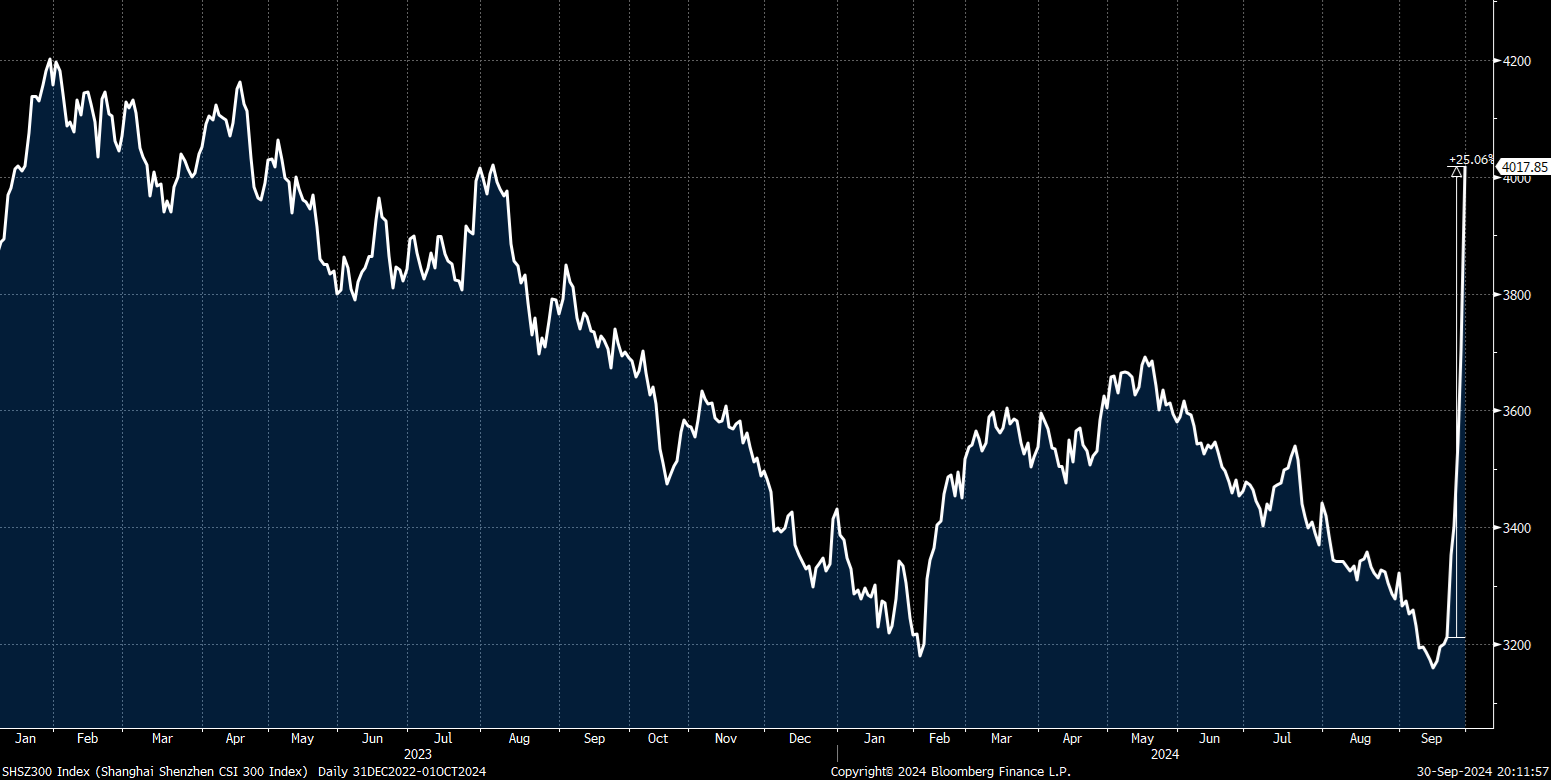

Chinese stocks have melted up over the past week, with Mainland China’s main index, the CSI 300, surging a whopping 25% since September 23rd (through the 30th). Just on Monday (September 30th), the index surged 8.5%, taking it to the highest level since August 2023. China’s markets will be closed for the rest of the week due to the Golden Week Holiday.

