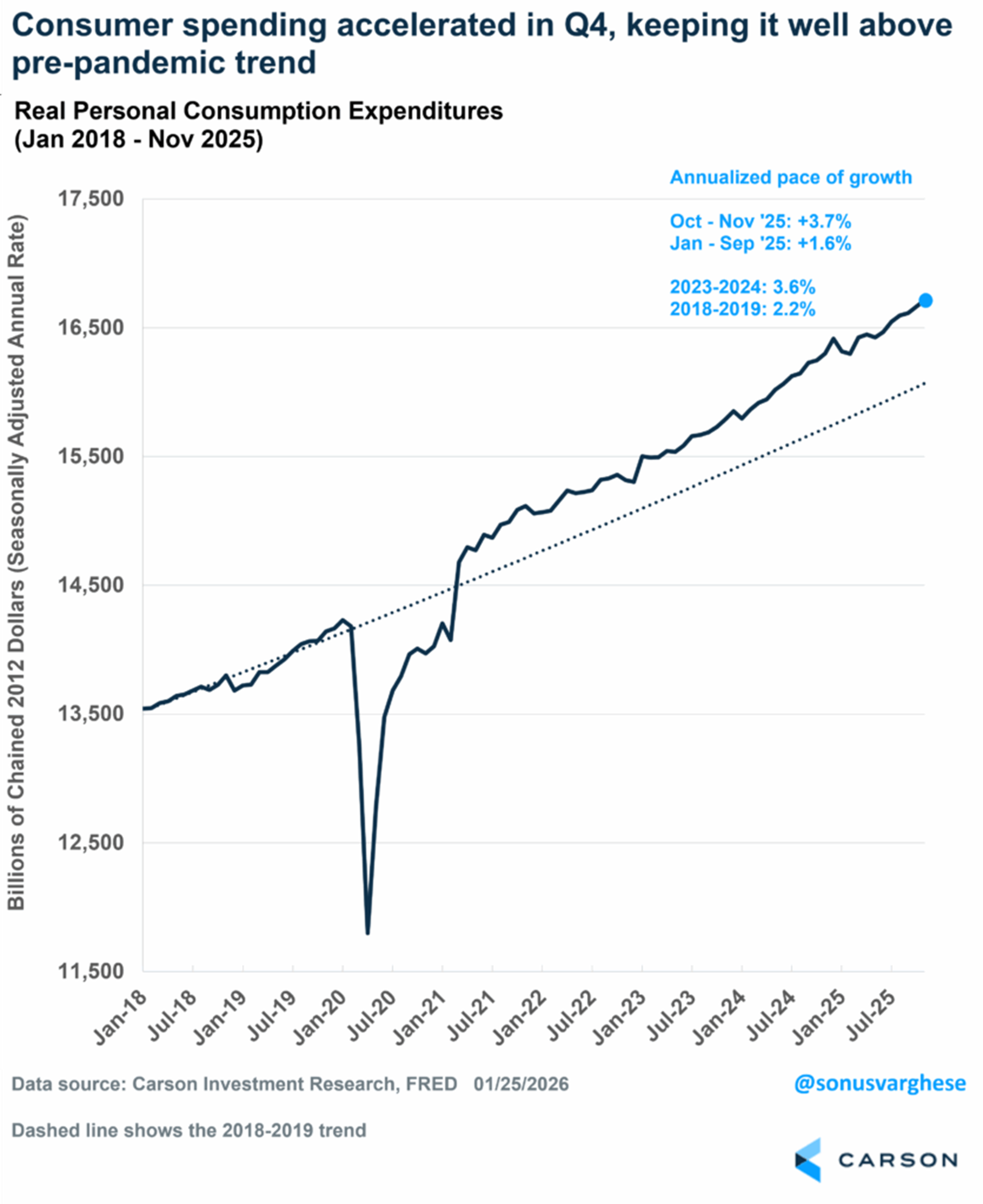

The Fed notably had a much more positive outlook for the economy, a marked shift from six weeks ago. That’s because recent consumer spending data has been solid. Inflation-adjusted “real” personal consumption rose at an annualized pace of 3.7% over the most recent two months for which we have data (October and November).

- That’s well above the 1.6% pace we saw over the first nine months of 2025.

- The pace over those two months matches the red-hot pace we saw in 2023-2024.

