Two years ago, when we were writing our 2024 Outlook, we decided to call it Seeing Eye to Eye, with bit of a pun on “AI to AI.” We knew then that the AI impact was coming but also knew we were in early days. In fact, we expected relatively little direct impact on the economy in 2024 at all. Well, here we are, just two years later, and there’s been so much chatter about the “AI Bubble” that I’ve seen articles on the “bubble in articles about the AI bubble.”

The question isn’t really whether we’re in a bubble. It’s such a vague term that whether we’ll be talking about an “AI bubble” in 10 years can only be known in hindsight. The real question is how long the current trend in AI spending will last and how bad the fallout will be when it ends. What’s clear right now is that something massive is happening in the economy and it’s useful to understand the dynamics behind that, and the potential risks.

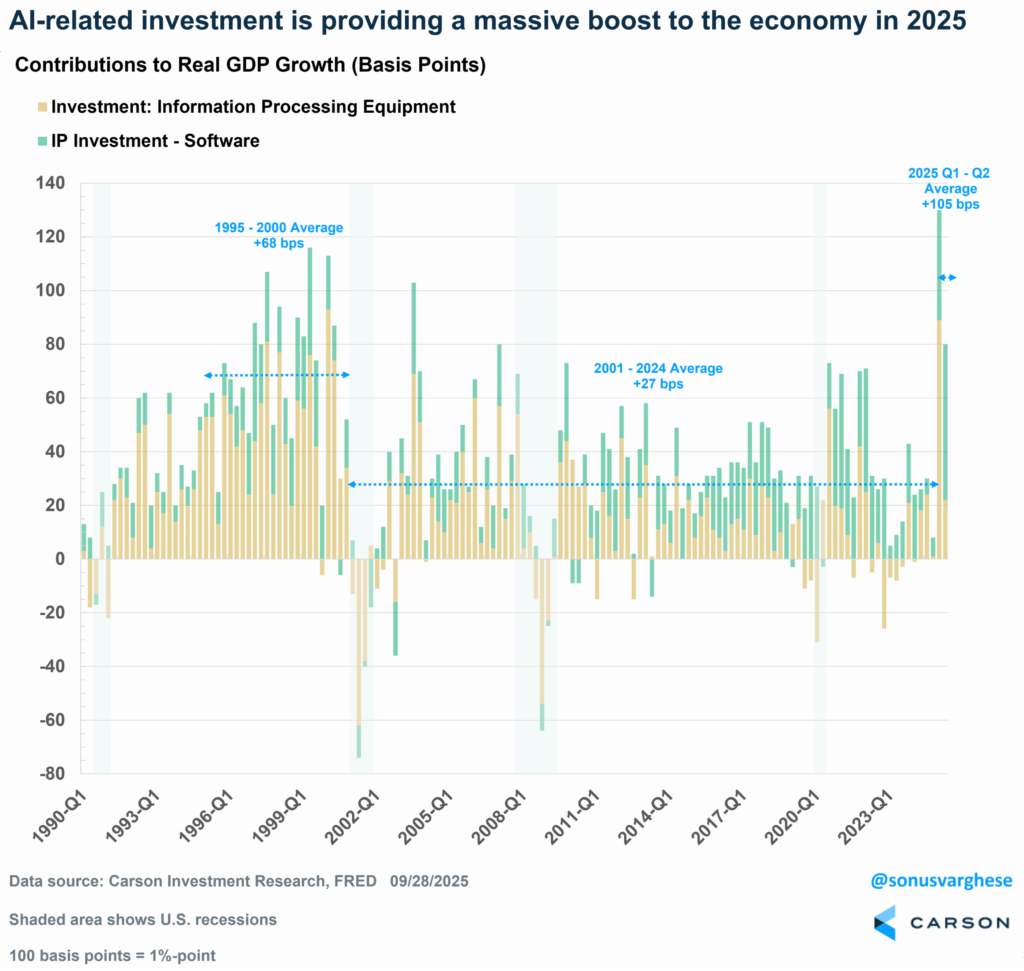

You generally hear about how AI is going to impact businesses, and the economy, in a big way soon. Here’s the thing: AI is already having a massive impact on the economy, especially investment (spending on AI-related hardware and software). In real (inflation-adjusted) terms, these contributed an average of 1.05%-points (105 basis points or “bps”) across the first two quarters of 2025—exactly as much as consumer spending. Keep in mind consumer spending makes up 70% of the economy, versus about 4% for the AI-related investment categories. For perspective, here’s how investment in information processing equipment and software contributed to GDP across the mid-to-late 1990s dot-com bubble and the 24 years after that (2001-2024):

- 1995 – 2000: +68 bps average per quarter

- 2001 – 2024: +27 bps average per quarter

Some of the strength in equipment spending in the first half of 2025 was likely a result of companies front-running tariffs (since a lot of it is imported), but that still leaves really strong software spending.

