It’s been a while since we got any macroeconomic data thanks to the government shutdown. The most recent official payroll report for September was released a couple of weeks ago, and it showed that the unemployment rate continues to move higher, hitting 4.44% in September. While other data, like initial claims for unemployment benefits, points to a relatively low level of layoffs, a rising unemployment rate indicates that labor market risks are rising. Once the unemployment rate starts to move up, it takes on momentum that can be hard to reverse, even if the Federal Reserve reacts with a slew of rate cuts. That’s why in an ideal scenario, the Fed would be staving off a further rise in unemployment by easing policy sooner rather than later.

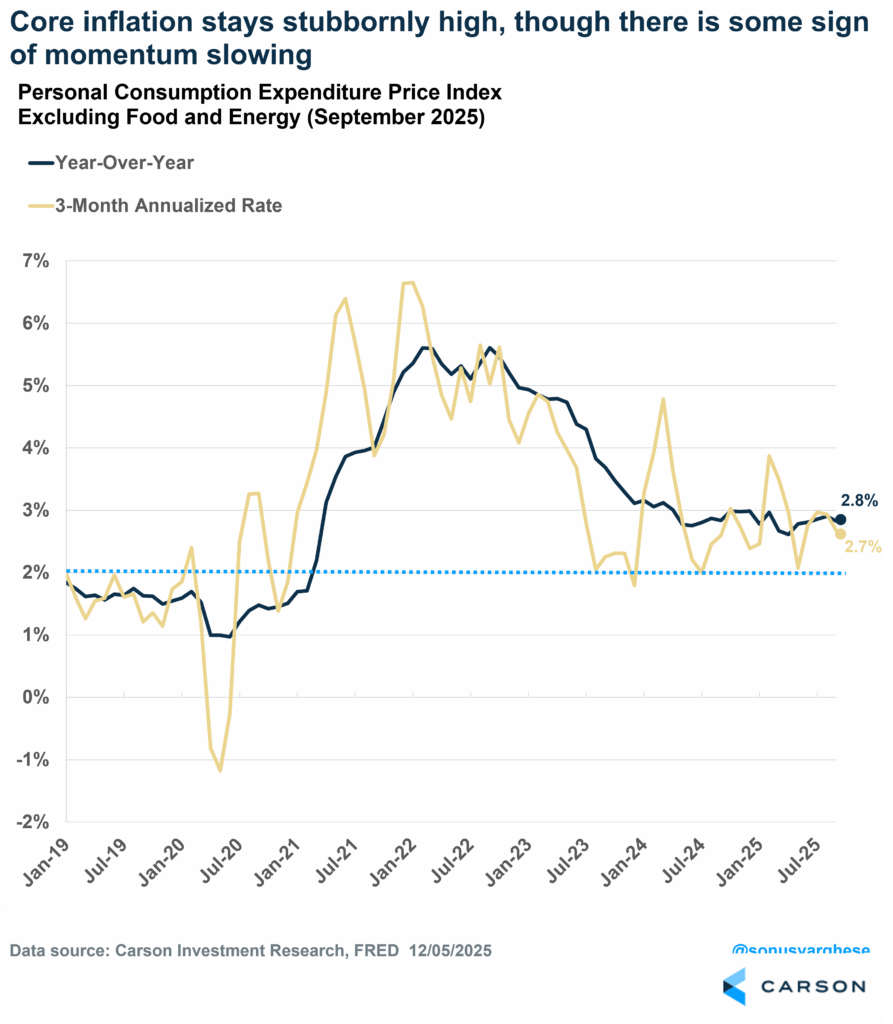

The problem right now is that inflation is running above the Fed’s 2% target. The Fed’s preferred inflation metric, core personal consumption expenditures inflation (that is, excluding food and energy ) or “core PCE” has been sitting above 2.6% for four and half years now (54 months). It’s come down from a peak of 5.6% (in early 2022) but over the past year it has stayed stubbornly high, in a range of 2.6–3.0%.

But there is a slight glimmer of hope in the data that the government just released, even if it is data from September due to the shutdown. Core PCE rose just 0.2% in September (equivalent to an annualized pace of 2.4%). Over the last three months of the period (July–September), core PCE ran at an annualized pace of 2.7%, a slowdown from the 2.9% pace in August and 3.0% in July. But over the past year, core PCE is still up 2.8%.

