Short answer: not very much. The longer answer is also pretty much the same thing, but it’s really the context around the debt downgrade, and especially the US fiscal situation, that raises important questions, not the downgrade by itself.

Last Friday evening (May 16th), Moody’s finally joined their counterparts at S&P and Fitch in downgrading US debt to one notch below their top rating, from Aaa to Aa1 (Moody’s has a 21-notch rating scale). Moody’s has actually had a “negative outlook” on the US’s Aaa rating since November 2023. They’ve now pulled the rating down a notch and moved the outlook to “stable.” Their reason for doing this was twofold: 1) increase in government debt over the past decade, and 2) higher interest payment ratios compared to similarly rated sovereigns.

Moody’s said that US federal spending has increased substantially while tax cuts have reduced government revenues. They estimate that the federal budget deficits will hit ~ 95% of GDP by 2035 (currently around 6.5%), driven by:

1) Increased payments on debt

2) entitlement spending

3) low revenue generation (tax cuts)

Does This Mean US Debt Is not “Risk-Free” Anymore?

Not at all. By itself, US debt is considered “risk-free,” and that’s not going to change. But “risk-free” does not necessarily mean a triple-A rating from the 3 ratings agencies. In fact, after S&P lowered their rating for the US back in 2011, several institutions changed their by-laws so that they can hold on to non-triple-AAA rated debt. Before 2011, several institutions required triple-A ratings from all 3 agencies, and then at least two triple-A ratings. They changed those rules to continue holding on to the what was still widely recognized as the risk-free asset, US Treasuries.

All this to say there should be no technical issue here where entities that need to hold triple-A rated debt will suddenly be forced to sell US Treasuries. That problem was “solved” over a decade ago. And if it wasn’t, rules will be changed again.

The important thing here is that US sovereign debt is issued by a country that can print money — so the US government cannot default on it, literally speaking. US Treasuries are also a not a “credit” product, and I would argue that ratings on US and other sovereigns that borrow in their own currency should not even be assigned a “credit” rating.

Speaking of, here’s a list of countries that still have AAA rated credit rating. The US economy is significantly larger than all of these (even put together) with taxation capability and ability to raise money in the bond market. (For one thing, Americans love government money markets and even longer-term treasuries in their retirement portfolios.)

Perhaps more absurd is the fact that there are two US companies (Johnson and Johnson and Microsoft) that have triple-A rated debt. These companies borrow money and the duration piece of their debt (rate sensitivity) is directly tied to US Treasuries, not to mention the fact that any calculations of their working average cost of capital is going to include a risk-free rate. That risk-free rate is US Treasuries. So it makes no sense for these companies to be rated higher than the US.

What Happened the Last Time US Debt Was Downgraded?

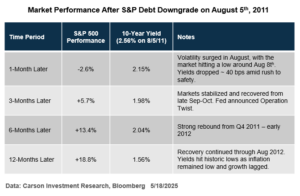

S&P downgraded US debt back in 2011 after the first big debt ceiling crisis. They put the US on “credit watch” on July 15th, and despite the US raising the debt ceiling on July 31st, S&P dropped the triple-A rating on August 5th. Here’s what happened in equity markets and 10-year Treasury yields following that debt downgrade.

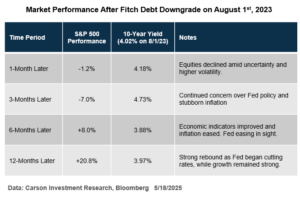

Fitch dropped its top notch rating in 2023, also soon after a debt ceiling crisis that began in June. The debt ceiling crisis was resolved by July, but Fitch moved on August 1st — saying it was driven by the huge amount of debt added during Covid by the Trump and Biden administrations.

As you can see, we saw yields behave very differently after the S&P and Fitch downgrades. Markets were volatile over the next month, but generally went to post large returns over the following year. It does get to the fact that the context around the downgrade matters, especially related to policy. So let’s take a look at the current context, which matters more than the downgrade itself.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

The Tax Bill — Prepare for a Deficit Surge

It’s not a coincidence that this downgrade came while Congress is debating a massive deficit-financed tax bill. There’s still a big question about how large the tax bill will be. It does matter in aggregate for the equity markets as well because all else equal, deficit-financed spending will boost profits — as they did in 2016 – 2019, 2020 – 2021, and even 2023 – 2024.

The tax bill is going to be large, no question. If Congress does nothing, tax rates for households will revert back to pre-2017 levels. There’s no way Republicans in Congress will allow that to happen, especially going into a midterm year. But renewing all the tax cuts will cost about $4 trillion over the next decade. In other words, that’s the cost of maintaining the status quo.

To provide an additional boost to the economy, i.e. stimulus, the bill likely has to be larger, perhaps closer to $5 trillion, with most benefits front-loaded. Also keep in mind that tariffs are effectively a tax on businesses and consumers that pulls money away from the private sector into the federal government’s coffers — so the tax bill will also have to neutralize that.

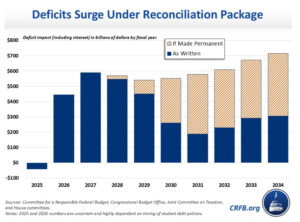

The House version of the tax bill looks like it’s going in this direction. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB) estimates that the bill will add about $600 billion (1.8% of GDP) to the deficit in 2027, the first full year when the law is in effect. In addition to maintaining current tax rates, the bill adds Trump’s campaign promises like no tax on tips and overtime, along with additional deductions for seniors. As always spending cuts are hard to come by, since nobody wants to touch Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, veterans benefits, or defense (which account for about 70% of federal spending, excluding interest payments).

