Let’s Keep It Simple

Sometimes I find it helpful when I think through a problem to state the obvious. So here it goes. Stating the obvious when it comes to trade, the main reason the US has a net trade deficit with the rest of the world is because we consume more than we produce (and we’re producing just about all we can). The “net” part of “net trade deficit” is important. It’s entirely normal for two countries to have a bilateral trade surplus/ deficit, and usually the reason is actually positive and just has to do with specialization (without denying that unfair trade practices exist and can be part of the problem too). The problem of consuming more than you produce only comes with a net trade deficit.

Also keeping things simple, the benefit of a trade deficit is international investment in the country with a deficit. We sell goods in dollars. Those dollars find their way back to the US as investment (more common) or find their way into the purchasing country’s reserves (less common). Desiring a more balanced trade picture implies desiring a more balanced investment picture. This is a common outcome in economics—downside from one perspective brings upside from another. For the US, there is also the fact that the trade deficit is partly driven by vagaries of the US tax code that promote offshoring of production by US companies to boost profits – so think of the trade deficit as something that also accrues to US companies’ bottom lines, i.e. profits, and stock prices as a result.

Going a little deeper, if our net trade deficit is because we consume more than we produce, the solution is to consume less or produce more. Of course, no one would consider the first option a “solution,” so really the Trump administration is looking at the second. Make the economy more productive. So really the aim is to reorganize the US economy around President Trump’s belief system about economic efficiency. Since our focus is always on markets, the market’s judgment thus far has been that the president has badly missed the mark in doing this in an economically productive way. Keep in mind that for more sustained productivity growth, we need strong labor markets and business investment, both of which are at risk if the tariff situation continues as is. As we note often, whether a policy is broadly good or bad isn’t determined by markets, but markets usually are effective at understanding the impact of policy on the drivers of market returns.

(We’re getting more evidence of that today, as we did when the S&P 500 put in one of its best days in the last 50 years on April 9. The catalyst for both: the president backing off from a more extreme trade positions.)

Bilateral Trade Deficits Are Not an Indicator of Unfair Trade

Maybe this is beating a dead horse at this point, but I think it’s worth revisiting. Bilateral trade deficits are meaningless as a gauge of whether the trade between countries is fair. If Country A, B, and C have different specialties or production advantages and because of that, A has a deficit with B, B with C, and C with A, the net deficit can still be neutral but there are bilateral trade imbalances all around, and that’s actually a good thing!

Let’s say Country A is really good at making forks but bad at making knives; Country B is really good at making knives but bad at making spoons; and country C is good at making spoons but bad at making forks. If the global demand is for 100 sets of flatware per country. Country A might produce 200 forks, 0 knives, and 100 spoons, focusing more on what it’s good at and less on what it’s bad at. That has nothing to do with unfairness; it’s just smart trade. If instead Country A decided to make 100 of each, all three countries would be the poorer for it since Country A’s productivity (and income) would fall. As a result, demand might hypothetically fall to 90 sets of flatware (an exaggeration, but it captures the idea). Even worse, if Country A decided to put a tariff on knives to even out production, prices on flatware would rise, demand at that price fall, and everyone might end up making 75 sets of flatware, a hypothetical 25% drop in flatware GDP!

The deficit one country has with another, in most cases, has nothing at all to do with trade barriers. It basically reflects the choice of a lot of individual actors in country A and B to focus on what they’re good at because they can do it more productively. These actors are making efficient choices about how to allocate resources. Those decisions make the entire global trade system more productive, raising the standard of living across the board. That’s the way capitalism at its best is supposed to work.

The Real Goal Is Higher GDP Growth

The heart of the problem is the president wants the US to produce more and has a particular vision of what he wants us to produce (more goods, less services). Another way of saying that is that he wants to lift the level of potential GDP growth, assuming the goods we will produce instead of services have greater value-add (setting aside the question of how workers would seamlessly shift from the service sector to the goods-producing sector). That is a noble goal that every president should have. But the market-unfriendly means of doing that is the attempt to centralize power around one individual who believes himself so uniquely gifted that he should be empowered to reshape the US economy, and by extension the global economy. That approach does not have a history of success, but perhaps it’s fair to say it’s no more a reshaping of government and the economy than what FDR did. Either way, in general we know that interfering with free markets at that scale, whether it’s right-leaning nationalist anti-capitalism or left-leaning socialist anti-capitalism, tends to come at a cost.