You kind of have to squint to see momentum slowing, but the Fed will take breathing room where they can get it. And this more or less locks in another 0.25%-point rate cut at the Fed’s meeting this week, taking the policy rate to the 3.5–3.75% range. Fed funds futures currently price the probability of a rate cut at 87%, indicating investors also believe a rate cut is coming.

Source: CME FedWatch Tool – CME Group. (n.d.). Www.cmegroup.com.

There’s a reason the probability of a rate cut at the Fed’s December meeting is not closer to 100%, and that gets to the angst several members have about cutting rates while inflation remains well above the Fed’s target.

Up until last year, inflation was elevated because of lags in official shelter inflation data, where official data had yet to capture the real-time dynamic of easing rents. However, that’s switched this year and we’re starting to see shelter disinflation. Yet, inflation still remains elevated, and that gets to two other sources of inflation.

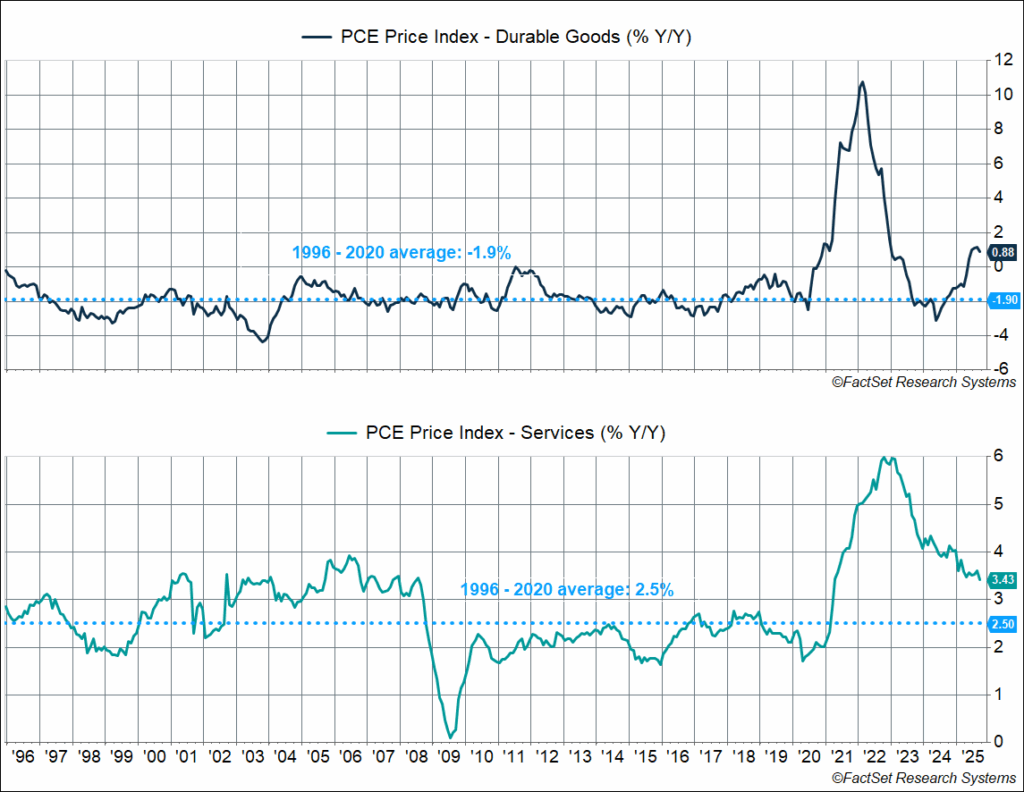

The first is durable goods inflation which is up 0.9% year over year as a direct result of tariffs. Now that reading doesn’t seem like a lot but at the end of 2024, inflation for durable goods was running at -1.3%, so we’ve had a big swing to the positive side. Moreover, the current positive inflation reading for durable goods is outside the norm of what we’ve seen in recent history (outside of the supply-chain induced issues in 2021–2022). From 1996–2020, inflation for durable goods averaged -1.9%, that is, at least in this category, prices were actually consistently falling. In fact, the highest reading it ever got to over that period was -0.2% year over year in August 2011. So the current level of inflation we’re seeing for durable goods, while relatively low, is outside the “norm.”