- It’s also ahead of the pre-pandemic 2018-2019 pace of “only” 2.2%, and that was pretty good.

Moreover, Powell noted that the pickup in consumer spending occurred even before financial conditions began easing (due to their rate cuts and higher stock prices) and before fiscal easing in 2026 (due to tax cuts). We believe the economy is also likely to continue benefiting from the AI investment buildout.

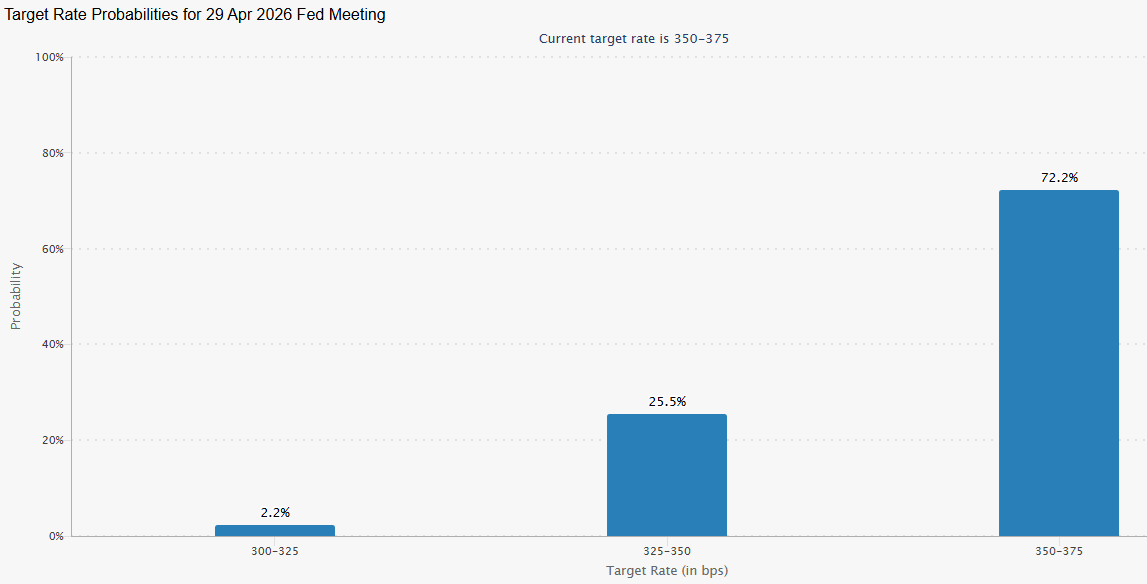

So, 2026 is “starting off on a solid footing.” Even more than the pullback in the unemployment rate, which is welcome, I believe it’s this improved economic outlook that led the Fed to pause. And unless we see renewed softening in the labor market, I don’t think the Fed is going to cut rates again until June. In fact, markets are currently pricing just a 28% probability that the Fed will cut rates at least once across its next two meetings (in March and April).

From June, it’s a different story, mostly because Powell’s term as chair ends on May 15. For now, investors are pricing in two more rate cuts in 2026, including one as early as June.

But there’s still a lot of uncertainty beyond that for the path of policy rates, not least because of uncertainty around who will replace Powell.

Who Will Be the Last Man Standing?

One thing I was curious about going into the Fed meeting was how many dissents we would see in favor of cutting rates. It would tell us two things:

- Whether Fed Governor Chris Waller is still interested in the Fed Chair position

- How easy or hard it will be for the next Fed chair to wrangle the committee into cutting rates more aggressively

As it turns out, the decision was 10-2, with dissents from Governors Chris Waller and Stephen Miran. Miran’s position is not a surprise. He is temporarily “on loan” from the White House (he was the head of the Council of Economic Advisors) and has been advocating for a slew of rate cuts, including a dissent back in December in which he preferred a 0.5% cut to the 0.25% we saw.

Waller’s dissent is more interesting. He agreed with the 0.25% cut in December and dissented in favor of another cut at this meeting. I don’t doubt that he thinks the Fed should be easing policy further to protect the labor market, but this dissent does improve his chances in the horse race for the Fed Chair, especially since President Trump is looking for someone amenable to rate cuts.

