The August payroll report was expected to be soft, and it was worse. The bottom line is that the labor market is in trouble, but that cements expectations for a rate cut in September.

The economy created just 22,000 jobs in August but take that with heaps of salt – the number is going to be revised significantly (though its hard to predict in what direction). Slightly more reliable numbers are the revised estimates for June and July and the news wasn’t good:

- July payrolls were revised up by 6,000: from +73,000 to +79,000

- June payrolls were revised down by 27,000: from +14,000 to -13,000

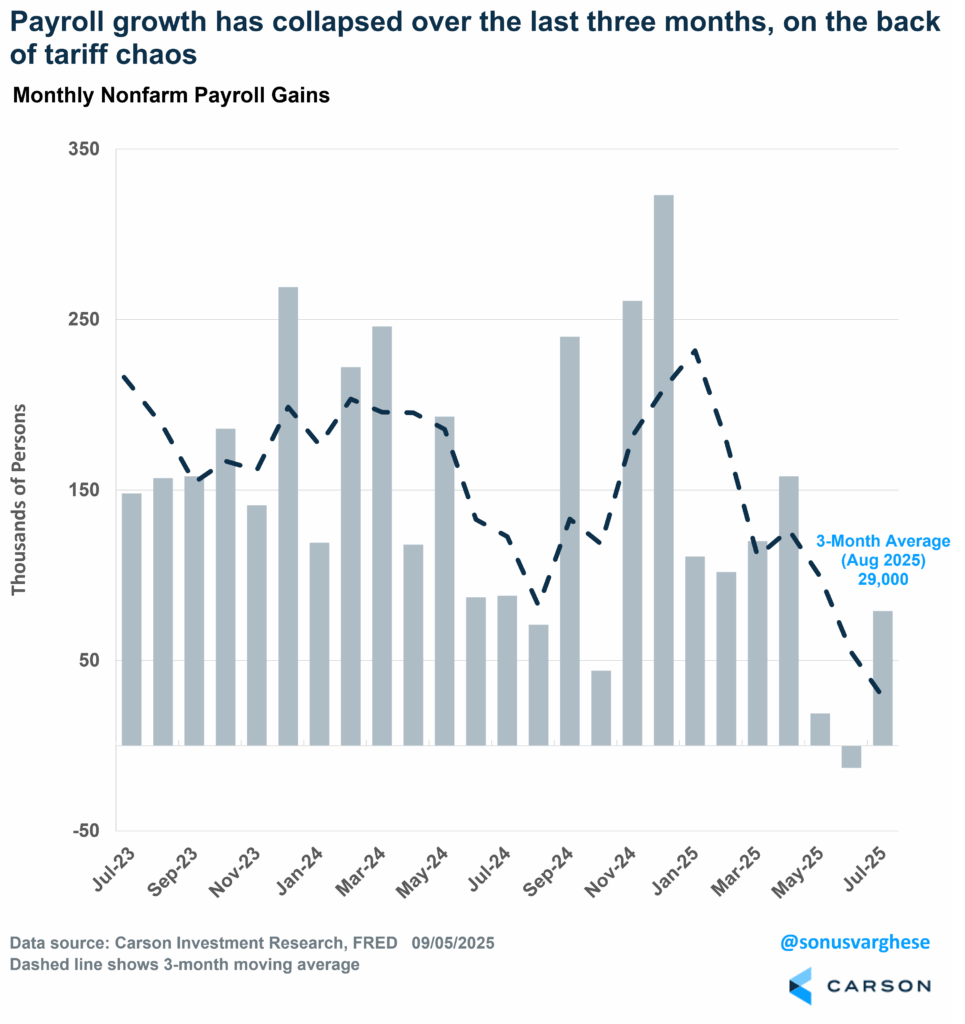

Anytime you get a month with negative payroll growth, that should be a big flashing red signal. Historically, that only happens near recessions. But even if you take the 3-month average, that’s only 29,000. For perspective, the 3-month average was 111,000 in March and 209,000 back in December 2024. We’ve seen a really sharp slowdown over the last few months, and it shouldn’t be a huge surprise given the tariff chaos in April and May.

