The title was actually a question I put to Professor Jeremy Siegel when Chief Market Strategist Ryan Detrick and I hosted him on a live Facts vs Feelings episode recently. (You can listen to the episode here.) Of course, the question assumes you need luck while investing, and I think a lot of you reading this will likely agree that we need a little bit of luck. Or do we?

Prof. Siegel, who’s studied markets as extensively as anyone, had 4 interesting responses:

“The great thing about investing is that you don’t need luck. You stay with the market, in sensible investments, and in the long run you are going to be a winner.”

He added that people think stocks are gambling, but it’s probably the only gambling around where the odds are with you, and not the house. Plus, stocks beat inflation.

There’s actually quite a lot in just this little bit. Let’s unpack it.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

“In The Long Run You Will Be a Winner”

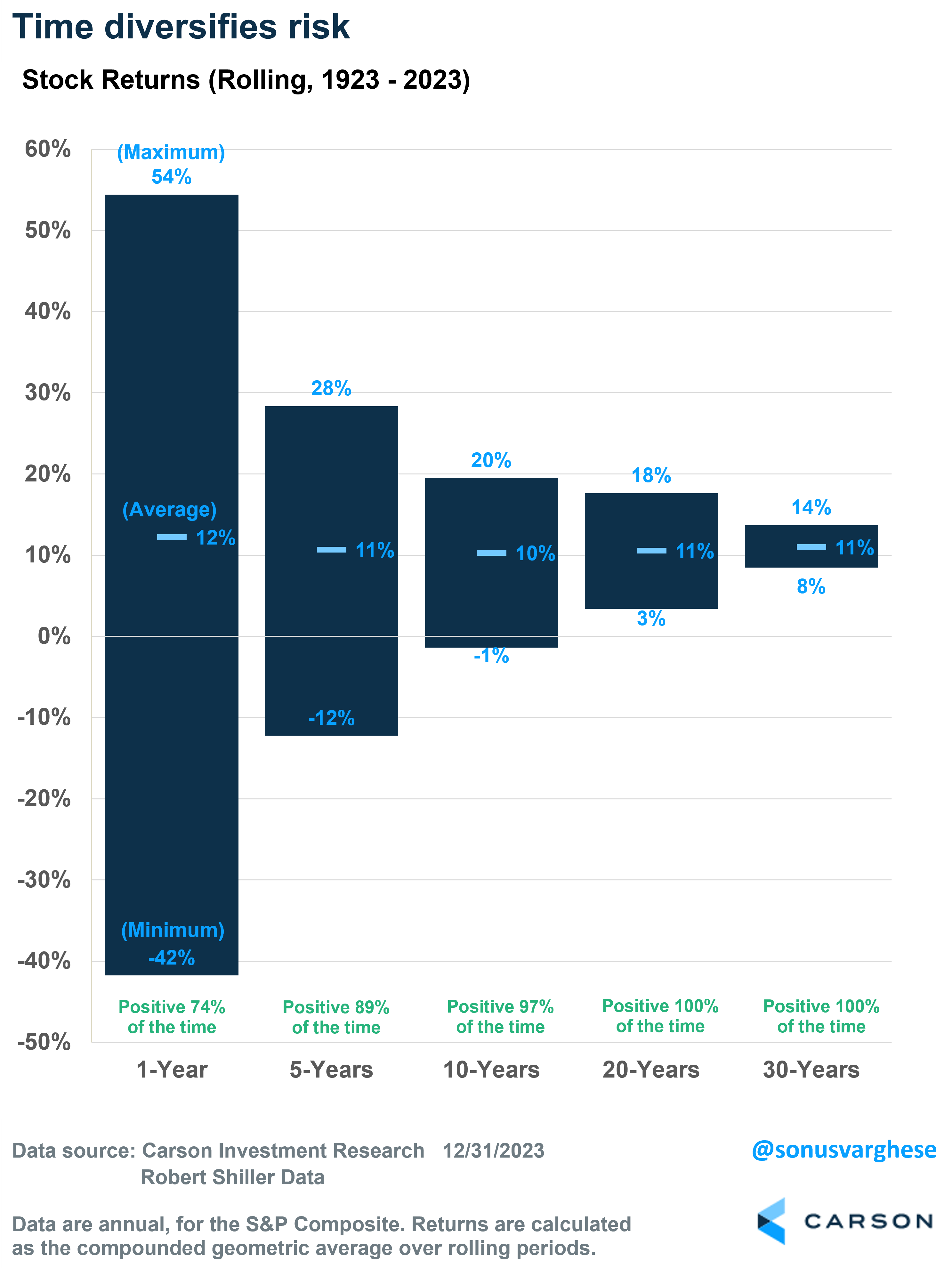

In other words, time is how you positively expose yourself to luck while investing. Stock market returns are quite random over short time periods like a day or a week. The variation can be significant even over a full year (which is the typical frequency at which a lot of investors evaluate performance). Looking at the last 101 years (1923 – 2023), stock market returns have been positive across 75 calendar years (74% of the time), but as you can see in the chart below, the variation is massive. We’ve seen calendar year returns as high as 54% (1932) and as low as -42% (1930). In fact, in 12 of those calendar years, annual returns were below -10%.