But here’s some perspective. Despite the surge, Chinese stocks still lag the S&P 500 by a lot over various lookback periods. Since the end of 2022, the CSI 300 is up 9% while the S&P 500 is up 54% (including dividends). Extending the horizon back to the end of 2019 (a quarter shy of five years), the CSI 300 is up 10% while the S&P 500 is up 92%. Pull it back to the end of 2014, almost a decade, and the CSI 300 is up 41% versus a massive 234% return for the S&P 500.

Panic Stimulus to the Rescue … Maybe

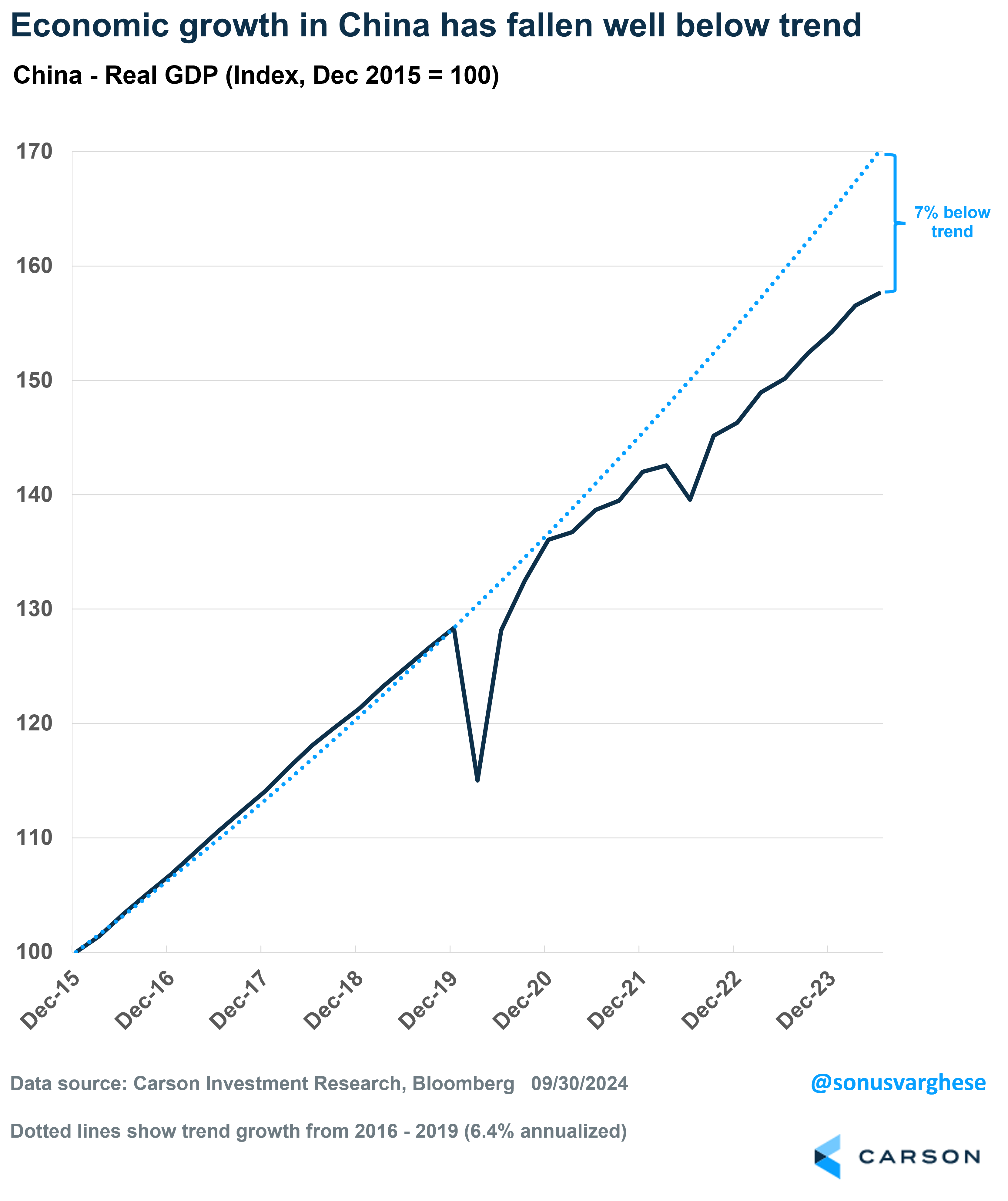

China’s central bank (the Peoples Bank of China, PBOC) announced a slew of measures to boost the economy, and markets, on September 24th. This was clearly an acknowledgment that economic growth is faltering. Consumption is running well below trend. Youth unemployment (ages 18-24) hit 18.8% in August (despite the statistical agencies changing the methodology to exclude students). Real estate activity, which is a backbone of the Chinese economy, is crashing, including construction activity, home sales, and home prices. Real GDP growth was up just 4.7% year over year as of Q2 2024, and on track to fall below the Chinese government’s 5% growth target for 2024 (the latest announcements suggest Q3 growth is not looking good). GDP growth is running well below the 2016-2019 trend of 6.5% annualized growth. Even that was a slowdown from the 7.5% annualized pace of growth from 2012-2015.

It was only a matter of time before stimulus was forthcoming, and there was much commentary over the past year as to when it would come. The only surprise was that it took as long as it did, and it was clearly panic. Amongst the stimulus measures announced:

- Cutting the benchmark policy rate

- Lowering the amount of cash that banks need to hold in reserve (to boost lending)

- Cutting interest rates on existing mortgages

- Lowering down payments for second homes

They also announced an offer of 500 billion yuan ($70 billion equivalent) in loans for funds, brokers, and insurers to buy Chinese stocks. No surprise that stocks melted up.

The PBOC has also said there’s more. Note that the PBOC is not really “independent” of the Chinese government (unlike the Federal Reserve here in the US). So, think of these measures as being pushed by the authorities in Beijing.

If you noticed, the measures were geared to boosting lending activity and the real estate sector. Regarding the latter, as I wrote earlier this year, real estate and related activities account for 25-30% of GDP, which is double the peak level we saw in Japan in the 1980s. Chinese authorities had already announced measures earlier this year to prop up real estate, but that’s not helped much. Real estate investment, which is key to watch, remains down 10% year over year as of August. This is partly because authorities themselves have tried to slow down the growth of bad debt in the sector, amid myriad issues with over-levered firms. Of course, that’s hit growth. Historically, property sector investment has come to the rescue of the Chinese economy when it was in trouble (2009-2011 and again in 2016). Hence the move to revive this growth engine.

