The Federal Reserve (Fed) didn’t move policy rates at their May meeting, keeping them in the 4.25-4.50% range. This was widely expected, but all eyes (and ears) were on how they would telegraph future moves. Short answer: they didn’t. The only major change in the official post-meeting statement was that risks of higher unemployment and higher inflation have risen, but that raised a very obvious question.

If unemployment rises and inflation also rises, which side of their mandate would they prioritize, maximum employment or low and stable inflation?

Fed Chair Jerome Powell punted on the answer in several ways, mostly falling back on the refrain that they’re unable to see which way things will play out. He admitted that prioritizing one side of their mandate over the other will be a difficult judgement, but the good news is that they don’t have to decide now since the labor market looks healthy — so they can afford to wait and watch, without being in a hurry. Uncertainty has certainly increased, along with downside risks, but there’s nothing in the data yet. They still rate the economy as healthy, albeit with downbeat sentiment amongst consumers and businesses.

Focus Likely To Be on Taming Inflation, at the Expense of Employment

If push comes to shove it looks like they’ll prioritize inflation. For one thing, Powell once again noted that “without price stability you cannot achieve long periods of labor market stability.”

As I noted in a blog about Fed policy last month, it effectively means that if they’re forced to choose between taming inflation versus avoiding higher unemployment, they’re going to do what it takes to tame inflation first.

Moreover, Powell added that policy is currently in a good place, which gives them a lot of flexibility to act down the road depending on how the data comes in. But by his own admission, policy right now is “sufficiently restrictive” despite the fact that the labor market is not a source of inflationary pressure.

Keep in mind that pausing on rate cuts is not a benign status quo — policy is implicitly getting tighter because wage growth is easing. Historically, the fed funds rate rising well above the pace of wages, i.e. increasingly tight monetary policy, has constricted the economy and ultimately these situations ended up in recessions.

In short, policy is tight right now and it’s going to remain tight until the Fed sees more data.

Powell also mentioned that eventually they may decide between their two mandates by focusing on the one that is further away from their goal. So, let’s play this out.

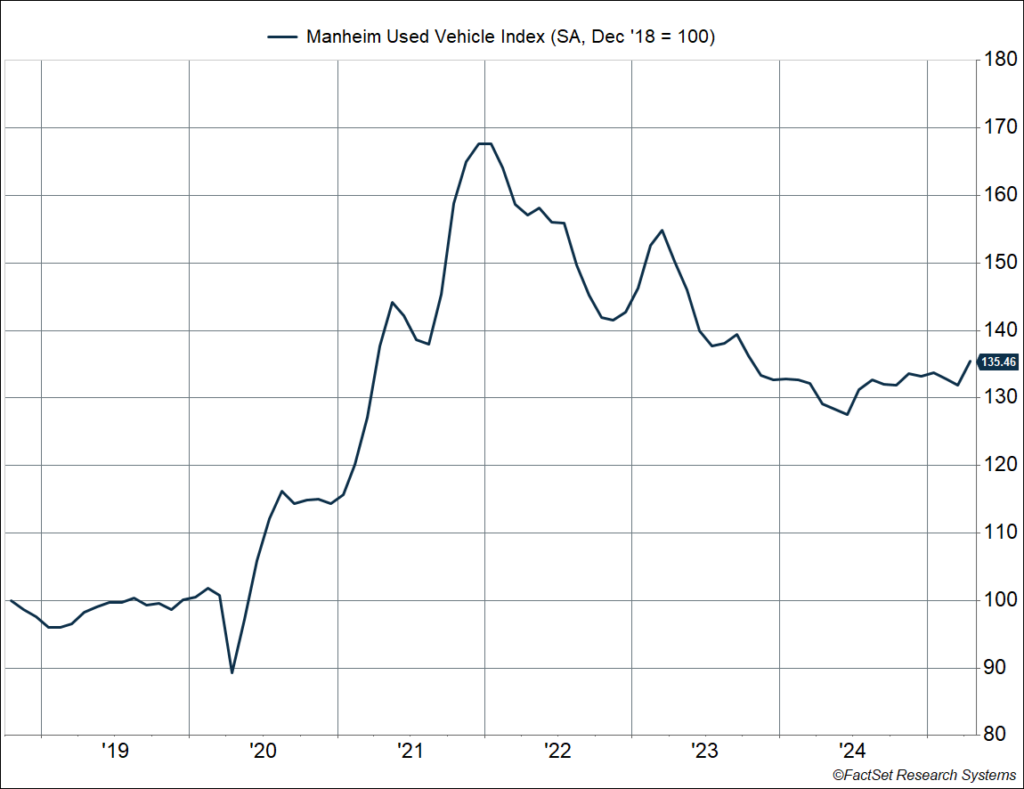

Core inflation, as measured by their preferred personal consumption expenditures metric (PCE), is currently at 2.7% year over year (as of March). That is already elevated relative to the Fed’s target of 2%. But tariff front-running and higher import costs are likely to at least partially feed into consumer prices. In fact, the Manheim Used Vehicle Index, which tracks auction prices for used vehicles, rose 2.7% in April, a significant jump compared to recent readings in the range of 0.2%. It took prices to the highest level since October 2023 and came about as Americans rushed to buy cars to get ahead of tariffs (which pushed inventories down). This is going to show up in official inflation data, albeit with a lag. We’re likely to see a sharp pickup in goods inflation over the next several months, including vehicles, appliances, apparel, and consumer electronics, pushing core PCE up to 3.5-4% by year end. Even if it may be temporary (or “transitory”), that’s a whole 1.5-2%-points above the Fed’s goal.

