“We are navigating by the stars under cloudy skies.” -Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell

- The Fed is likely underestimating the neutral level of the fed funds rate, which it had at 2.6% in its last summary of economic projections, and will probably need to revise it higher.

- We believe the Fed’s neutral rate is too low primarily because of overly subdued growth expectations.

- Some structural changes in inflation and the tendency of the Fed to shoot a little low are also contributing to a low expected neutral rate.

- As a result, we believe we are in a “higher for longer” rate regime. We expect rates to fall, but the neutral rate will be well above what we saw last cycle.

- Despite this, we are comfortable with the return potential of intermediate bonds over short-term bonds.

- At the same time, we believe the role of bonds as diversifiers is diminished in a higher-rate environment and investors will need to look to bond alternatives for added diversification.

As we start to look toward the second half of the year for fixed income, one unheralded theme is changing expectations about the “neutral” fed funds rate, the rate that would be low enough to support full employment but high enough that it would still promote low and stable inflation near the Fed’s target of 2%.

The neutral rate exists by definition, but it’s not directly known. It can only be modeled or estimated and can change with structural changes in the economy. Keep in mind that much of the time, the Fed is not “neutral”— policy is either restrictive or accommodative. But the neutral rate is a kind of center of gravity. All else equal that’s where restrictive or accommodative rates will be pulled.

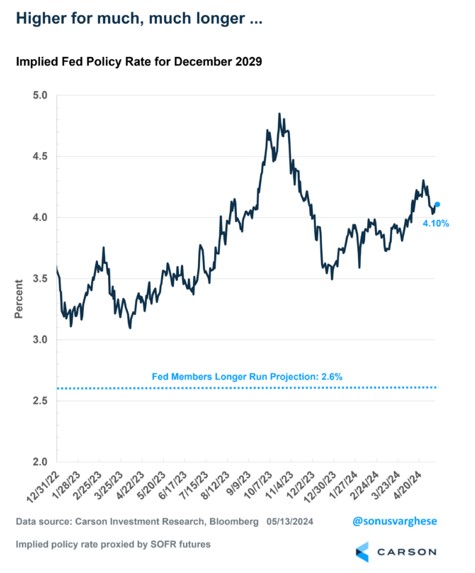

A key piece of rising rates this year has been a shift in the market’s estimate of the long-run fed funds rate. As seen below, using market-implied expectations of the fed funds rate five years from now as a reasonable proxy for the long-run expectation, the market view has changed from a neutral rate (including inflation) of about 3.5% toward the end of last year to 4.1%. Given a fairly stable market-implied view of inflation (based on the five-year forward expected inflation rate five years from now), the market has been implicitly projecting higher growth expectations. Market-implied views are volatile, but they can give us a sense of how the market is implicitly viewing key economic variables in real time. Notably, even at 3.5% the market was well above the Fed’s current view of the neutral rate of 2.6%.

The limitations of modeling the neutral rate and the need to be pragmatic about its level has been a major theme during Jerome Powell’s tenure as Fed chair. He has often used the metaphor of steering by stars under cloudy skies, the “stars” referring to the asterisk put after the letter for some macroeconomic variables, including r*, the estimated neutral rate. There are several models for estimating the neutral rate, and the estimates will vary quite a lot, which is why a good dose of pragmatism is needed in practice.

In contrast to market views about the neutral rate, which can be quite volatile, the views of the Federal Reserve tend to be sticky for policy reasons but also because of a strongly anchored prior assumptions that only shift slowly in the face of new evidence. From a policy perspective, the Fed’s views are a communication tool and the perception of a flakey Fed that changed its forecasts as actively as market participants would have the potential to breed chaos.

We won’t claim to know the precise level where the neutral rate should be and market views are so volatile that it’s not the place we would look to take our bearings. But in this case, we think the change in the market view is meaningful and the Fed has been slow to adjust. The main upshot is we believe rates will be higher for much longer, our basic theme for interest rates over the second half of 2024 and into 2025. We don’t expect rates will necessarily press higher. To the contrary they need to decline to get to neutral. But the neutral rate, the center of gravity, will be higher than it has been in a while.