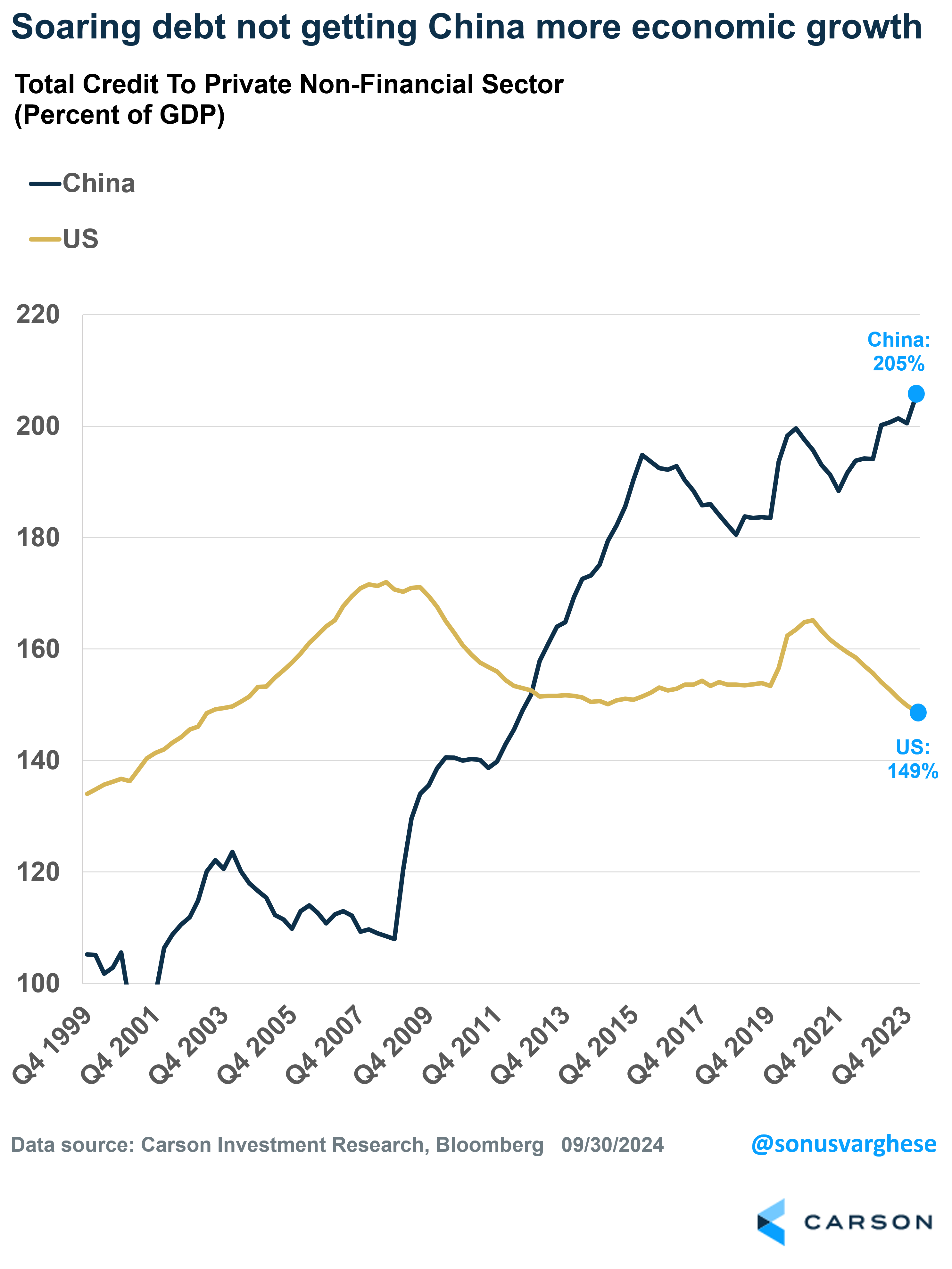

The problem with these stimulus measures is that Chinea’s problem is not really a lack of borrowing. As Michael Pettis, a Professor at Peking University and an expert on China’s economy, points out, the problem for Chinese businesses is not that banks are capital constrained to make new loans. The Chinese non-financial sector is heavily levered already. Credit to the non-financial private sector is running at 205% of GDP, compared to 149% of GDP here in the US. In fact, as you can see in the chart below, debt growth in the US is falling whereas it continues to rise in China. In other words, output is falling in China even as debt growth is increasing – which means the use of that debt is becoming less productive. As I said above, China’s problem is not that it can’t borrow easily enough.