Overall, the bill will add about $3 trillion in deficits over the next decade, and about $5 trillion if the tax cuts are made permanent (which is very likely — as Republicans push the next “tax cliff” off to 2028, another election year). As you can see below, the benefits (i.e. the spending) will be front-loaded while the “savings” will be backloaded. After 2027, various tax cuts will “expire” — but that’s a gimmick used to reduce the official cost of the bill, and one-time spending boosts will fade. As I noted above, that’s a boost for corporate profits in the near term.

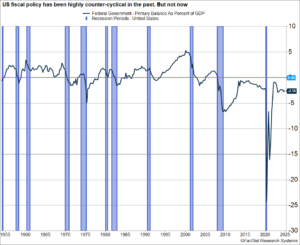

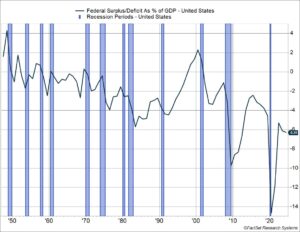

The “primary deficit” will surge by almost 1.8% of GDP by 2027, the first year in which the policies would be fully in effect. The primary deficit is the government’s budget deficit excluding interest payments. I’ll get to the full picture that includes interest payments but it’s helpful to understand what’s happening now by just looking at the primary balance (whether in surplus or deficit, since that tells you how much the Federal government intends to spend on net), and compare that to history.

The primary balance typically falls into deficit amid recessions, which shouldn’t be a surprise since two things happen during recessions:

- Tax revenue falls as incomes plunge amid rising unemployment

- Automatic stabilizers like unemployment benefits surge, in addition to direct stimulus

Historically, we’ve also seen the primary balance move into surplus as economic expansions get underway. As you can see below, the primary balance moved into surplus prior to every single recession prior to 2020. The anomaly, if you can call it that, started in 2016. The economic expansion was already running along for about seven years and the primary balance shifted even more into deficit across 2017 – 2019, mostly on the back of the 2017 tax cuts.

You can see how the primary deficit plunged to a near 25% deficit (as percent of GDP) amid Covid, but recovered to about 1% of GDP by mid-2022. But then you had the bipartisan Infrastructure Act, CHIPS, and IRA, and the primary balance shifted back into a near 2.5% deficit — well below what we’ve typically seen amid expansions. This was a big reason why we passed on calling for a recession in 2023 – 2024 and went maximum overweight equities, in contrast to a large swath of the investment industry that was predicting a recession.

The primary deficit will likely hit 4% of GDP by 2027, assuming the bill that eventually passes is close to what the House is debating, which would already be unprecedented outside recessions and wartime. That’s before interest costs, which matter too. Speaking of which, the largest beneficiary of higher interest costs is the US private sector, since they are the largest holder of US Treasuries – Americans love high yielding Treasuries, especially short-term bills (think government money market funds).

Interest costs are quite large now, running about 4% of GDP. This is why the overall federal budget deficit is currently clocking in around 6 – 6.5% of GDP. That’s larger than even during historical recessions prior to 2008!

With the tax bill, the budget deficit would be expected to rise to about 8 – 8.5% of GDP. Even during the 2008 Great Financial Crisis, the deficit hit about 9.5% of GDP. This time, such enormous deficits are in the pipeline during an economic expansion.

I’ll say this — it’s highly unlikely the US economy hits a recession if we’re going to run such enormous deficits. Plus, we’re likely to continue seeing business investment in AI (one business’s spending is another one’s revenue, and profits). So, we’re looking at a strong environment for profit growth, which may be why markets have been on a bull run recently, as Ryan discussed in his most recent blog. Of course, it’s a whole other question who benefits from this, i.e. large or small businesses, let alone which households.

It’s Not All Rosy

What I outlined is just one scenario, and there’s no certainty about what will eventually pass Congress. But if it does (and the odds are in favor of that happening given Congress and the Presidents’ priorities), we’re looking at a surge in deficit spending. But it’s also likely we see elevated interest rates for much longer, with more inflation volatility. I wrote about this in my prior blog.

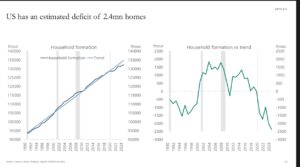

A lot of folks who worry about government deficits and debt worry about its impact on our children and grandchildren. I would argue that large fiscal deficits, and elevated interest rates, are already taking a toll right now. Case in point: housing. A large chunk of American households (generally older) continue to benefit from low interest rates through 2021. But there’s a huge cohort of 25 – 40-year olds who cannot afford to buy a home right now. Keep in mind that wage growth has eased a lot from 2022, from over 6% per year to about 3%, even as mortgage rates remain near 7%. A big driver of economic growth is household formation, and as this chart from Torsten Slok (Chief Economist at Apollo) illustrates, that’s running well below trend right now. And this is likely to continue as long as interest rates remain elevated.

The long and short of this is that we can have one of the following:

- Huge government deficits that prevent a near-term recession and provide a boost to profits, and the stock market. But it comes along with higher rates that hurt cyclical areas of the economy like housing (and even manufacturing)

- Tighter fiscal policy (and an easing of monetary policy) that leads to lower interest rates and boosts housing and other interest-sensitive areas of the economy, leading to an acceleration of economic growth

Ultimately, it’s all a policy choice. All eyes are on DC for the moment. In the meantime, take a listen to our latest Facts vs Feelings podcast, where we were joined by Skanda Amarnath, the Head of Employ America. Skanda and his team have been spot on with respect to identifying the dynamics of the economy over the last few years, and so it was great to chat with him. We covered pretty much everything, including monetary and fiscal policy — so don’t miss this one.

For more content by Sonu Varghese, VP, Global Macro Strategist click here

7991954.1. – 5.21.25A