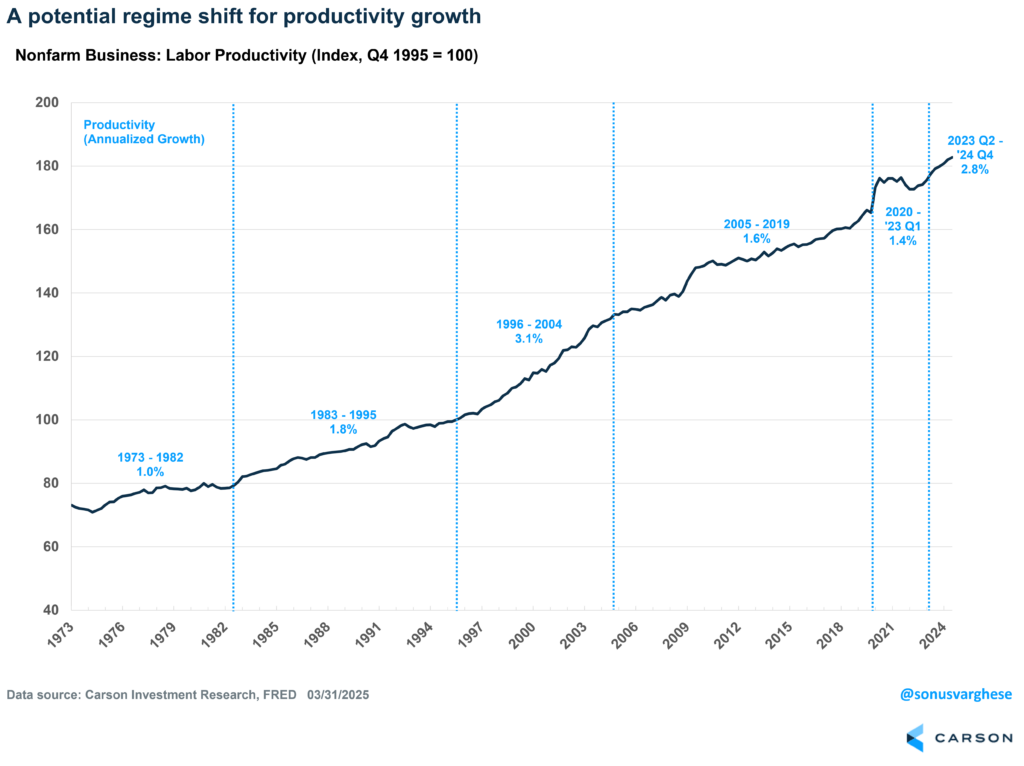

Another problem is the US economy post-Covid was already running at a relatively high and improving level of efficiency. My colleague Sonu Varghese was writing about this extensively. It was one of the reasons for our “no recession” call in 2024 and one of the reasons we saw post-election upside potential from a rise of “animal spirits” with a greater emphasis on supply side policy in 2025. Unfortunately, any goodwill associated with that policy has likely been largely squandered for now, but has not necessarily disappeared altogether.

The problem is, there is no magic wand for improving GDP growth. There are two basic ways to improve real GDP:

1) raise the aggregate hours worked, which usually means increasing the number of people working

2) raise what can be produced in an hour of work, also known as productivity

Labor force participation was already near a multi-decade high and unemployment near a multi-decade low when President Trump took office and there isn’t much scope for improvement in the near term. In fact, the risk is in the other direction with the US becoming less competitive in attracting global labor. We also believe productivity was already seeing structural improvement we hadn’t seen in decades in 2023 and 2024, a trend the Trump administration was well positioned to solidify and extend.

Instead, the focus has been almost entirely shifting course and focusing on capital intensive, potentially lower productivity manufacturing. But the US already has one of the most productive workforces in the world, and part of that is because of the choice by individual economic actors in how to most productively put resources to use. Those choices have given the US one of the most advanced, productive workforces in the world and supported a culture of innovation-driven entrepreneurship, which has helped in turn make the US a growth leader among more developed economies.