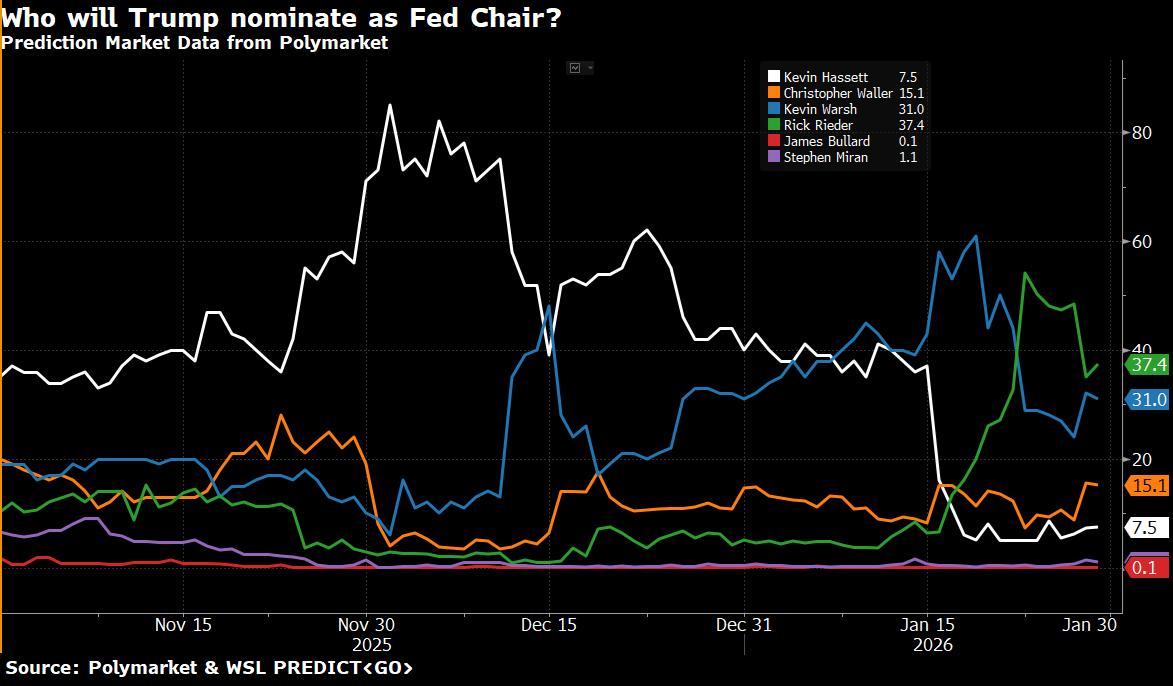

Waller’s chances in prediction markets rose after the dissent, from under 10% to 15%. This came mostly at the expense of this week’s “most talked about” candidate, Rick Rieder, BlackRock CIO of global fixed income, whose odds fell from 48% to 37%. The prior week’s favorite, Kevin Warsh, saw odds improve from 24% to 31%, though he was at 61% two weeks ago. Meanwhile, the odds-on favorite from a month ago, Kevin Hassett (current head of the National Economic Council in the White House), is at just 8%.

It’s notable that no candidate is over 50%, which means prediction markets haven’t coalesced around a likely pick yet, so it’s not as if the collective wisdom of prediction markets is really providing any meaningful insight. Really, the choice comes down to one person, President Trump. And the fact that even the odds of the person who was at almost 90% a couple of months ago (Hassett) collapsed may indicate that Trump isn’t happy with his current options. Hence, the volatility in betting markets.

The reality is that Trump likely wants someone he can trust to reduce rates significantly, perhaps all the way down to 1%, or at make an unrelenting effort with every tool available. At the same time, he doesn’t want his pick to cause an adverse market reaction, one of his favorite gauges of how he’s doing. The rub is he probably believes he was too deferential to markets (and conventional opinion) in his first term when he nominated Powell. Also, choosing someone more likely to impose Trump’s will, or at least try, has been characteristic of his second term appointments in general.

Here’s a rundown of the lead candidates:

- On the face of it, we believe Hassett would be the most likely to “toe the line,” but for whatever reason, Trump wants him where he is right now.

- Kevin Warsh has historically been an inflation hawk, even in 2008-2009, when it was clearly the wrong decision. While he’s making the right noises about reducing rates (for obvious reasons), his history doesn’t seem convincing.