One Company’s Spending Is Another Company’s Revenue (and Profits)

As I’ve described in the past, private sector investment is a key source of corporate profit growth (in addition to government deficits and lower consumer savings). Since profits are the main driver for stock prices, the key question is whether this level of investment spending will continue. The short answer seems to be yes, and it looks like early innings on that front.

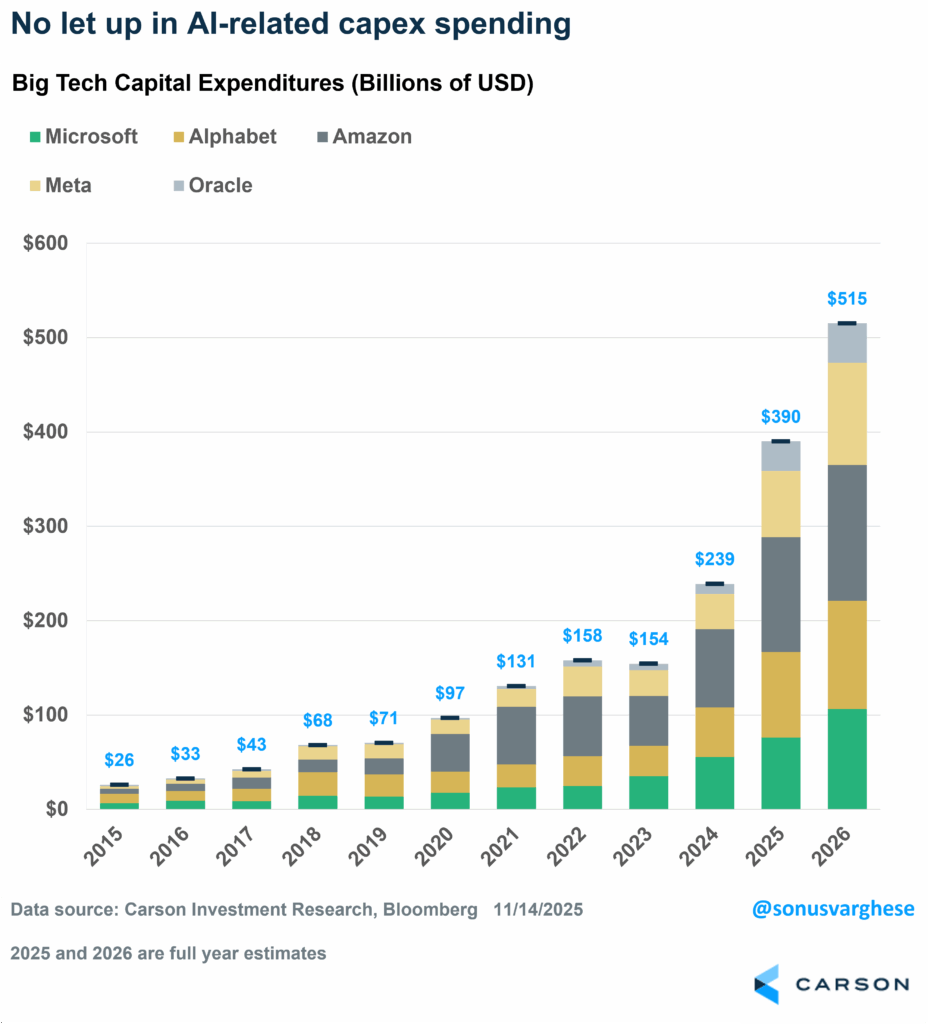

AI-related capital expenditures (capex) are being driven by the large tech companies, especially those that provide large-scale cloud compute capacity and operate hyperscale-level data centers (Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, Oracle). As the chart below shows, total capex is expected to clock in at almost $400 billion in 2025, up from $239 billion in 2024. Next year it’s expected to increase to $515 billion.