Now consider the employment side. Powell noted that the labor market is at or close to full employment right now, with the unemployment rate of 4.2% near a historical low. The Fed’s base case (going by their March projections) is for the employment rate to hit 4.4% by year end. Unless the unemployment rate suddenly surges to 4.8-5%, it’s hard to see the Fed prioritizing the employment side of their mandate, especially if core inflation is running near 4%.

The long and short of this: expect the Fed to stay on pause for longer. And if they do cut, that’s not going to be good news, because it’ll mean the labor market has broken (and the Fed’s only going to be stepping in too late).

The Fed’s Also Optimistic About the Tariff Situation

In a recent blog, I discussed the bull case versus the bear case for the economy and markets. My colleague, Barry Gilbert, VP, Asset Allocation Strategist, also looked at how interest rates may behave under these scenario in a blog this week. The bull case is simple: tariffs come down significantly from extreme levels, perhaps down to 10% additional tariffs on most goods, and slightly higher on Chinese imports. The bear case is what we have right now. Neither is really our base case — as Barry wrote, when uncertainty is high there really is no base case.

However, it looks like the Fed is optimistic and buying into the bull case. Powell said that since Liberation Day tariffs, the administration has entered negotiations, and so the picture could change materially — and since negotiations would likely lead to less extreme tariff levels, this is quite optimistic. That bolsters their case for standing pat and not acting pre-emptively to rescue the economy (and hard data, including recent payroll data suggest nothing’s broken yet).

Of course, that also means rates stay elevated, and “sufficiently restrictive” for longer. It likely means the Fed will not cut interest rates at their next meeting in June, and perhaps not even in July in my view. Investors also shifted pricing for near-term rate cuts quite significantly

- The probability of a cut in June fell from about 34% on Wednesday morning to 20% after the Fed meeting was done and dusted.

- The probability of at least one cut by July moved down from 100% to 84%.

The market is still pricing in at least 3 cuts in 2025 and another 2 in the first half of 2025. That would be a relatively quick pace of cuts, i.e. about 1.5%-points over 8 meetings. In other words, markets are expecting policy to stay tight in the near term, but a slowdown later in the year (and into 2026) may push the Fed to cut more rapidly. There’s a reason why longer-term bond yields fell after the Fed meeting, despite near-term rate cut expectations fading.

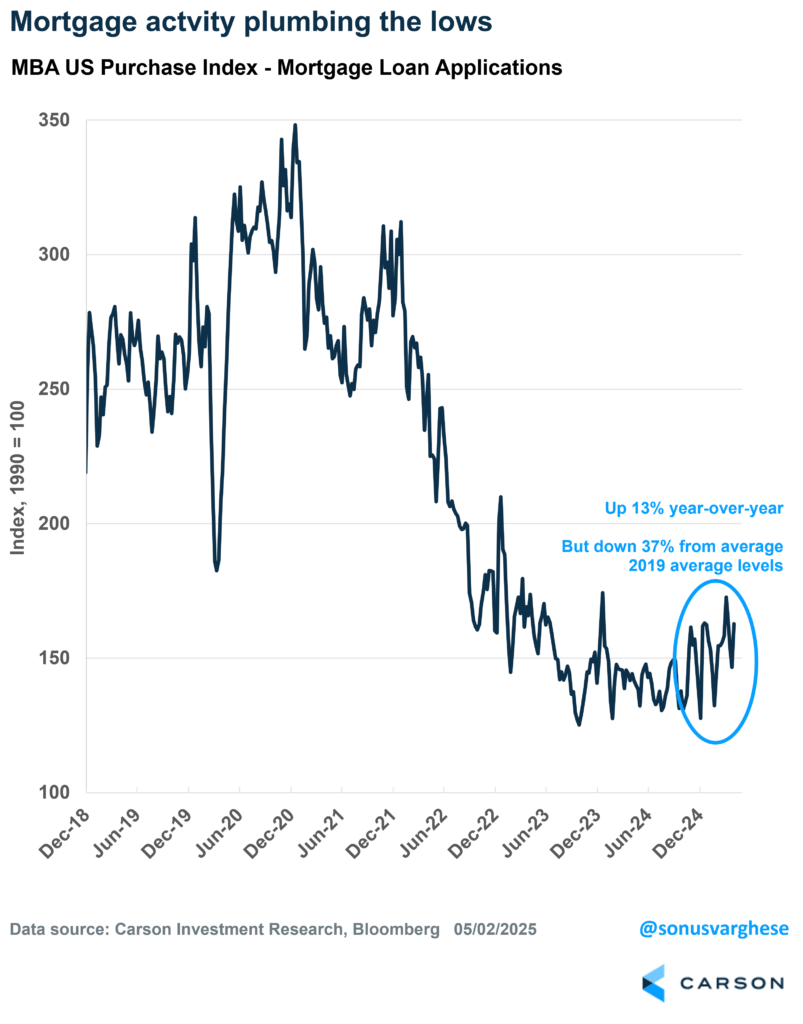

As we’ve repeatedly noted in blogs, and even in our 2025 Outlook, elevated rates are a key risk to the economy. Cyclical areas of the economy like manufacturing (which will also be hit by higher input costs) and housing will continue to struggle. Mortgage applications have picked up in recent weeks and are currently running 13% above where they were a year ago, but they’re still a whopping 37% below average 2019 levels. Refinancings are down 59% from average 2019 levels. Remember, this a key mechanism by which homeowners can access home equity (which they have more of), but the door is shut because of elevated rates.

The whole tariff situation, and ensuing uncertainty, simply increases the risk of tight monetary policy, and elevated interest rates becoming a larger and larger drag on the economy.

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

For more content by Sonu Varghese, VP, Global Macro Strategist click here.

7947146.1-0525-A