- Chris Waller is probably the most likely candidate to convince the rest of the Fed to go along with rate cuts, but even he’s unlikely to take rates much lower than they are now, which is obviously not enough for Trump.

- Rick Rieder, who is/was the dark horse candidate, has made comments about taking rates below 3% on the back of productivity growth (like Scott Bessent). However, the reality is that he’s also unlikely to push rates as low as Trump wants.

Hence, the continued large swings in prediction markets.

The Path After June Is Uncertain, as the Math Gets Hard

The fact that the Fed’s rate-setting committee was broadly in favor of holding rates steady, with 10 of 12 members supporting that stance, is also notable. That makes us believe that, unless the labor market softens again and economic growth hits the skids, it’s going to be difficult to get these folks to move forward with rate cuts. That means the new Fed chair will be hard-pressed to find votes to cut rates further.

Assuming Powell is replaced by someone in favor of rate cuts, that would take the number of votes in favor of cuts to three (assuming Waller remains in favor of cuts if he isn’t chosen as chair). If the administration is successful in kicking out Governor Lisa Cook for “mortgage fraud” (though the Supreme Court appears skeptical of the administration’s arguments), that would be one more vote in favor of cuts, taking it to four. But getting a majority (7 of 12) in favor of cutting would require three more voting members to switch.

Moreover, Powell could throw a wrench into this process by choosing to stay on as Fed governor even after his term as chair ends (his term as a governor wouldn’t end until 2028). And chances are Powell has more sway over most of the committee members than a new Fed chair who comes in blazing as a champion of cuts would.

Of course, the economy could take a turn for the worse, and we could still get rate cuts, but that’s not our base case.

The 1990s May Not Be a Good Comparison

If the economy is doing well, the new Fed chair will likely argue that solid productivity growth will lead to lower inflation, allowing the Fed to drop rates further. Rieder, and even Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, have made this argument. They highlight that strong productivity is what “allowed” Greenspan to lower rates in the 1990s.

However, there are other important pieces in the 1990s story that don’t apply now—it wasn’t just productivity growth.