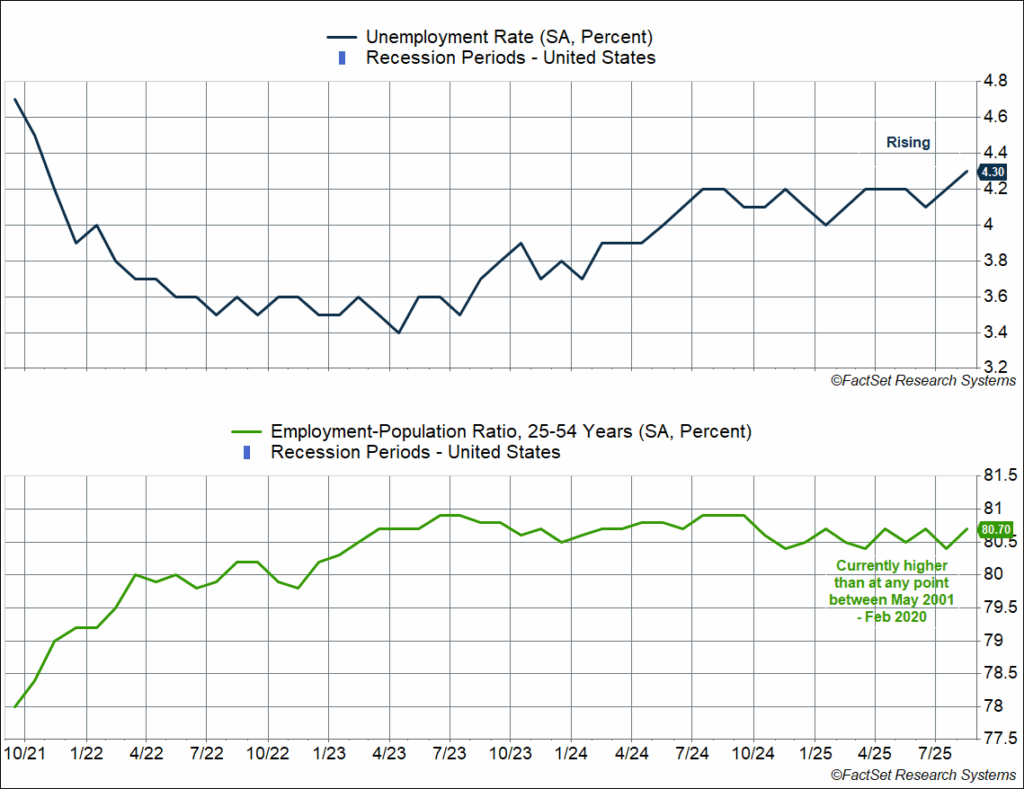

Now, the economy likely doesn’t need to create as many jobs as it did last year to keep up with population growth, since immigration has stalled. But there’s no question that hiring is really weak, which is pushing the unemployment rate higher. The unemployment rate hit 4.32% in August – that’s historically low but it’s moving in the wrong direction and just hit the highest level since October 2021. The only plus in the payroll report is that the prime age employment-population ratio (which sort of controls for an aging population and labor force definitions) picked up to 80.7%. That’s higher than at any point in the 2000s and 2010s expansion cycles. The fact that this is stable tells you that labor market weakness may be concentrated amongst young and older people – and usually the younger set starts to see trouble before everyone else.