To be clear, these are staggering sums of capex. 2025 capex is running around 1.3% of GDP, more than double the 0.5% in 2023 and over 4x the size of where it was in 2019 (0.3%). It’s expected to increase to around 1.6% of GDP in 2026.

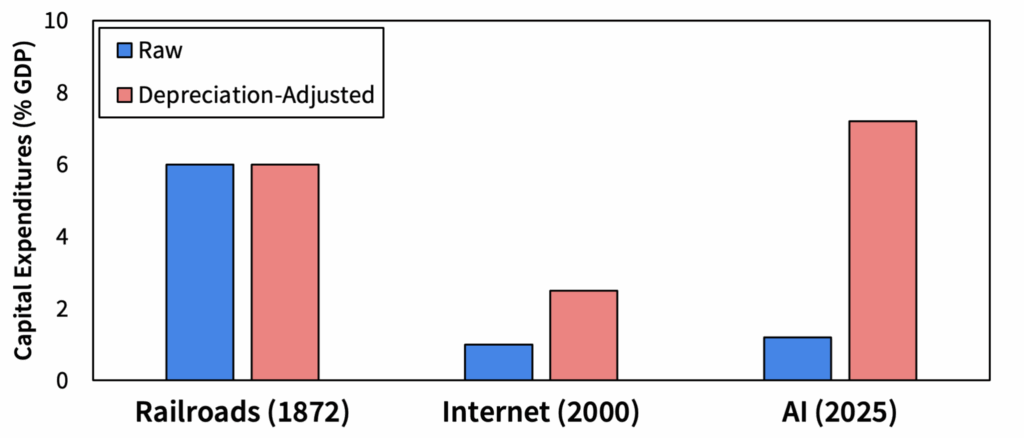

Our friend Kai Wu (at Sparkline Capital) recently wrote a very informative paper on the AI boom. He looked at previous historical periods in which private firms made massive capital outlays to build infrastructure underpinning a transformative technology—railroads in the 1870s and the internet in the late 1990s. The railroad boom began after the Civil War, with over 33,000 miles of tracks laid down from 1869 to 1873. Relative to GDP, the current AI capex boom is already larger than the peak of the internet boom. It’s still below the peak of the railroad buildout. However, the useful life of chips is much shorter than that of railroads, or even fiber optic cables. After adjusting for depreciation, the current AI buildout tops the chart below. Chips will have to be replaced relatively frequently because of improving technology, while railroad tracks are much more durable.

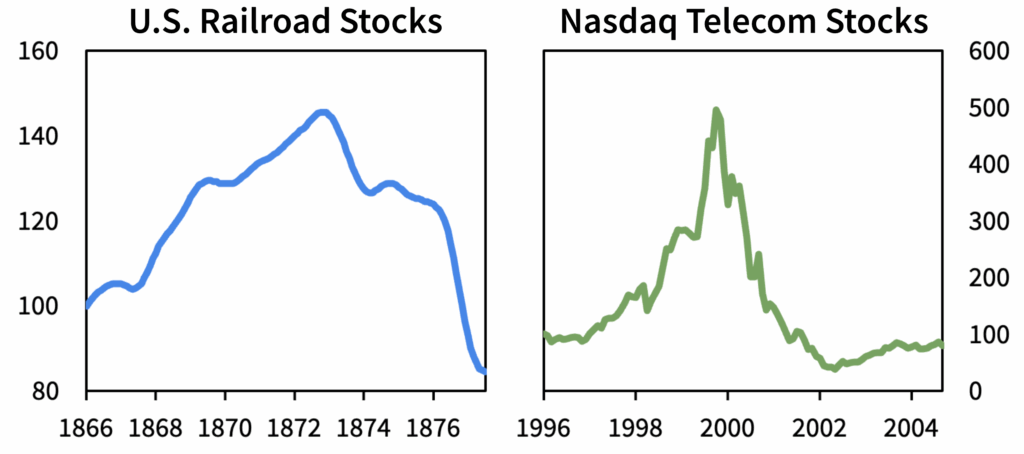

You don’t have to be a student of history to know what happened with the railroad and internet booms. Railroad stocks rose about 50% before collapsing. Telecom stocks rose 400% in the late 1990s before crashing.