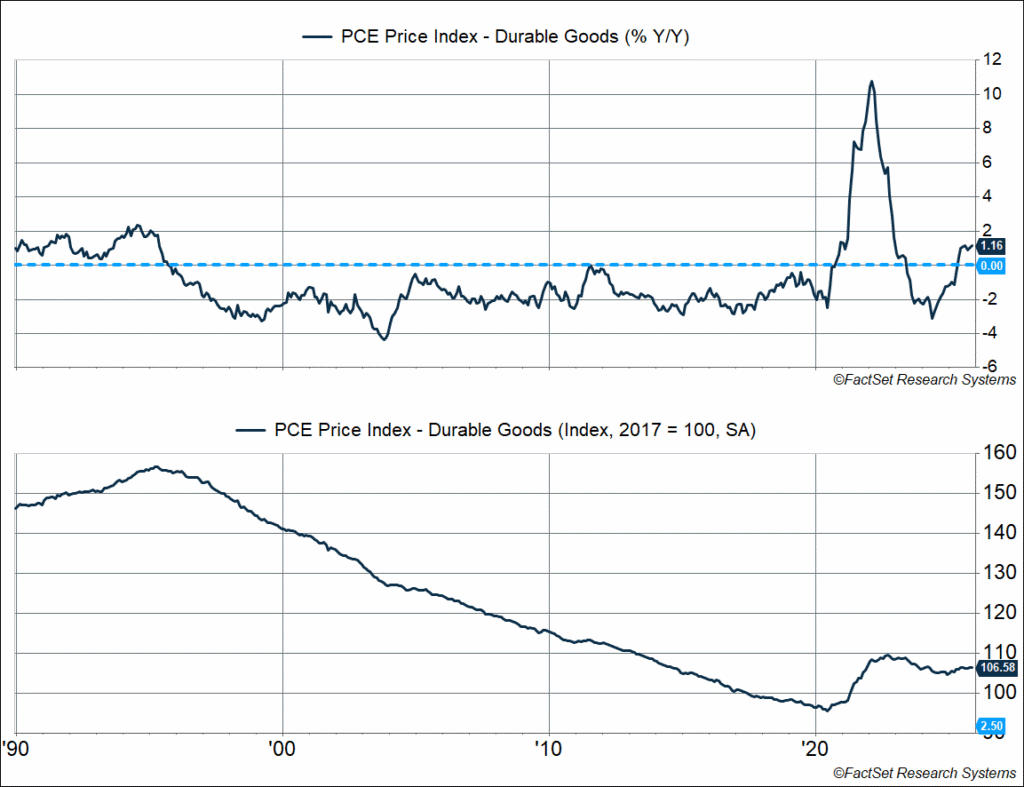

First, globalization took off after 1995, first with NAFTA coming into effect and then with China entering the WTO in 1999. You can see what happened by looking at durable goods inflation. Prices were increasing at a 1-2% annual pace in the early 1990s, before starting to fall post-NAFTA. In fact, inflation for durable goods collapsed and remained below zero (that is, prices consistently fell) all the way through 2021! It only paused when we got the post-Covid inflation surge in 2021-2023 and then again with tariff policy in 2025. While hard to see directly, there was a massive dividend from the much-maligned free trade agreement, expressed indirectly through “affordability.”

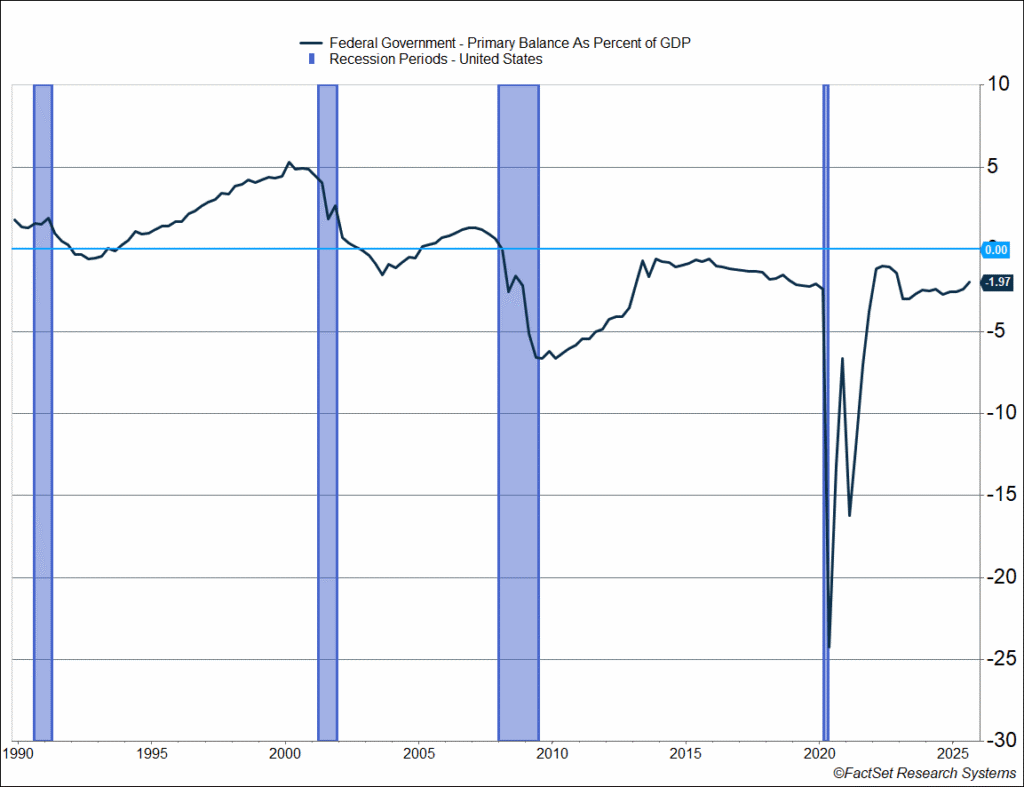

An added factor in the low inflation of the late 90s was the federal government running a primary surplus from 1995 onwards. The primary balance is the fiscal balance excluding interest payments, and it’s a good way to get a sense of actual fiscal outlays that are passed by DC lawmakers relative to revenue. As you can see below, the primary balance moved into surplus in 1994 and was running around 3-5% of GDP in the late 1990s. That kept a tight lid on inflation.

Right now, neither of the above conditions holds.

- Globalization is reversing, and we probably won’t see goods prices fall consistently as they did from 1996-2020. Instead, we’re likely to see more volatile inflation for goods, especially as the tariff mess continues.