Where Did Manufacturing Go?

Where did manufacturing go? The usual way of looking at GDP doesn’t really tell the story. The most common way of measuring GDP (because it’s the easiest to calculate) is not to look at production at all but “final demand,” that is, all the things bought that aren’t just going into something else that will be sold later. This is what gives us the well-known formula GDP = C + I + G + (X – M). That is, GDP is consumer spending + private business investment spending + government spending + net exports (exports minus imports). But this is really a formula that looks at GDP from the perspective of demand rather than production. It’s two sides of the same coin, but a more convenient way to do the calculation. A small wrinkle is it has to be “final demand.” That is, if “parts” cost $5 and someone puts three parts together and sells it for $20, that $20 covers the production from the three sellers who made the parts and the additional $5 from the final seller. You can’t double count the intermediate parts.

This is easy to calculate because you don’t have to determine the separate value added at each individual stage. You just need the cost of “final demand” (the $20). When we say that consumers make up 70% of GDP, what we’re really saying is that they make up 70% of that final demand. In another sense, they actually make up 0% of GDP because they don’t “produce” anything. (At least when they’re wearing their consumer hat—most consumers also work and so contribute to production.)Another way to think about is that one person’s spending is also another person’s income. In the example above, the final seller made income of $15 (final sales price minus cost) and the 3 original sellers made $5. Total income produced would be $20, and that’s essentially how “Gross Domestic Income” is calculated.

We also have data that actually does look at the contribution of different industries. It just takes longer to calculate. In the example above, that’s the three companies that made the parts that went into the final product (value add of $5 each) as well as the one that put them together (value add of $5). That’s the same $20 altogether, but it’s broken down into the value-added pieces. We don’t get those numbers immediately, but they provide some insight on how the US economy has evolved over time. Here’s a “snapshot” of the economy using this “value added” approach based on the final year of each decade back to 1950.

We can see that manufacturing (durable and non-durable goods) has declined by 16.7 percentage points over those 70 years, from making up 26.7% of the economy to 10.0%. What has risen in its place? Services. First what I’ll broadly call financial services (“finance, insurance, real estate, rental, and leasing”). That has grown by 10.4 percentage points since 1950 and is the business the president has chosen to be in. Then professional and business services (+9.3%-points growth since 1950). Then education and health care services (+6.8%-points). In 1950, those three categories were 16.8% of the economy.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

By the way, manufacturing did not really shrink over that time. Over the last 25 years (2000-2024), manufacturing value-add grew by about $1.5 trillion, and the sector’s total value-add is currently at $2.9 trillion – which by itself would make it the 8th largest economy in the world, behind France. It’s just that as a share of GDP, the sector has shrunk over this entire period, from 15.5% in 1999 to 10% in 2024. Rather than the manufacturing sector getting smaller, the US economy grew more quickly and manufacturing did not grow at that same pace.

That’s the current mix for the “US economy” that has been the envy of the world. Granted, those changes have not been evenly beneficial across every demographic. Education has grown in importance, and it’s no surprise to see a growth in finance and professional services as a result. Undergraduate business degrees are by far the most common bachelor’s degree in America, making up 19% of all degrees in 2021-2022 according to the National Center for Education Statistics. That’s followed by health professions, at 13%. (Degrees in the liberal arts and humanities, the image many have when they think of American universities, make up under 2%.)

Good Old American Know-How

A former colleague of mine, John Canally, now an economist at TIAA, used to say that the most important export of the US is “good old American know-how.” That still holds true today. Perhaps as part of a social agenda, it’s wise to place less value on that and compel American businesses to focus more on manufacturing. But the markets have been recognizing the costs and the risks involved. Free trade has to be fair trade and it’s worth building policy around that goal. But if there’s a policy agenda in addition to that of dictating the direction of the economy from the White House, markets have spoken clearly on the economic pain that may create. Perhaps there’s a path that accomplishes an outcome that markets are missing, but odds are if this agenda continues to get pushed hard, markets are not yet done pricing the damage. On the other side of things, a much more restrained approach may bring market upside few are expecting right now.

For more content by Barry Gilbert, VP, Asset Allocation Strategist click here.

7892806.1-0425-A