But as the time horizon extends, the odds of success go up. Returns across rolling 5-year periods were positive 89% of the time and ranged from -12% to 28% (annualized). Move to 10 years, and it’s even better, with rolling 10-year returns positive 97% of the time. There’s never been a rolling 20- or 30-year period in which stock market returns were negative. In fact, the worst 30-year return was 8.5% (1929 – 1958) – which meant $10,000 invested would have “only” turned into about $115,000.

In short, time diversifies risk.

“Stay With the Market, In Sensible Investments”

I think it’s safe to say, Prof. Siegel meant that you want your equity portfolio to be broadly diversified, perhaps in something like the S&P 500, or the total stock market, which includes mid- and small-cap stocks. The results I showed above are for the S&P 500. While it’s widely thought of as a “passive” index, the components within are anything but “buy and hold.”

- As companies get larger by market capitalization, they become a larger portion of the index. So, there’s inherent (long-term) momentum within its construction.

- The S&P 500 “index committee” actively decides which companies go in and out of the index each year, manifesting in about 5% turnover per year, i.e. about 20 names go in and out on average. Just since 2015, about 180 companies in the S&P 500 have been replaced, so the S&P 500 you bought in 2015 is very different from the S&P 500 you buy today.

In short, the broad S&P 500 index, or “the market” evolves with the economy, which is a great way to grow and preserve wealth.

In contrast, concentrated stock positions can sometimes be a great way to grow wealth (this is where luck really comes in), but it’s almost always a terrible way to preserve wealth. Hendrik Bessembinder, a Professor of Finance at Arizona State University, looked at about 26,000 stocks listed on the NYSE, Amex, and Nasdaq exchanges from 1926-2016 and found some amazing results

- Just 43% of the stocks (about 4 out of 10 stocks) have a buy and hold return above that of T-bills over their entire lifetime.

- More than half of them deliver negative lifetime returns.

- The single most frequent outcome for individual stocks over their full lifetime is a loss of 100%!

Quoting Nathan Sosner of AQR, “the fundamental statistics are rather ruthless toward single stock investors concerned with growth and preservation of their wealth”. Fortune doesn’t favor the bold in stock investing. It may seem crazy to think about it within the context of what’s happening with companies like Apple, Microsoft, and NVIDIA right now, but many investors who have very concentrated stock portfolios (or perhaps one very large holding) face one of the most consequential financial decisions of their lives:

- On the one hand, they face significant risk of catastrophic loss. Even NVIDIA has volatility about 3 times that of the S&P 500. If a stock goes down 50%, it needs to go up 100% to get back to even. Obviously, that can happen – but how often, and can you sit through it if it’s a large portion of your wealth? (NVIDIA has had a drawdown of over 50% seven times over the past 25 years.)

- On the other hand, if the stock is in a taxable account, selling it, fully or partially, can result in an immediate tax burden (of at least 15%).

Investing in concentrated stocks is not the same as investing in the broad market, like the S&P 500. Again, positively expose yourself to luck.

“Stocks Beat Inflation”