The dynamics are similar across these booms. The promise of new technology pushes firms to make massive investments. Investors like that, and stock prices soar, facilitating even more investment. But ultimately, demand fails to keep up and there’s excess supply (which ultimately benefits society, whether it was railroads or high-speed internet that allowed us to stream cat videos). Over-capacity leads to lower prices and lower valuations, and investment spending reverses. The dynamic is exacerbated when debt enters the picture, as the unwind becomes ugly.

The big tech companies are massive cash-flow generating machines, with huge moats (protection from competition, but here especially new entrants) of their own. But they’re in a bind. Each one sees an existential need to “win” the AI race, and so they’re incentivized to ramp up investment. If one starts down that path, others feel the need to join the race and go all-in, which is why Google co-founder, Larry Page, said “I’m willing to go bankrupt rather than lose this race.”

Of course, this also brings us to the question about financing. After all, AI is a very capital-intensive business (whereas the tech companies’ current business lines are capital light). Right now, what we are seeing is a set of circular arrangements between the hyperscalers (big tech firms mentioned above), Nvidia, and OpenAI (who perhaps started everyone down this path in late 2022 when they released ChatGPT). The tech firms provide the investments but also gain a large customer (OpenAI), as does Nvidia (who gets to sell their chips). Investors react positively to these partnership announcements, bidding up stocks of:

- Chipmakers: in anticipation of continued AI demand

- Hyperscalers: in anticipation of AI-driven cloud profits

- OpenAI: in anticipation of platform dominance

All this keeps the wheel turning, as I explained in a prior blog. Higher prices and valuations grease the wheels, allowing the funding of even more aggressive investments. Of course, if stock prices pull back sharply, and over a sustained period, that’s going to throw sand into all the gears. As I mentioned above, the big tech firms have a lot of cash flow, but the capital intensity of AI means they are also turning to debt financing to fund AI infrastructure. That means another corner of the market, namely private credit lenders and real estate trusts, are also tied to the AI boom. It’s still early days—the big tech companies have relatively low debt right now, which means there’s lot of room to ramp up leverage. These companies are finding creative ways to keep the debt off their books, also potential trouble down the road but not right now.

Who Wins? Portfolio Positioning

None of this implies that AI is a passing fad. On the contrary, it could have a significant impact on how society functions several years from now, whether in our daily lives or how businesses operate. But from an investment perspective, historical infrastructure booms start with a period of overinvestment and end with poor returns.

At the same time, while there’s a left tail risk (a crash), there’s also a right tail risk (missing out on a boom that could last a while). The most traditional ways to “protect a portfolio,” by buying insurance (put options) or outright shorting technology stocks, are likely to suffer from the fact that you will most likely get the timing wrong with potentially very large opportunity costs. As the saying goes, “the market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.”

It seems cliche to say this, but we believe the answer to avoiding a wipeout (amid the eventual bust, and who knows when it will be) is diversification. So “surf the wave,” that is don’t be under-exposed to the boom, but don’t go all in. Instead, diversify, which is also our answer to index concentration (the top 7 stocks making up 35% of the S&P 500).

The AI-infrastructure firms are concentrated in the technology and technology-adjacent sectors (like communication services and consumer discretionary). But if AI usage does become much more widespread, and boosts aggregate productivity, a lot more companies will benefit. Normally, exposure to smaller companies would be another way to diversify, but we believe there’s more opportunity outside the US than small and mid-cap companies in the US. Emerging economies, especially China, Taiwan, and South Korea, are likely to ride the AI-infrastructure wave but developed market economies may be primed to benefit from more widespread, and cheaper, AI-usage. As I noted in my prior blog, a pickup in global activity is a potential tailwind for markets in 2026, and to that end, diversifying outside the US is attractive from both portfolio risk-management perspective as well as an opportunistic play.

We remain overweight equities as we move into 2026 but are neutral on US vs international stocks. Within the US, we are overweight large cap stocks but barbell exposure to technology (and related areas) with diversified bets on areas within the industrials sector and even the low volatility factor. On the international side, we are overweight developed markets, and underweight emerging markets.

Ryan and I talked about some of the tailwinds for 2026 on our latest Facts vs Feelings episode. Take a listen below.

For more content by Sonu Varghese, VP, Global Macro Strategist click here

8610831.1.-17NOV25A