- The fiscal primary balance is running at a deficit of 2% of GDP right now. It improved a bit in 2025 but is likely to worsen in 2026 as the tax cuts come into effect. This may put upward pressure on inflation, especially since inflation is already elevated.

Productivity may still run strong, as it did in 2025, but as we saw last year, that doesn’t mean inflation will ease.

This Is Why Gold Is Surging

In a normal environment with inflation running where it is right now, we’d likely see:

- A move toward smaller fiscal deficits, if not primary surpluses

- Higher interest rates

We have neither right now. As I noted above, fiscal deficits are likely to get worse this year, and the Fed is under pressure to lower rates further, even though the inflation outlook looks quite messy (see commodity prices for one thing). This backdrop creates a risk of currency debasement, and gold has been a very obvious beneficiary.

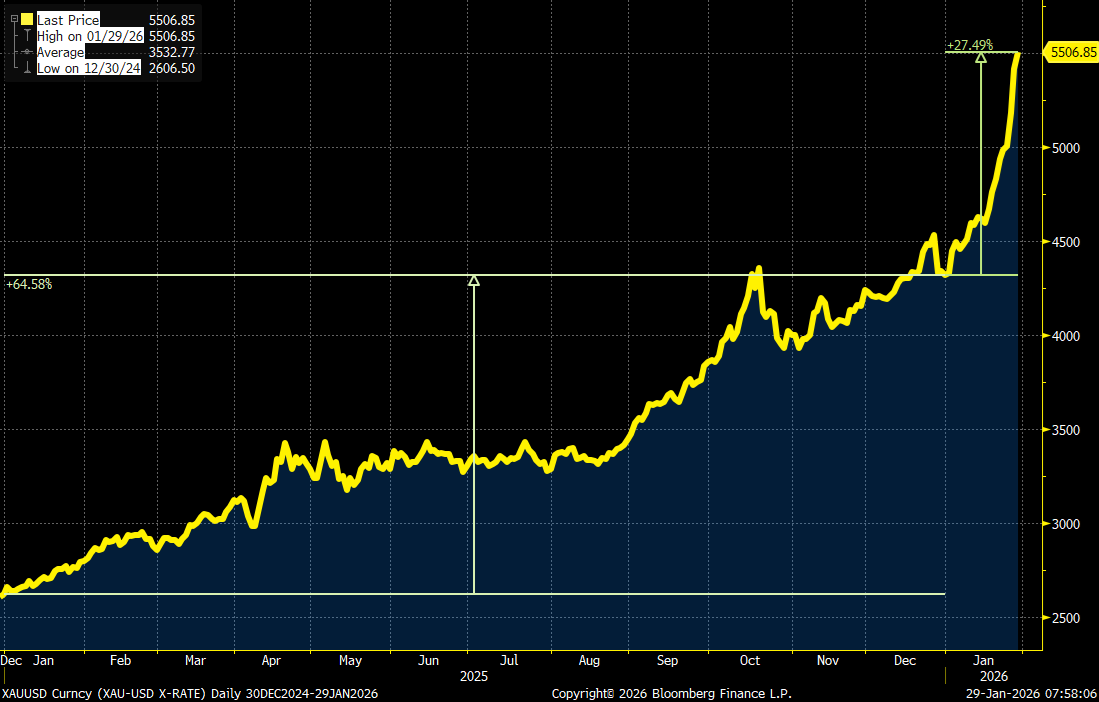

The debasement trade is essentially why gold is surging. In fact, it’s risen 28% year to date, and that’s on the back of a 65% gain in 2025.

What could end the rally? Simply put, it would be a reversal of the current dynamic:

- A move by Congress (and the White House) to pull back fiscal spending and cut the deficit in a significant way

- A much more hawkish Fed, especially one that may look to hike rates to crush inflation once and for all, a la Volcker in 1980-82

This is obviously unlikely to happen anytime soon, which means we believe the debasement trade is likely to continue apace. We think that would support gold powering even higher (which is not to say we won’t see volatility).

Ryan and I talked about all this on our latest episode of Facts vs Feelings—take a listen below.

Link to the latest episode:

For more content by Sonu Varghese, VP, Global Macro Strategist click here.

8744735.1. – 29JAN26A