The Fed’s Anchored to a Pessimistic Outlook

We get a picture of the Fed’s view of where rates should be over the longer run from the summary of economic projections (SEP) that the Fed shares every other Fed meeting, also known as “the Dot Plot.” All members of the FOMC, voting and non-voting, share their view of the economic outlook, with the median of those views taken to be the consensus, although it’s important to keep in mind that there are a wide range of views.

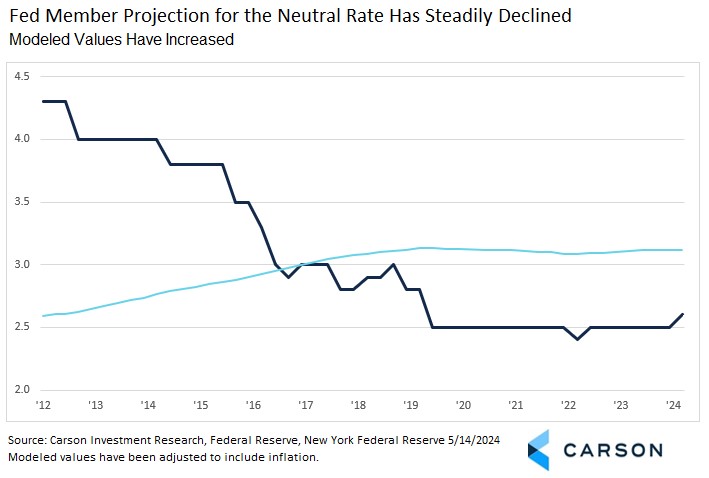

As seen below, the Fed’s median estimates of the fed funds rate over the longer run has generally steadily declined from 4.25% to 2.25% since it first started sharing the SEP in 2012. Meanwhile, the median estimate of long run inflation (PCE) has never really strayed from the Fed’s target of 2.0%, which is just the Fed’s way of saying it is capable of meeting its 2% inflation target in the long run. I’m sure if they decide the inflation target is 2.25% one day, their long-run projection will also change to 2.25%. That leaves us with a “real” longer run rate (taking out inflation) that has steadily moved from 2.25% to 0.6%. By contrast, modeled views of the neutral rate (adjusted to put them in nominal terms) have generally moved higher.

How did the Fed’s neutral rate fall so much? The Fed was responding to an extended period of low productivity and slowing labor force growth where inflation was muted. Some central banks, such as the Bank of Japan, were having deep chronic problems even raising inflation to meet its target. In the face of those challenges, the Fed shifted its policy framework to help justify low rates. Most notably, in August 2020 the Fed announced a policy of “flexible average inflation targeting” to allow inflation to run a little hot when it had run a little cool for an extended period. Yes, the timing for implementing that policy is one of life’s not so surprising ironies.

But there’s also a pragmatic element to the Fed’s adjustment. Back in 2019, an upper bound on the fed funds rate of just 2.50% was enough to start breaking the economy. Former President Donald Trump called out the economy’s vulnerability to higher rates and pressed the Fed to lower them. He was right and given inflation was low the Fed had the scope to make the move. The Fed actually achieved a pragmatic, successful mid-cycle adjustment to rates, which was soon lost to the economic consequences of the pandemic. At the time from a practical perspective an upper bound of 1.75% seemed the right point-in-time neutral rate for the state of the economy, making a 2.5% longer-run expected neutral rate entirely reasonable.

Move forward to 2023 and 2024 and an upper bound on the fed funds rate of 5.50%, over double the rate that was breaking the economy in 2019, has not been enough to undo a robust economic recovery. (Could you imagine what a 5.50% rate would have done in 2019?) But even if it had undone the economy, the need to control inflation dictated the rate. By Trump-era standards, even the neutral rate of 2.5% was viewed as a risk and you can see the further adjustment to neutral rate expectations in the chart above.

We’re Optimistic About Growth, But That Means Higher for Longer

We acknowledge that the neutral rate can’t really be known until we get feedback from the economy and markets in real time, but part of our job is to establish a baseline view. As a rough estimate, we believe a nominal fed funds rate of around 3.5% with a mild bias to the upside would probably be neutral in the current environment. That’s a full percentage point higher than the Fed’s estimate.