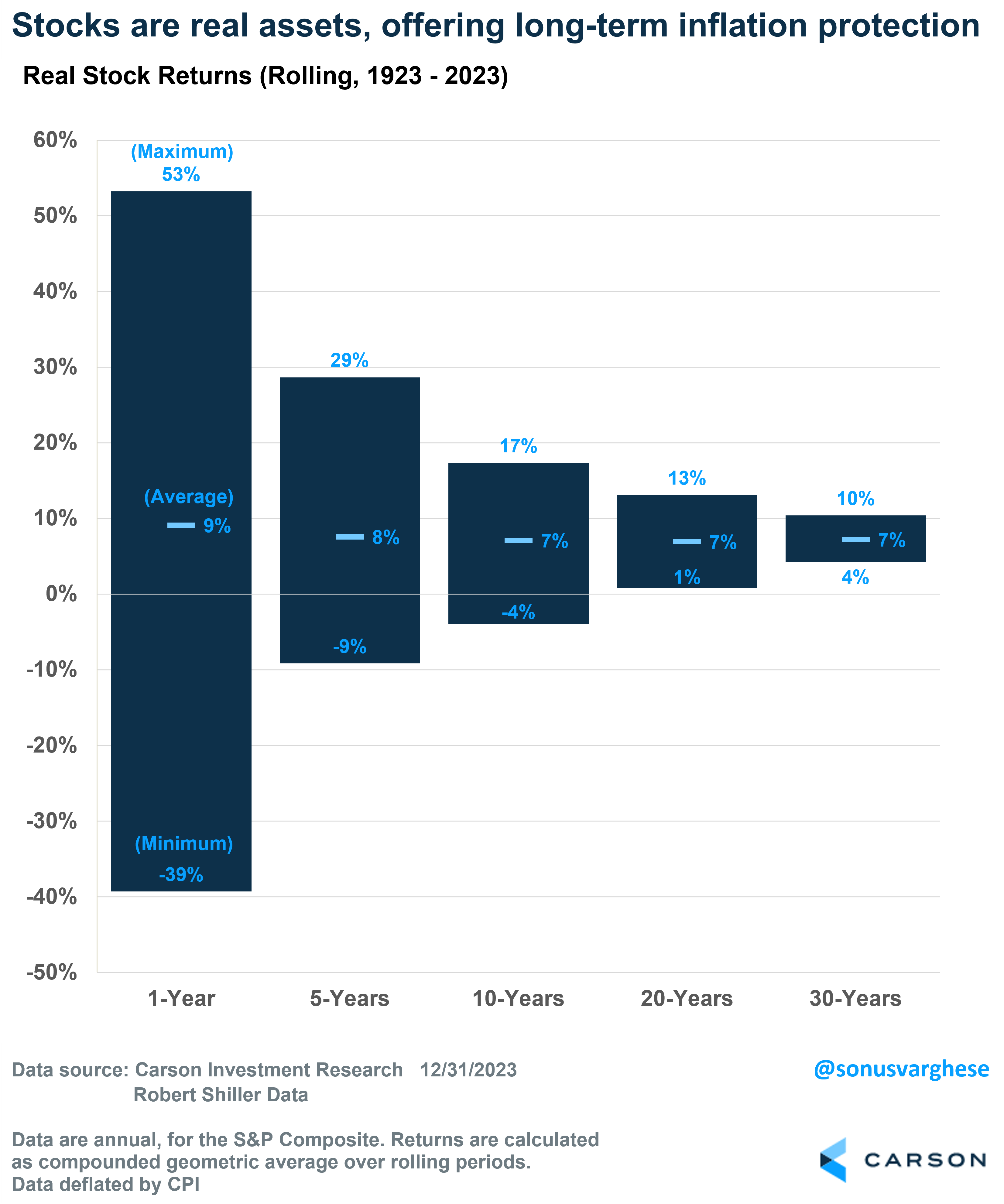

I’m glad Prof. Siegel mentioned this very important concept. I’ve written in the past about how stocks are the best “real assets,” in my opinion, as they provide long-term inflation protection (though they may not hedge inflation risk in the short-term).

I would consider stocks are “stable” assets over the long run, since time diversifies risk, but that’s true even after adjusting for inflation. Corporate earnings move higher with inflation as companies can pass rising input costs to customers. Pricing power is evident in the fact that long-term earnings and dividend growth has outpaced inflation, even during the 1970s and 1980s when inflation was high.

Here’s a version of the same chart as before, but with returns adjusted for inflation. Same story, but the average inflation-adjusted return over rolling 30-year periods (when even annual inflation of 2% matters a lot) is about 7%. And it’s never been negative so far – the worst 30-year inflation-adjusted return was 4.3% annualized, from 1956-1985 (the real return for US 10-year Treasuries was -0.5% annualized during this period).

More recently, from 1994 to 2023, the consumer price index (CPI) rose 110%, translating to average annual inflation of 2.5%. An item that cost $1 at the end of 1993 would have cost $2.10 in 2023. At the same time, stocks gained 1,662%, translating to an annualized return of 10%. In inflation-adjusted terms, the real return for stocks was 7.5%, which is very close to its average long-term real return.

That was some timeless investing lessons from Prof. Siegel, wrapped up in a few sentences. But here’s the entire Facts vs Feelings episode we did with Prof. Siegel, which I couldn’t recommend more highly.

For more content by Sonu Varghese, VP, Global Macro Strategist click here.

02288893-0624-A