Even Worse Under The Hood

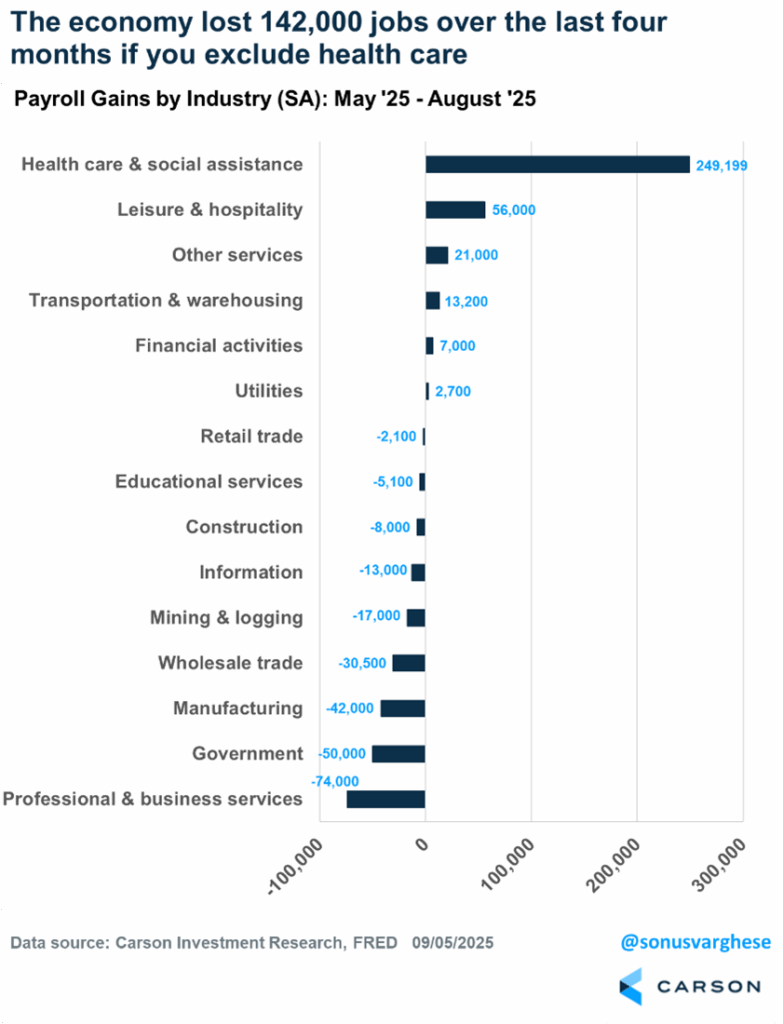

From May through August, the economy created 107,000 jobs (the post-Liberation Day phase). But get this: the health care sector created 249,000 jobs. Without that, the economy would have lost 142,000 jobs over the last four months. The weakness is across the board in cyclical areas:

- Professional and business services lost 74,000 jobs

- Manufacturing lost 42,000 jobs

- Wholesale trade lost 31,000 jobs

- Construction, which had been bit of a bright spot a few months ago, lost 8,000 jobs

The government sector also lost 50,000 jobs over this period but there’s no way to sugar coat the fact that there’s real weakness in the private sector. The tariffs have clearly taken a toll, which is why cyclical areas are struggling. There was softness even prior to May – manufacturing had lost 84,000 jobs over the twelve months through April 2025 – likely due to elevated interest rates. But we’ve seen a collapse in recent months.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