Roughly speaking, we can break down this difference into three pieces. The main piece is that we think we may be entering an extended stage of above-trend productivity growth that can improve the overall growth trajectory. That can account for about 0.5% of the 1% difference.

Add to that some expectation that inflation overall will still be fairly low but may be somewhat more volatile given higher growth expectations and could also run a little hotter than recent history given some structural changes in the global economy such as higher global labor costs, trade policy, and increased “home sourcing.” While it largely went unrecognized on Main Street, low inflation was one of the great boons of free trade. More restrictive trade, even if out of both fairness and necessity, will lower the impact. Make that about another 0.25% of our adjustment versus the Fed’s neutral rate.

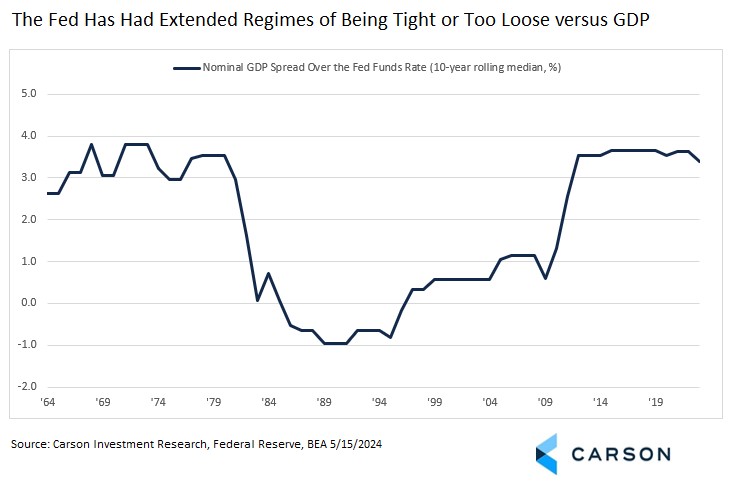

Finally, there’s the Fed’s tendency to have extended regimes in which Fed policy tends to be too loose. Although the Fed is an effective body overall, there will always be some bias toward emphasizing full employment over low and stable inflation in its dual mandate. As you can see in the table below, the fed funds rate has tended to run a full 3% under nominal GDP over two extended periods. Based on the spread between modeled r* and potential GDP, all else equal that should probably run something more like 1%. Let’s call the last 0.25% an adjustment due to the Fed’s tendency to run policy marginally too loose.

Investment Implications

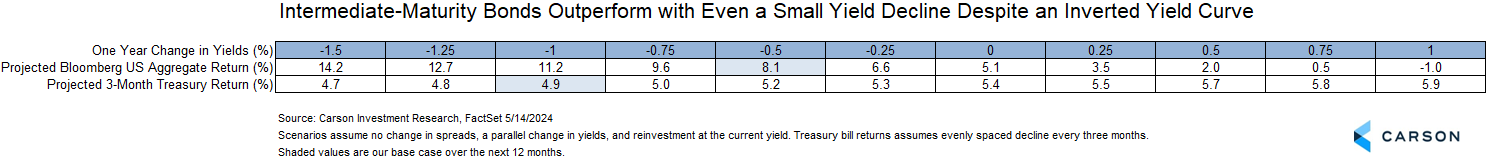

Even if 3.5% nominal is the center of gravity for the fed funds rate, it will take time for the Fed to get there. If growth remains on trend, the Fed will probably be biased toward lowering rates slowly. To be conservative, let’s say four cuts over the next year. As discussed in an earlier blog, the 10-year Treasury yield tends to decline at about half the rate of short-term yields in a rate cutting regime. Here is some simple scenario analysis of what that would mean for short-term bonds versus the Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index over the next year, with our baseline outcome highlighted.

There’s an important meaningful takeaway from all this from a portfolio perspective. While the potential return advantage of intermediate bonds over short-term bonds looks brighter, as long as rates remain high, bonds’ traditional role as a portfolio diversifier is likely to remain less robust. Because of that we’re comfortable being positioned in intermediate-term bonds, especially since we are recommending an underweight to bonds to begin with. But we do continue to see the value of non-bond diversifiers and are actively deploying modest allocations in both our tactical and strategic allocation recommendations.

For more content by Barry Gilbert, VP, Asset Allocation Strategist click here.

02240895-0524-A