In our 2025 Outlook, we highlighted the threat of tariffs and risk of elevated interest rates if the Federal Reserve doesn’t cut. Well, both have manifested now.

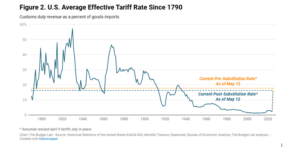

Average tariff rates, even after the China pause, are at the highest level since 1934 — rising from 2.4% at the start of the year to 17.8%. If you assume imports will fall as Americans switch to locally produced goods, the average tariff rate would be at 16.4%, the highest since 1937. The good news is that we have tariffs, and now there’s less uncertainty about it. Markets can price in what we know, not what we don’t know.

One big impact of the tariff uncertainty is that interest rate cuts have been taken off the table until at least September. Market-based probability of at least one rate cut by July is currently less than 40%. So the risk of elevated rates remains in place, and as I wrote in a previous blog, the status quo is not benign — policy is actually getting tighter since wage growth is easing.

What hasn’t manifested yet are the opportunities we talked about in our 2025 Outlook, and the main one there was tax cuts (in addition to deregulation). Let’s talk about that.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

How Big Will the Tax Bill Be?

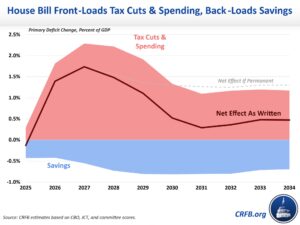

When I say how big will the tax bill be, I’m really talking about deficits. All else equal, deficit-financed spending will boost profits (as they did in 206-2019, 2020-2021, and even 2023-2024). If Congress does nothing, tax rates for households could revert back to pre-2017 levels. Simply put, there’s no way Republicans in Congress will allow that to happen, especially going into a midterm year. But renewing all the tax cuts will cost about $4 trillion over the next decade. In other words, that’s the cost of maintaining the status quo. To provide an additional boost to the economy, i.e. stimulus, the bill likely has to be larger, perhaps closer to $5 trillion, with most benefits front-loaded. Also keep in mind that tariffs are effectively a tax on businesses and consumers that pulls money away from the private sector into the federal government’s coffers — so the tax bill will also have to neutralize that.

The House version of the tax bill looks like it’s going in this direction. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB) estimates that the deficit will surge by almost 1.8% of GDP by 2027 (about $600 billion), the first year in which the policies would be fully in effect. As I noted above, that’s a boost for corporate profits in the near term.

Of course, there’s still a long way to go. The Senate will likely overhaul the House bill in a big way, and likely in a fashion that leads to even larger deficits. In any case, this will be a big deal and is something we’re keeping a close eye on.

How Will the Bond Market Take Higher Deficit Spending?

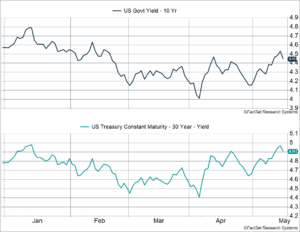

Interest rates have been rising recently, even after a soft inflation report. 10-year yields rose above 4.5% before pulling back to 4.45%. 30-year yields surged to 4.97%, inching close to the pea level of 5.11% we saw back in October 2023 (which was the highest since 2007). 30-year yields surging in this manner should tell you that this is not a story about higher growth expectations. Long-term growth expectations haven’t really changed much (likely around 2 – 2.5%), and so this surge is being driven by something else.

It isn’t because of higher inflation expectations. One-year ahead inflation expectations, as measured by inflation swaps, are running around 3.2% — not a surprise given the expected hit from tariffs. But long-term inflation expectations, as measured by the difference between nominal and real Treasury yields are consistent with the Fed’s target of 2% inflation.

The fact that long-term inflation expectations remain “anchored” to the Fed’s target tells you is that the market still buys the Fed’s credibility vis-a-vis keeping inflation close to their target of 2%. Of course, they may need to keep rates higher for that. After all, to a first approximation, long-term rates are average expected short-term rates over the next several years. But there’s another factor beyond this as well, the “term premium.”

The term premium is the additional return longer-term investors demand for future uncertainty, including inflation uncertainty. If there is more inflation uncertainty, they’ll demand more or a “term premium” when buying a long-term bond instead of a series of short-term bonds.

One thing to keep in mind here is that the Fed’s inflation mandate is to keep inflation “low and stable”. Usually the focus is on the first word (“low”), but “stable” is critical as well. Inflation may very well average 2% over the next decade, but that does not mean it cannot be volatile. It could be very volatile, in which case investors would charge a much higher term premium.

The term premium is hard to calculate and has to be modeled, which is what several researchers including some at the Fed have done. One model from the New York Fed shows that 10-year term premiums are now at 0.74%, which is the highest level in over a decade. It’s back to the typical range we saw in the mid-2000s.

As you can see above, we saw the term premium dive after 2014, eventually hitting negative territory in 2016-2020. Negative term premia don’t really make sense if you think about it for a moment. Why would anyone charge a negative premium for holding a long-term bond instead of a series of short-term ones? Here are a couple of reasons:

- Inflation was low, and crucially, there was very little inflation volatility.

- We had huge demand for Treasuries, well beyond supply (which would drive the term premium lower), including as a portfolio diversifier since the stock-bond correlation was negative.

The term premium surged after 2020, and went back into positive territory in early 2021, driven by a much larger supply of Treasuries (amid massive fiscal stimulus). However, it fell back below zero in the second half of 2021, and remained there even in 2022, when we experienced the highest inflation in 40+ years. It was only in late 2023 that the term premium started to move above the zero level once again, and in recent months (and weeks), it’s moved even higher.

When the term premium moves higher, it could be because of one or both of two reasons (broadly speaking):

- More inflation volatility

- Excess supply of Treasuries (beyond what demand can/wants to meet)

Arguably, we have both now. Despite the pullback in extreme tariffs, the toothpaste is now out of the tube, and there’s no guarantee that tariffs won’t rise even further from here. Even if we get a trade deal (or deals), there’s no certainty that President Trump will maintain that. His own trade deals from the first term, including USMCA (NAFTA replacement) and trade agreements with Japan and South Korea, were left to the wayside with round two of tariffs. Even beyond the next three years, there’s enormous uncertainty as to what future administrations will do with the tariffs, and any existing trade deals (which may not even have been fully negotiated by then). All this is a recipe for more inflation volatility, and why shouldn’t investors demand a higher premium from long-term Treasuries if that’s what we have?

The other factor is the tax bill being debated in Congress right now, which as I noted above could increase the deficit by $4-$5 trillion, including higher interest on the debt. That means there’s going to be a lot more supply of US Treasuries coming onto the market, and so even a marginal decrease in demand for Treasuries could result in much higher “net supply”, driving term premiums (and yields) higher.

You may be thinking that it’ll be foreigners who have reduced appetite for Treasuries. Perhaps, but even the US private sector may not want Treasuries to the same degree they did back in the 2010s. If inflation volatility is expected to be high, the stock-bond negative correlation would break down, and there would be less “hedging” utility for long-term Treasuries.

None of this is to say that yields will jump higher if we get a massive deficit-financed tax bill. But even if interest rates stay where they are now, that may take a toll on the economy, especially cyclical areas like housing.

Equity markets have been on a nice run recently, perhaps in anticipation of a big, beautiful tax bill (which would boost profits). But from the perspective of portfolio construction, the above two questions (and their answers) matter a lot with respect to what can potentially provide diversification.

7979139.1. – 5.16.25 – A

For more content by Sonu Varghese, VP, Global Macro Strategist click here