What Next? Expect Rate Cuts

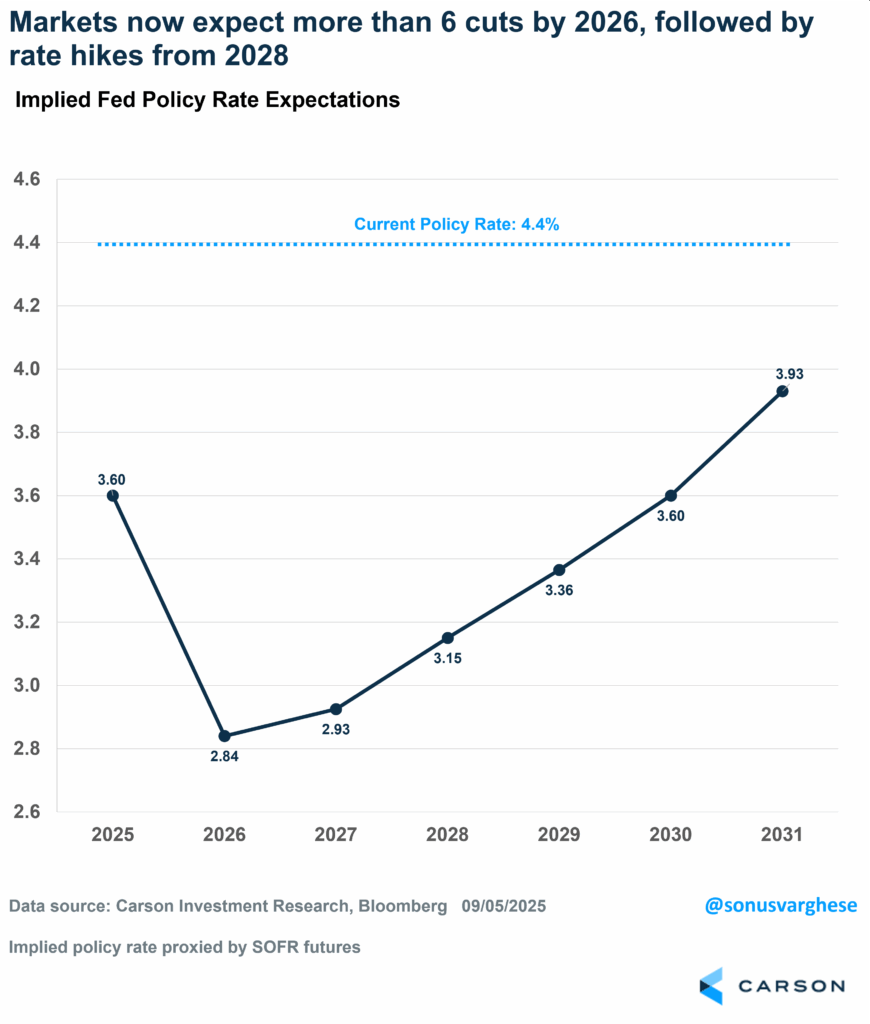

The weak jobs report cements a rate cut in September and even raises the odds of a larger 0.50%-point cut (though this seems unlikely). In some ways, the situation over the summer mimics what we saw a year ago, when labor market weakness led to a big 0.50%-point cut by the Federal Reserve (Fed) at their September 2024 meeting, followed by two more 0.25%-point cuts in November and December of last year. But there are two crucial differences:

- The policy rate was way more restrictive a year ago, at 5.4% versus 4.4% today

- Inflation was coming down whereas it’s heading in the wrong direction now (and remains well above the Fed’s target)

I’ve written a lot about inflation recently, and Ryan and I discussed it on our most recent Facts vs Feelings episode as well. So, I won’t belabor the point beyond saying that the Fed has an inflation problem. It would be one thing if all the heat was coming from durable goods, since you could argue that’s “transitory”. But there’s heat in services as well and it’s harder to brush that off as tariff-related. Note that the Head of the President’s Council of Economic Advisors (and the President’s nominee to take the vacant seat on the Fed board of governors), Stephen Miran, has argued that tariff’s are not the cause for inflation heat – in which case the Fed would have an even bigger problem as it would be harder to brush it off as transitory and “one-off”.

What’s interesting is that investors are not only pricing a rate cut in September – markets are pricing in 3 cuts in 2025 (for a total of 0.75%-points), and several more in 2026, taking the Fed policy rate from 4.4% to 2.8% by the end of 2026. This is way beyond what would be priced in if you just expected an “insurance” cut from the Fed (to protect the labor market). It looks like markets expect President Trump to get his people on to the Fed by next year, and they push through rate cuts like he wants. And as I noted above, this is in the face of inflation remaining above the Fed’s target and moving in the wrong direction.

Is Bad News Good News?

There’s a temptation to treat upcoming rate cuts as “good news” – after all, lower rates should give a boost to cyclical areas, notably housing. But I’m always wary of taking bad news as good news. If the labor market is weak, aggregate income growth (across all workers in the economy) will be weak. Less income means less spending. And that will hurt profits. So bad news in the real economy, if it continues, will be bad news for the market as well.

Right now, aggregate income growth is shockingly weak – running at an annual pace of just 2.4% over the last three months. It’s being driven by the big pullback in payroll growth, soft wage growth, and softer hours worked.

I’d be cautious about treating bad news as good news. Bad news is bad news, especially when it comes to rate cuts that are being driven by labor market weakness. Yes, consumers can take on debt to fund consumption if rates are lower, but not if they’re worried about their job (or if they don’t have one). Contrast this with rate cuts that come about amidst a strong labor market and productivity growth – which would drive inflation lower. That would be really good news (similar to the mid 1990s), but it’s not what we have now.

The open question right now is whether lower interest rates can stave off the slowdown in labor markets, or whether it’s too late. Other signals, whether its economic data (like spending) or market-related data (like credit spreads), don’t point to recession, or even close to one. There’s also all the AI-related spending that’s holding up GDP growth. Normally, this sort of investment growth would boost employment but AI-related investments don’t do that, at least not to the extent we saw in previous investment-led booms (like in the 1990s). Also, if rate cuts end up boosting cyclical activity, we could also have a bigger inflation problem on our hands, since inflation is already elevated.

All this to say, this is a very different environment from what we’ve faced at any time over the last few decades, and so we’ll be paying close attention to the data and writing about it. Ryan and I will continue discussing it week after week on our Facts vs Feelings podcast as well. Take a listen below.

8362329.1.-05Sept2025A

For more content by Sonu Varghese, VP, Global Macro Strategist click here