The second reason is that we’re actually seeing elevated levels of services inflation as well. It’s currently running at 3.4% year over year, despite the slowdown in housing inflation. That would be okay if we were seeing goods prices fall at the same time, which would be more similar to the dynamic we saw in the mid-2000s, when services inflation was relatively elevated above 3%, but it was offset by goods deflation.

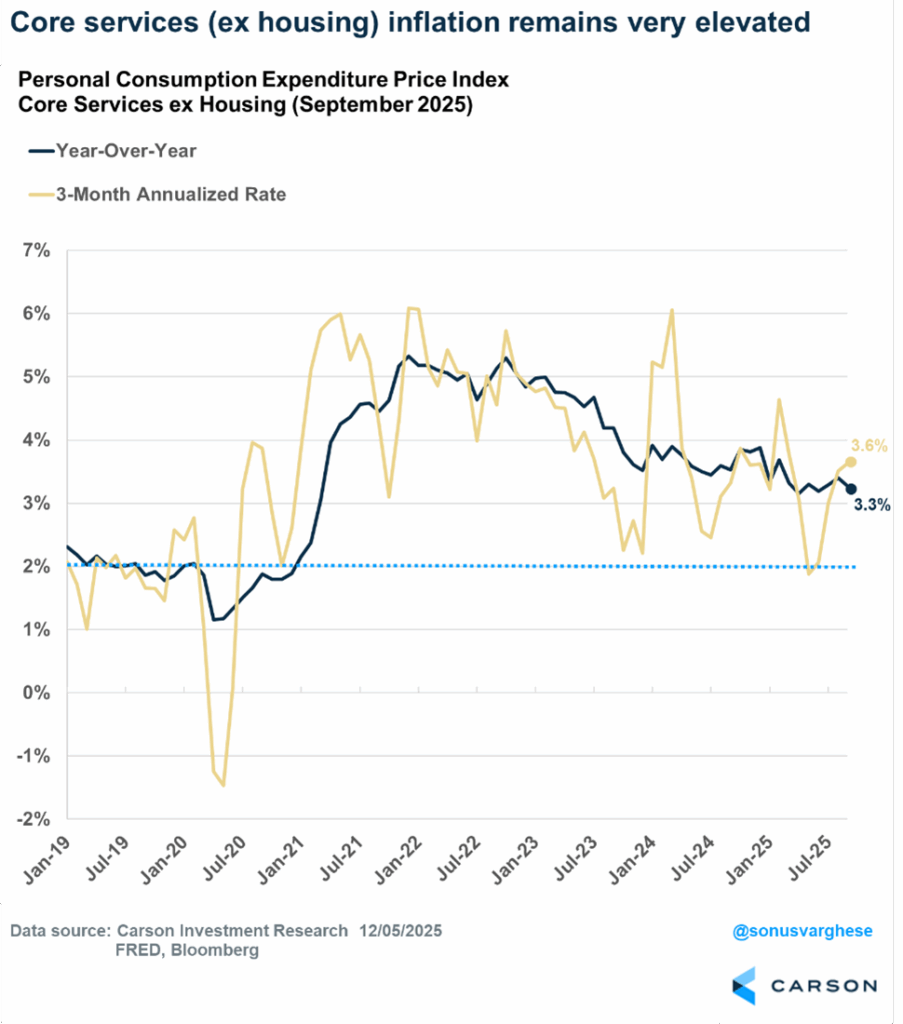

In fact, if you exclude housing, the PCE index for services ex housing is running at an elevated 3.6% annualized pace for the three months through September. That’s going in the wrong direction. The year-over-year pace is 3.3% and has remained stubbornly elevated for a few years now.

All this to say, there’s a reason why there’s angst amongst Fed members to cut rates. Still, we believe the majority of the committee will prioritize protecting the labor market (while focusing on the positives of inflation data, like shelter disinflation) and cut rates in December. Moreover, in 2026, President Trump is likely to pick a new Fed Chair who is more amenable to continuing to cut rates (Chair Powell’s term runs out in May 2026). That could be positive for the economy, let alone the stock market.

For more content by Sonu Varghese, VP, Global Macro Strategist click here.

8654101.1. – 8DEC25A