What China Needs: Fiscal Stimulus for Households

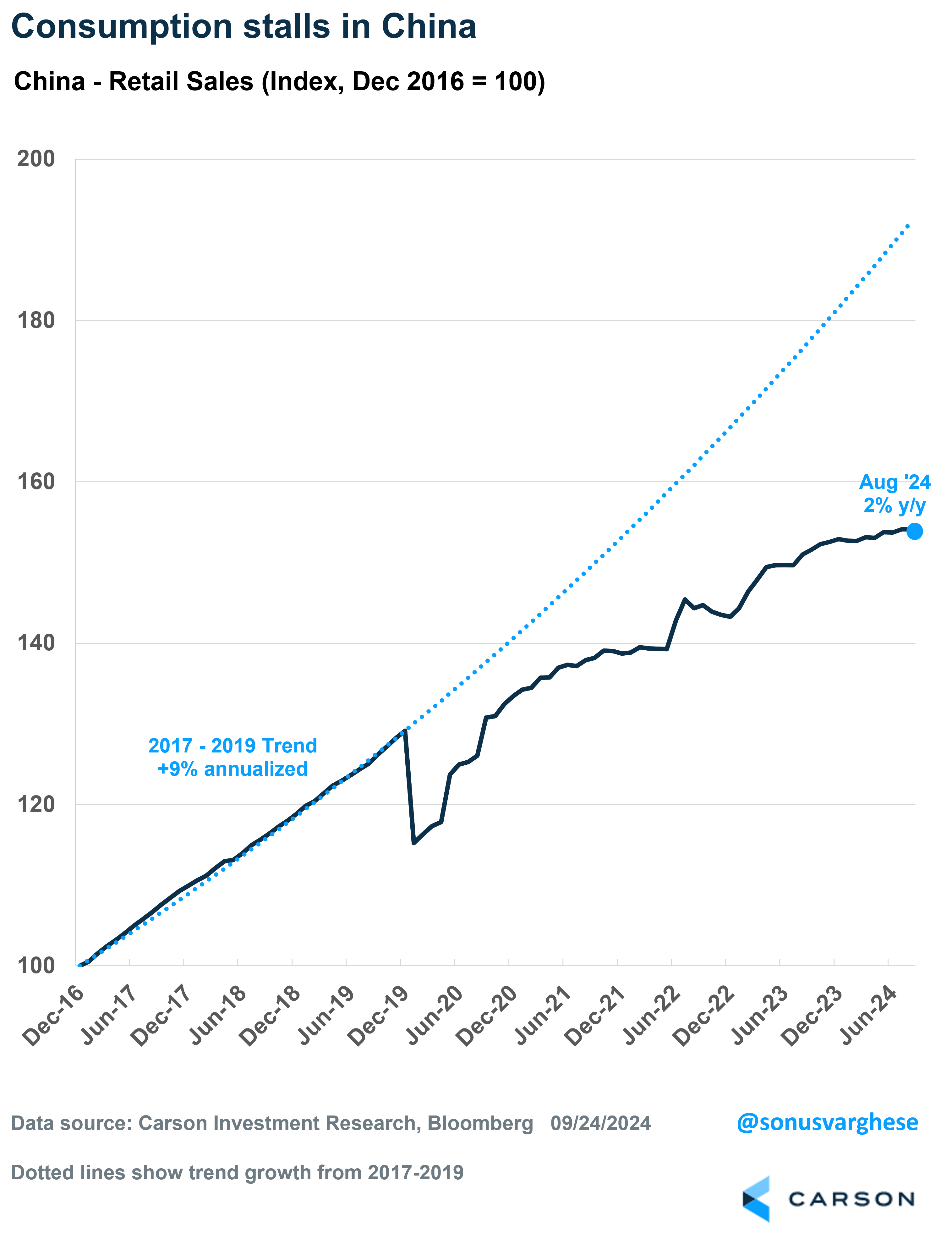

What China really needs is a fiscal stimulus package that ultimately redistributes income from the supply-side of the economy to households. Consumption was never the primary engine for growth in China, but it was still sizable. The problem is that consumption has seized up since the pandemic hit. Retail sales rose just 2% year over year as of August, versus a close to 9% annualized pace from 2017-2019.

Unlike the US, China never boosted households with stimulus measures once Covid hit. Chinese households also tend to save more than American households because there’s no social safety net (like Social Security and Medicare). A big part of those savings went into the real estate market (or in investment vehicles tied to real estate), but not anymore amid crashing home prices. That’s likely a reason why Chinese households have bought more gold over the past year.

Is This Time Different?

Chinese authorities have historically been against “handouts” to households. But that may be changing ever so slowly. The Chinese leadership seems to be acknowledging that stimulus needs to go further than the PBOC’s monetary easing. Details from the latest Politburo meeting, headed by President Xi Jinping, indicate a discussion of economic matters and boosting fiscal spending. This included the issuance of ultra-long government and special-purpose municipal bonds.

The City of Shanghai is piggybacking off of this already. They are planning to hand out 500 million yuan (about $71 million) in the form of consumption vouchers, including for dining, accommodation, cinema, and sports. But that amounts to about 0.0004% of GDP. They’re going to need to multiply that by a factor of 1,000 (if not more) to meaningfully move the consumption needle.

Perhaps this time will be different, with some acceptance that the economy needs more than easier borrowing and the prospect of fiscal spending coming into the picture. The Chinese government does have more than ample space to go this route — the central government will have debt of about 26% of GDP by the end of 2024 (versus over 100% for the US and over 200% for Japan). So, it’s just a matter of will, or rather, how much pain they’re willing to endure before throwing in the towel. There have been various points over the last decade when the rhetoric (or perhaps, investors’ understanding of the rhetoric) was way ahead of what actually happened on the ground. As the saying goes, fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me. In other words, we’re going to need to see actual details of fiscal spending before coming to the conclusion that this time is indeed different.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

For more content by Sonu Varghese, VP, Global Macro Strategist click here.

02437166-1001-A